Human Microbiome Project: Researchers Take A Tiny Census

The poet John Donne once remarked that no man is an island. Scientists investigating the teeming hordes of bacteria living in the human body are finding out that Donne was only partially right - man is more like a continent.

This week, the first results are in from the Human Microbiome Project, which is investigating the bacteria that outnumber human cells in our bodies 10 to 1. Some of these microbes, it turns out, might be key to our survival.

In 14 research papers appearing Wednesday - some in the journal Nature and others in publications from the open-access Public Library of Science - researchers from nearly 80 institutions related their findings from this micro-census.

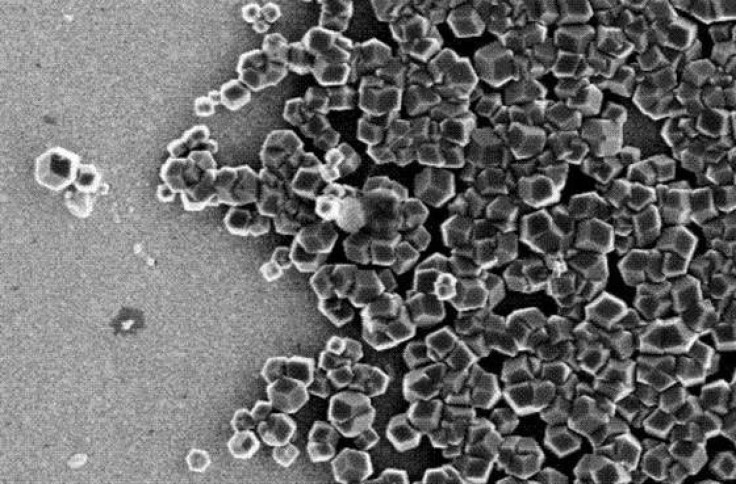

To gauge the diversity of species in the human microbiome, HMP researchers took samples from 242 healthy volunteers, focusing on different body sites - mouth, nose, the skin of the inner elbow, stool, genitals. Where before, scientists could only characterize a few hundred bacterial species that live inside humans, the HMP project now estimates that there are more than 10,000 species hitching a ride on and inside people.

Many of these bacteria are benign freeloaders, neither benefiting nor harming the host, but some are actively helping out.

Humans don't have all the enzymes we need to digest our own diet, Lita Proctor of the National Institutes of Health and HMP program manager said in a statement Wednesday. Microbes in the gut breakdown much of the proteins, lipids and carbohydrates in our diet into nutrients that we can then absorb.

Microbes also produce beneficial things like vitamins and compounds that suppress inflammation in the gut that humans are incapable of producing, according to Proctor.

They found that each person is a patchwork of dramatically different microbial ecosystems, and each individual can be a completely different landscape from someone else. Thus, it's hard to characterize any kind of common core human microbiome (the overall bacterial constitution) according to UNC Charlotte researcher Anthony Fodor, a co-author of a paper appearing in PLoS ONE.

While Fodor and his colleagues found that while the community of bacteria living in the mouth was fairly similar from person to person, that wasn't true for other parts of the body.

In one stool sample, a certain type of bacteria might account for 90% of the gene sequences that the team found. But in another person's stool, that same bacteria might represent just .01% of the genetic material.

This kind of variation is not just true of this type of bacteria but of essentially every type of bacteria within the HMP, Fodor said in a statement Wednesday.

Francis Collins, the Director of the National Institutes of Health, compared the project to the mapping of a strange new continent.

This lays the foundation for accelerating infectious disease research previously impossible, Collins said in a statement Wednesday.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.