African Countries’ Bond Rush: A Return To ‘Original Sin?’

The hunt for yield driven by low returns on many Western sovereign bonds, as well as those of the more established emerging markets, has led to a growing appetite by foreign investors for African debt.

However, many fear that the wave of international bond sales by African countries and other poorer developing states might be a signal that some of these countries are returning to a period of what economists call “the original sin,” characterized by excessive borrowing in foreign currencies.

The phrase was developed to describe situations in which a country borrows in another nation's currency, which can contribute to and worsen financial crises. When faced with a crisis, a country’s local currency falls, and the cost of servicing and repaying the international debt becomes higher, leading to default and possibly a deeper crisis.

This was none more so the case than in Zambia in the early 2000s, which resulted in the World Bank having to cancel up to $3 billion in external debt in 2006.

While the concern that African governments may again be overstretching themselves is understandable, Shilan Shah, Africa economist for Capital Economics, believes these fears appear to be premature -- for the time being at least.

“External debt levels are far lower now than they were 10 years ago,” Shah wrote in a note to clients. “What’s more, there is evidence that borrowing is now being used to invest in infrastructure, which can help to boost long-run growth and, in turn, support higher levels of debt.”

Following Zambia’s wildly successful launch of its debut 10-year eurobond in September 2012, which saw 24 times more demand than government sought to raise, now others want in.

Zambia Railways Ltd., the state-owned operator, said this month it plans to sell a $500 million bond, according to Bloomberg, joining at least three other government companies and municipalities (the Roads Development Agency, Zesco Ltd. and the Lusaka City Council) issuing more than $4 billion in debt this year.

Nigeria, Angola and Ghana plan to sell as much as $3.75 billion in international bonds this year, the most from the continent ever.

Nigeria is looking at issuing a eurobond worth up to $1 billion to fund its power and gas sector reforms, while Angola is seeking $2 billion of debt. Ghana, which issued the first eurobonds in sub-Saharan Africa outside of South Africa in 2007, may sell a further $750 million.

The World Bank estimates that sub-Saharan Africa needs $93 billion a year to overcome poor road networks and shortages of power and water.

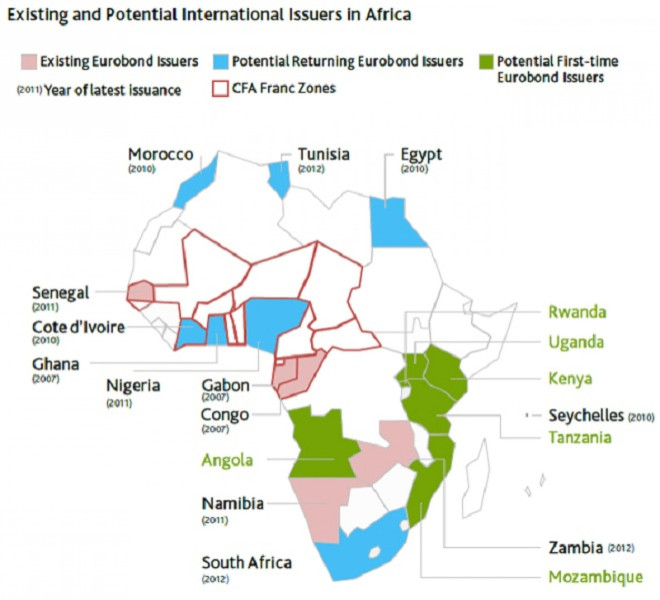

According to a Moody’s report, only 13 out of 54 countries in Africa have issued foreign currency-denominated instruments on the international markets. Ten of these are in sub-Saharan Africa.

Moody’s identified six countries in sub-Saharan Africa “that we believe will issue inaugural bonds on the international markets within the next few years.” (Those six nations are indicated on the map below in green.)

Shah of Capital Economics pointed to a number of reasons why countries are planning to issue foreign-currency debt.

At the moment, the biggest source of finance for African countries is from multilateral institutions (such as the IMF) or aid flows. But these forms of funding tend to have conditions attached, which limit the ability of a country to act independently.

By contrast, bond issuances come with few conditions attached, allowing governments to channel funds into areas that it sees as priorities.

In addition to this, borrowing in a foreign currency is attractive as yields tend to be far lower than on a local currency. For instance, Ghana’s 10-year international bond is currently yielding around 4.5 percent, while a five-year local bond yields more 20 percent.

While some analysts fear that the temptation of record-low borrowing costs could eventually lead to new debt crises, Shah thinks the fears are overblown.

The overall level of external debt is far lower now than was the case in the run-up to the World Bank’s debt cancellation program. In the early 2000s, Zambian external debt was hit 180 percent of gross domestic product. But even after accounting for its $750 million eurobond issue last year, external debt is now only around 25 percent of GDP. This is roughly the same level as 2006 when the debt cancellation program was completed.

More importantly, what matters is how borrowed funds are being used.

“Previously, funds have been used to plug a gap in current spending," Shah said. "But now, they are primarily being used to finance investment in infrastructure. ... Investment levels across the region are rising and are higher now than they were in 2000.”

On Wednesday, Fitch Ratings said growth in sub-Saharan Africa through this year is expected to remain above 5 percent, supported by infrastructure spending, development of mineral resources and growing consumption.

This will make it the second fastest-growing emerging market region after Asia.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.