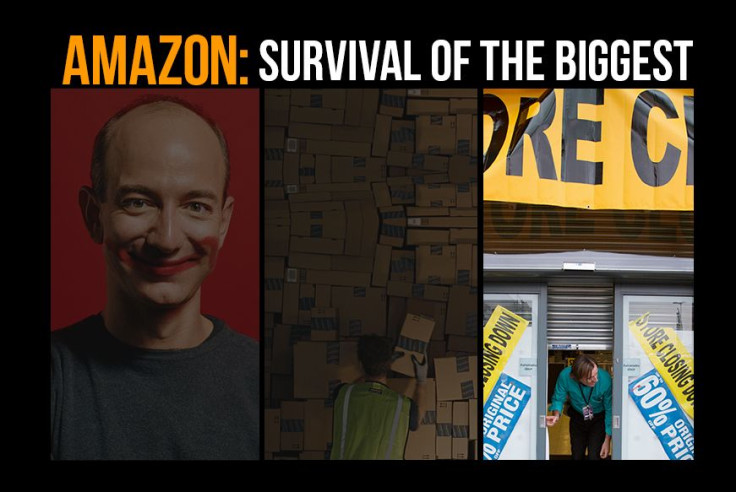

Amazon.com And Retail: Predatory Pricing, Bully Tactics Squeezing Competition, Retailers And Small-Business Advocates Say

This is the third of a three-part series exploring Amazon’s business model. On Wednesday, we examined the company's lack of profitability relative to its revenue growth. On Thursday, we probed the company’s labor practices. Today, we look at the company's impact on small retailers.

Michael Rosenberg clearly remembers the most popular item at Granny-Made, the funky children’s shop on Manhattan’s Upper West Side that he owned and operated for 27 years until it closed this summer. It was a deluxe toy garage, three levels high, complete with a carwash, moving scrubbers and even a rescue helicopter. “Every kid who came in played with that garage,” Rosenberg recalled, his cheery voice brimming with nostalgia.

Yet while preschoolers loved it, parents didn’t -- particularly the $139 price tag. Some said they needed more time to think about it. Others promised they’d be back after lunch, only they never came back. And the garage never sold. Rosenberg knew exactly what those customers were up to. “I couldn’t compete with Amazon,” he said. “They’re selling it so close to cost, and with free shipping, that I can’t compete against that.”

That same toy garage is currently selling for $69.99 on Amazon.com Inc. (NASDAQ:AMZN), the world’s largest online retailer and one of the fastest-growing companies in Internet history. Since its nascent days as a bookselling startup to its current position as a multinational behemoth with $61 billion in sales last year, Amazon has seduced consumers with its promise of low prices and convenience, but at what cost? What are the implications of Amazon’s emergent dominance over the retail industry? Or to put it another way, what happens when we put all of our eggs in one virtual shopping cart?

The problem with questions like this, consumer experts say, is that few people think to ask them, especially regarding to Amazon. While Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (NYSE:WMT) seems to meet with fierce protests and Twitter fury at nearly every new store opening, Amazon’s activities course through the Internet amid little backlash, at least not from its customers. This despite the fact that, by some estimates, Amazon now generates more online sales than its 12 largest competitors combined.

“They’ve really flown under the radar in terms of there being a public conversation about their power within the marketplace and what the implications of that are,” said Stacy Mitchell, a senior researcher for the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, who has been studying Amazon’s effect on the retail industry and local economies. “People haven’t really thought about this company in the same way that they have other retailers like Walmart. Amazon’s operations are invisible. All you really see is the website, and then when you open your door, the Fed-Ex guy is there.”

One-Click Collateral Damage

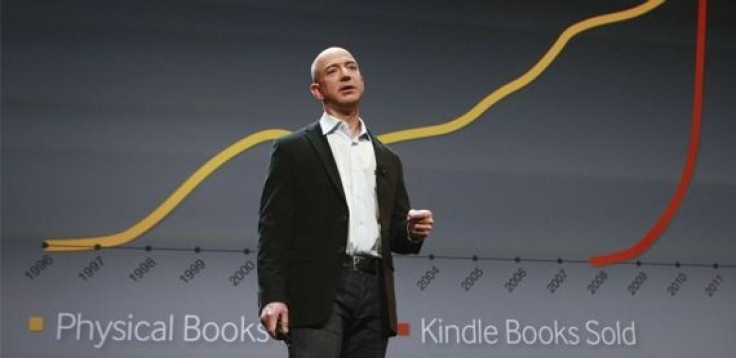

So what’s happening between Amazon’s website and the Fed-Ex guy? It turns out, quite a lot. By now almost everyone knows about the loss of physical bookstores, buckling under the weight of Amazon’s lowball prices and the ubiquity of its Kindle e-reader. In a rare interview with CBS’ “60 Minutes” earlier this month, Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and chief executive, downplayed his company’s role in that trend. It’s “the future” that’s killing bookstores, he said with an awkward smile. Not Amazon. “People can complain about that, but complaining is not a strategy,” he told the network.

You might think such a cavalier attitude makes Bezos sound like the alien from “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” who blew up the Earth to make way for an intergalactic highway. You wouldn’t be alone. The intensity with which Amazon is loved by its customers is matched only by the anxiety and animosity of its competitors. And bookstores are only the beginning. International Business Times spoke with struggling retailers of every shape and size, from across the United States, Canada and Europe. They have either lost the fight against Amazon’s ascendency or are fighting tooth-and-nail not to.

And despite Bezos’ dismissive brush-off, the proprietors of these fading or former establishments aren't out-of-touch dinosaurs who have failed to adapt to a digital world. They are versatile, shrewd entrepreneurs -- driven, and like most business owners, stubbornly competitive. But they are finding themselves increasingly walled off from a shopping ecosphere created and controlled by Amazon, on Amazon’s terms.

They are people like Rosenberg, whose Granny-Made shop successfully weathered nearly three decades of socioeconomic change in his Manhattan neighborhood before it closed this year. The shop survived the death of the mail-order catalog, 9/11, and Bloomberg-era gentrification. No matter what the challenge, Rosenberg said he was always able to adapt to changes in shopping habits. Even during the height of the Great Recession, in 2008, he didn’t lose hope. “We had a great following,” Rosenberg said. “There was every reason in the world for us to succeed.”

In the spring of 2013, when Rosenberg finally announced that he would have to close up shop, his longtime customers assumed it was another tale of a small business being priced out of Manhattan by soaring rents. It wasn’t. “I had an amazing landlord,” he said. “No, it wasn’t the rent. It was online shopping. It was showrooming.”

Showrooming, of course, refers to the now-standard practice of testing out an item in a brick-and-mortar shop only to purchase it for a cheaper price online. When Rosenberg explained to his customers that the practice was putting him out of business, he said the younger ones knew exactly what he was talking about. Some denied doing it, but he said he always knew the ones who did.

So did Rose Kriedemann, owner of Bayshore Hobbies, a hobby and game shop in Hamilton, Ontario, that closed its doors in July. A good-humored but feisty shop owner, Kriedemann would routinely confront customers who tinkered with the merchandise but never bought anything. Eventually they wore her down, and toward the end of the store’s 33-year run, she just put a sign in her window for anyone who moaned that they could get things cheaper on Amazon. It read: “F--- Off.”

“So whenever I had to hear about Amazon one more time, I’d say there’s the sign,” she said.

The Loyalty Fallacy

In a letter to Amazon’s shareholders in April, Bezos boasted, as he often does, that his company’s energy comes from a “desire to impress customers rather than the zeal to best competitors.” It’s a mantra we’ve heard so frequently that we barely question it. Amazon is building its market-share dominance by focusing on the customer. In turn, that builds loyalty. End of story.

Ironically, though, it’s Amazon’s own rise that most challenges that narrative. Customers love its prices and convenience, no doubt, but their willingness to flock to Amazon in lieu of the brick-and-mortar stores they patronized for decades has only proven that customer loyalty is more elusive than we think. In the final years of Granny-Made, Rosenberg said he began to question whether it exists at all. “What I noticed was that great following we had, and the loyalty, was really my older customers,” he said. “I think for the newer generation, it’s not that important.”

Kriedemann’s take is even more cynical. “There is no loyalty anymore,” she said. “It’s a change in people. If you go back 30, 40 years, people wanted you to succeed. Now they don’t. Maybe it’s because money is harder to come by these days.”

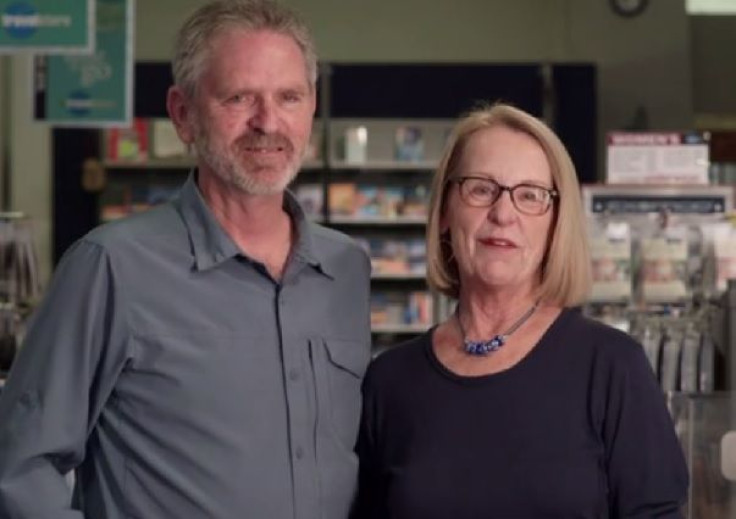

Bill Keller, owner of Le Travel Store in San Diego, agrees. Before his shop closed its doors for good this past June, he watched helplessly over the past few holiday seasons as customers would come in, play with travel bags, undo zippers and inspect compartments, only to walk out empty-handed. “Oh, sure, they love the local service,” he said. “They want to be able to handle the product. But if you can save 20 or 30 bucks on Amazon, you’ll come in and take that experience for free.”

Keller and his wife, Joan, opened Le Travel Store in 1976. It was a literal mom-and-pop shop, the first travel-accessories store in the country, he likes to say. Like Rosenberg and Kriedemann, the Kellers adapted and refined their strategy for decades as shopping habits demanded. They were early adopters of online commerce and had a thriving website business at LeTravelStore.com by 1997, before most of their competitors even had websites.

Keller said he believes customer service alone doesn’t account for Amazon’s dominance; rather, he feels it is something far more insidious. He cites, as a case in point, the company’s now-infamous price-comparison promotion during the Christmas shopping season of 2011. Amazon offered a $5 rebate to customers who scanned an item with its Price Check app while browsing in a brick-and-mortar store. Retail trade groups went ballistic, calling the move anticompetitive and underhanded. Price-comparison deals are nothing new in retail, but critics at the time pointed to the inescapable fact that Amazon was purposely exploiting the one asset -- and expense -- it didn’t have: a physical location. “It was pretty outrageous because it showed their predatory practices,” Keller said. “Everybody already knew what they were doing, but this made it blatantly clear.”

Amazon axed the promotion shortly after, but Keller said the damage was already done. The promotion, and the outcry that followed, popularized the concept of showrooming in the minds of consumers. At Le Travel Store, things were never the same. “It really got out of control that Christmas,” Keller said. “That’s when we started to see a lot of showrooming.” In other words, Amazon didn’t just passively benefit from this new shopping phenomenon; it was complicit in creating it. The secret was out, and Amazon leaked it.

The Search Is Over

While Amazon was busy disrupting shopping habits in the real world, its growth and increasingly diverse offerings were quietly causing even more disruption in the virtual one -- a shift that Keller said would be the final undoing for Le Travel Store. Throughout the 2000s, Keller recalls, his sales were aided enormously by Google searches for items like “luggage tags” or “money belts.” They were small-ticket items, but they would bring shoppers to the Kellers’ website and into their store. That all started to change in 2012, and quickly. Suddenly, Keller’s search traffic plummeted, and after doing a little research, he realized why. People were no longer looking for those items on Google. In fact, they weren’t using search engines at all. “People were going straight to Amazon,” Keller said.

His suspicions were backed up by at least one independent study. In July 2012, technology watchers Forrester Research released a report showing that 30 percent of online shoppers began their search at Amazon.com. In contrast, 13 percent began their search on Google. The trend marked a reversal from just a few years earlier, when Google Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOG) was what Forrester called the “dominant incumbent in shopping research.”

This change has put many competing retailers in a strange and admittedly humbling position. They can continue to fight a futile fight, or they can try to benefit from Amazon’s vast customer base by opening an Amazon seller’s account and selling their goods on Amazon.com. In exchange, the e-commerce behemoth gets a percentage of their sales and information on their customers’ purchasing habits to add to its vast trove of consumer data. In other words, buy it from Amazon or from a third-party on the site -- either way, Amazon wins.

“That was what we realized we needed to do,” Keller said. “We had to cough up to Amazon their share of our sales. They were destroying our business model, but that’s what we had to do if we wanted to stay in the game.”

Death Of Some Salesmen

Amazon derives about 40 percent of its sales from third-party sellers. These merchants aren't only reluctant competitors, like Keller, but also countless younger entrepreneurs who are building and maintaining their own businesses as Amazon merchants. And why shouldn’t they? Amazon makes a pretty good pitch, promising access to hundreds of millions of customers and the security of a trusted platform. But while asking retailers to build their livelihoods around its massive ecosphere, Amazon hasn’t exactly ensured a stable playing field nor does it seem interested in doing so.

Kasey Cox found this out the hard way. With her husband, Kevin, she is the owner of From My Shelf bookstore in Wellsboro, Pa. For almost four years, the Coxes sold books on Amazon.com, taking in on average about $1,500 a month. The income supplemented book sales for their brick-and-mortar store, while Amazon’s software helped manage their inventory, more than 10,000 books and other items.

It was all going swimmingly until one day in November 2008, when suddenly, and without warning, it was all gone. A form letter arrived in Kasey Cox’s inbox at 2:04 a.m. explaining that their seller’s account had been closed, permanently, with no option to appeal the decision. If they tried to open another account, they were told, that one would be summarily closed as well. “We thought it was a joke at first,” Cox recalled. “It was just so shocking and bizarre and completely out of the blue.”

The letter offered little clue as to why, only a vague explanation that the Coxes had engaged in “inappropriate contact with other Amazon.com participants.” Cox, whose voice still trembles when she talks about the experience, said she had no idea what “inappropriate contact” means and was never able to find out. She said emails pleading with Amazon for more information were fruitless. The only phone number she could find for the company was a customer-service line that led nowhere.

As many a member of the media can tell you, Amazon’s propensity for one-sided conversations is notorious. It rarely responds to press requests (we sent an obligatory one for this article; no answer), outside of an automatic email acknowledging that it received them. As a seller who had depended on Amazon, Cox faced a similar brick wall. She said the sudden shuttering of her seller’s account -- which meant the loss of income and access to her inventory database -- nearly put her bookstore out of business, and it was only through being “stubborn as hell” that she and her husband were able to survive. “It happened right before textbook season and Christmas, and that was devastating to us,” she said. She also claims to have heard similar stories from other booksellers, and said it felt “very validating” to learn that she wasn’t alone. “Sometimes misery loves company,” Cox added.

In fact, she has a lot of company. In March 2013, a class-action lawsuit was filed on behalf of Amazon sellers who claim that Amazon unlawfully withheld their payments as it conducted “investigations” into their accounts, and in some cases closed them without explanation. Buried deep within Amazon’s merchant agreement is a clause that allows Amazon to hold sellers’ funds at its “sole digression,” which lawyers argue violates laws that govern fiduciary agreements. The lawsuit also says that Amazon has -- no surprise here -- “simply ignored” the plaintiffs’ attempts to resolve the situation. It seems that customer-centric ethos that Bezos likes to trumpet doesn’t extend to Amazon sellers.

The Internet is filled with stories of Amazon sellers waking up to find their accounts unexpectedly closed. Many, like Cox, say it happened right before the holidays, and some are too tired of fighting to say any more. “After three months of anger and stress I gave up and let it go,” one bookseller, whose account was closed in early December 2012, told IBTimes.

Is it all the result of an arbitrary algorithm sending up red flags -- perhaps incorrectly -- or is it something more calculated? Cox doesn’t think the timing of the closures around Christmas when every retailer -- even Amazon -- would prefer fewer competitors for the huge demand from motivated consumers is coincidence. Nor does she discount the fact that she and her husband heretically opened a brick-and-mortar bookstore a year after becoming Amazon sellers. “I think that has everything to do with it,” she said emphatically. “I’m not a conspiracy-theory person, but that seems pretty clear to me.”

The Future Is 20 Years Ago

In September 1995, Amazon’s hometown newspaper, the Seattle Times, wrote an article about the quaint “virtual bookstore” that had just launched two months earlier. In the piece, a 31-year-old Bezos said he believed the time was right for online retail. The nascent World Wide Web was growing, and enough people finally had access to it to make virtual bookselling a viable business. He had the foresight to grasp this before most people knew what the Web was.

At the time, his competitors in the brick-and-mortar world didn’t see the scrappy new startup as much of a threat. “I don’t think you’ll ever be able to substitute coming in and looking through the book that you want,” Kristin Kennell, the night manager of Elliott Bay Book Company, told the Seattle Times. And why shouldn’t she scoff? Elliott Bay was the biggest bookstore in Seattle and a local landmark. It had built up decades of customer loyalty. (Remember customer loyalty?) And yet less than three years after the Seattle Times piece, Elliott Bay’s owner, Walter Carr, sold the bookstore. In an interview with the same newspaper in 1999, he said he had been stripped of the joys of entrepreneurship. Changes in the book business “have been personally defeating to me,” he admitted.

Amazon is the 11th largest retailer in the United States, according to the National Retail Federation. Its U.S. sales grew by an astounding 30 percent last year, and at the rate of current growth, it could outpace Walmart to become the largest retailer by the end of the decade. It is acquiring competitors at a frantic pace. It gobbled up the New Jersey-based Quidsi Inc., owner of Diapers.com, Wag.com, YoYo.com and Soap.com. It owns Woot Inc., Bop LLC, and the shoe-selling giant Zappos IP Inc. Even if you’re not shopping online with Amazon, there’s a good chance you’re shopping online with Amazon.

Does it matter? Not everyone thinks it does, even among those who have the biggest reason to curse Amazon’s existence. “I roll my eyes when I read articles about how Amazon is taking over everything,” Michael Powell, owner of the storied Powell’s Books in Portland, Ore., said. “We’re doing fine.”

One German manufacturer, who is seeking a deal to sell his products on Amazon, scoffed at the notion that Amazon could one day be the last online retailer standing. It’s an implausible scenario, he said, from a “country far, far away.” That same manufacturer asked not to be named in this article for fear of portraying Amazon in a negative light. “If not necessary I would not wake a sleeping dog,” the manufacturer said.

Every year in his annual report to shareholders, Bezos attaches his original shareholder letter from 1997, the year Amazon first went public. Then, as now, Amazon’s founder was fond of saying that we're still in “Day One” of the Internet, and it’s hard to argue that we’re not. But for those companies struggling to compete with this new kind of superstore, Day One feels like the End of Days. They, too, see “the future,” the one that Bezos has blamed for killing them off. They see a world where storefronts are obsolete and economies are stimulated not by local merchants with a personal stake in where they do business but by a select few online players. It can be a depressing prospect if you care about things like civic engagement, livability and social capital, all of which tend to decline with the disappearance of local businesses.

At the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, an optimistic Mitchell insists that accepting the inevitability of digital commerce doesn’t have to amount to a Faustian bargain. “It shouldn’t be a dichotomy between online shopping and all these other values,” she said. “It’s possible to be able to have a world where you can take advantage of the convenience of online shopping and still have a healthy local business community. That’s a huge thing that’s at stake in the future.”

Got a news tip? Email me. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.