Mysterious Copiale Cipher Code Finally Cracked by Computer Scientists

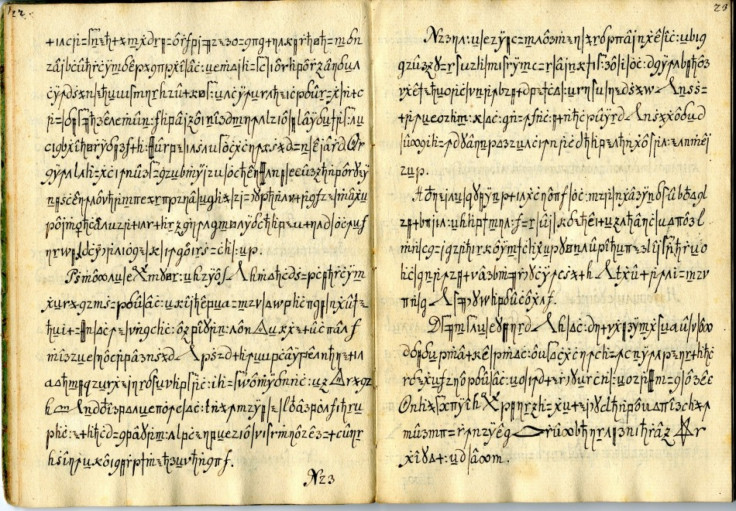

The Copiale Cipher could be something out of a Dan Brown novel or a 21st-century update on the Indiana Jones story arc. A yellowing 18th-century manuscript consisting of a mystifying mix of alien symbols and Greek and Roman letters, the Copiale Cipher has been confounding cryptographers since its discovery in the archives of a university in the former East Germany immediately following the Cold War.

That is, until Kevin Knight, a computer scientist at the Information Sciences Institute at the University of Southern California and expert in natural language processing, and two colleagues from Uppsala University, Beáta Megyesi and Christiane Schaefer, decided to take a crack at the cipher.

The 105-page document contains 75,000 characters, all of which are encrypted except those that make up two items: the name "Philipp 1866" appears on the flyleaf, while "Copiales 3," the origin of the manuscript's moniker, is inscribed as a note on the last page.

"I don't have much experience in cryptography," said Knight in an interview. "My background is primarily in computational linguistics and machine translation."

The team of experts, none of whose expertise was in cryptography but rather in the computer sciences and linguistics, leaned on statistics-based translation techniques, not unlike those behind the popular online tool Google Translate.

Initially, the researchers thought the Roman and Greek characters sprinkled throughout the text might themselves make up the code. Yet, after fruitless attempts in eighty different languages, the team still had found nothing of value in the familiar letters.

Taking a different tactic, the team then began isolating the letters, treating them as "nulls," or red herrings planted to misdirect would-be decipherers - ultimately, they would prove to be the spaces between the words in the code. Concentrating on the symbols, which constituted most of the 'text,' they eventually tested the theory that symbols with similar shapes represented the same letter or same groups of letters and scored a hit.

The first words that emerged from the German translated to "Ceremony of Initiation," followed by "Secret Section." The team has so far translated about sixteen of the 105 pages of the document and discovered that it contains the rituals of a secret society interested in the subjects of eye surgery and ophthalmology.

As it happens, the Copiale Cipher was reveals the rites and tenets of an 18th-century secret society in Germany whose members were obsessed with eye surgery and ophthalmology. The text outlines bizarre rituals - including one involving the plucking of eyebrows - but also proclaims the group's manifesto and doctrine of beliefs, including the nature of man as a free being.

"This opens up a window for people who study the history of ideas and the history of secret societies," says Knight. "This is very interesting to historians because they can start to date the development of political ideas."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.