Are Streetcars In NYC Too Ambitious? De Blasio’s New York City Light Rail Would Connect Brooklyn, Queens

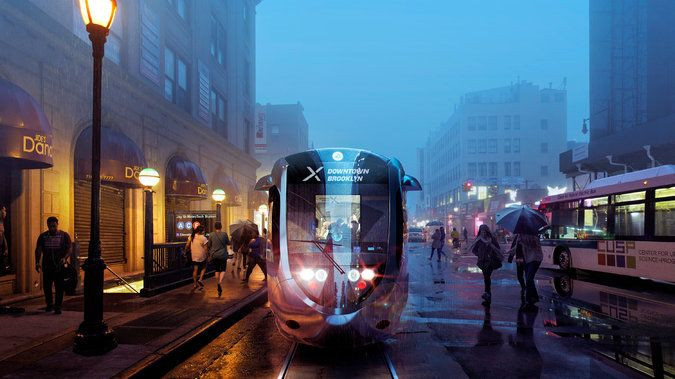

Most New Yorkers regard streetcars as a relic of New York City's past, but a new proposal expected to be announced Thursday night for a ground-level rail system that would run along the East River waterfront in Brooklyn and Queens aims to propel — and expand — the city’s mass transit system into the future.

The cutting-edge light rail project may seem lofty as it attempts to reach under-serviced corners of the city, but urban planning and transit experts counter that it could be a success, despite all of the opportunity for service interruption during the lengthy 16-mile route in one of the most populated cities in the world.

The project, proposed by Mayor Bill de Blasio, would follow the likes of other American cities, such as San Diego, California, and Portland, Oregon, which have seen increased commuter traffic since their systems’ implementation.

“Thousands of new residents are moving to that area and having a hard time when it comes to access to mass transportation,” said New York City Councilman Ydanis Rodriguez, a Democrat serving the Washington Heights and Inwood neighborhoods of upper Manhattan who chairs the council's transportation committee. “I am happy the mayor is working on this and he will no doubt leave a great legacy.”

Yes to The Brooklyn Queens Connector (BQX)!! https://t.co/qsP81TtwjD __ #tech #startup #entrepreneur pic.twitter.com/tNg0TYVdPO

— NYU Entrepreneur (@NYUEntrepreneur) February 4, 2016

Through its route along the East River, the streetcar system would link Sunset Park, Brooklyn, to Astoria, Queens, a stretch that lacks the same convenient rapid transit options that other parts of the city boast.

“It would revive more of the waterfront for residential and commercial developments” said Georges Jacquemart, a principal at urban development agency BFJ Planning in New York City. “Along the waterfront there are some tourist attractions, there are parks and the ferry service and more and more people are interested in the area.”

If all goes according to plan, property taxes in the area would skyrocket and could cover the light rail’s $2.5 billion estimated price tag, according to Jacquemart. “The increased value of those properties by the stops would then be used to repay the street car,” he said. “It’s definitely a good financing mechanism.”

Such expectations came to fruition in Portland where the first modern streetcar line in the country was launched in 2001, creating more than $4.5 billion in market value in the corridor where the system was built, according to local transportation officials. All the while, daily ridership increased from 4,000 to 15,000 commuters daily as of July 2015.

“It has done wonders for the neighbors that it's connected, prompting new development and real estate developers to build to their full capacity," said Dylan Rivera, spokesman Portland Bureau of Transportation. “We found that developers have built to the maximum density of the code the closer they are to a streetcar stop.”

The Northwestern city opted for the sleek streetcar system, instead of buses, because of the benefits infrastructure provides. “The tracks are a visible investment in providing a service to that neighborhood and developers love that because that means for the next 50 years, this streetcar is likely to serve that neighborhood,” Rivera said. “These specific intersections with a museum stop or a stadium stop allows the area to take on an identity and that adds buzz to that location.”

When compared with other forms of transportation, urban planning experts said streetcars are one of the more cost effective options for New York City, even if it exceeds its projected $2.5 billion. They point to the city’s undertaking to redesign the Second Avenue subway that broke ground in 2007. Building the first of its four phases has cost $4.5 billion and turned into an epic construction project, but it will serve a portion of the city that is all but isolated from the nearest subway station. Phase one is expected to be completed in December.

“Subways are extraordinarily expensive,” said Daniel Chatman, an associate professor of city and regional planning at the University of California at Berkeley. “Look how long it took to do the Second Avenue subway. So unless they’re flushed with money and everyone thinks that the right thing to do, then it’s not [the right decision for New York City].”

It’s also difficult to correctly predict how much a subway construction project would run, according to Chatman. “When it’s underground, you don’t know what’s there. When you’re on the surface there’s a lot more that’s known. Nevertheless I’d expect [the $2.5 billion] to be an underestimate of the final cost.”

Chatman said the proposed project is definitely feasible and will likely see increasing ridership for years upon completion, but that doesn't mean there won’t be bumps in the road, both politically and literally when it begins service on the 16-mile route. “If there is any bottleneck anywhere, it could really dampen the line as a whole,” Chatman said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.