Quadriplegic Man Regains Some Use Of Hands After Doctors ?Rewire? His Nerves

A 71-year-old quadriplegic man has regained some use of his hands thanks to surgeons at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Doctors rewired the man, rerouting working nerves from his upper arms that were still able to communicate with his brain.

After a year of physical therapy, the man can now bend his thumb and index finger -- enabling him to feed himself bites of food and write with assistance, according to a report published on Tuesday in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

This is not a particularly expensive or overly complex surgery, lead author Susan E. Mackinnon said in a statement on Tuesday. It's not a hand or a face transplant, for example. It's something we would like other surgeons around the country to do.

Ida Fox, an assistant professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Washington University, says moving nerves around is a bit like robbing Peter to pay Paul -- or in this case, robbing the elbow to pay the hand.

There is a bit of trade-off, Fox says. Luckily we have some spare parts.

Nerve transfer is already frequently used for peripheral nerve injuries, which are more common than you might think.

Fox has shuffled nerves around to give hands back to gunshot victims, stabbing victims and others. Most of her patients, she says, are young men who decide to punch plate glass windows. One of her other patients fell on a windowpane while repairing his Victorian house and severed the ulnar nerve that runs from the ring and pinky fingers to the shoulder.

But spinal injury cases often present a more challenging obstacle.

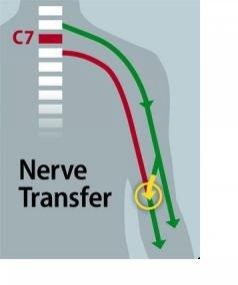

Nerve transfer was able to work for the patient described in the Journal of Neurosurgery paper because his injury -- caused by a car accident -- was localized to the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae at the bottom of his neck. The accident paralyzed him from the waist down, and he lost the ability to flex and extend his fingers.

While the nerves springing from the patient's damaged vertebrae couldn't communicate with the brain, the nerves originating in the spinal cord above the injury site could still talk to the brain.

Mackinnon and her colleague selected one of these nerves -- the brachialis nerve, located in the upper arm and connected to one of two muscles that work to flex the elbow -- as a donor. They connected it to the patient's nonworking anterior interosseous nerve, which activates the muscles that flex the thumb and index finger.

Once the patient's arms were sewn back up, that wasn't the end, though. He still had to retrain his brain to remember that the motion that previously would have flexed his elbow now flexed his thumb.

In this particular procedure, the brain remodeling process is somewhat intuitive, Fox says, given the related motions of the elbow and the hand.

You're using a muscle that makes sense. When you bring food up to your mouth you're generally bending your elbow and pinching at the same time, Fox says.

One of the alternative methods for restoring hand function after an injury is tendon transfer, where a muscle is moved by detaching a tendon and sewing it into a different place. This kind of procedure is a blunt instrument, according to Fox, because you're taking one of the muscles that move the elbow and asking it to perform a different task.

Nerve transfer, she says, results in a relatively finer degree of control for the patient.

Fox hopes that the procedure will encourage more hand surgeons to become more familiar with paralyzed patients. Currently, many hand surgeons are reluctant to work on these kinds of cases, she says.

A lot of us don't have contact with these types of patients. The quadriplegic patient population is one that we as physicians don't treat very well or serve very well, Fox says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.