Asexual Fungus Love Cleans The Water, Researchers Find

A fungus that makes its home in polluted water is actually helping to clean up the environment as it reproduces asexually, according to new research.

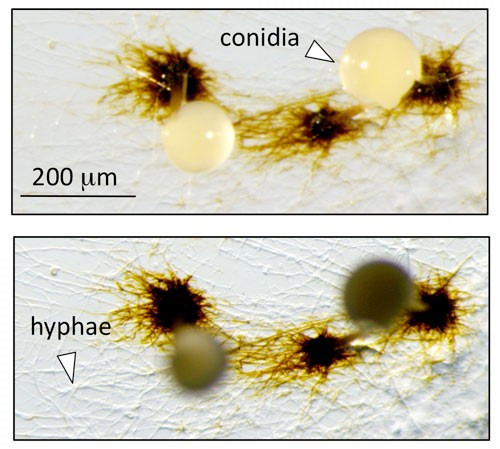

In a paper published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team led by Harvard University scientists describe how the fungus in question, Stilbella aciculosa, makes a chemical called superoxide when it produces spores. Superoxide can react with the element manganese, converting one form of it known as Mn (II) to a different form, Mn(III) or Mn(IV).

If you can get manganese to oxidize, then it forms these really active minerals, manganese oxides, which are environmental sponges that will clean up the water, Harvard researcher Colleen Hansel explained in a statement on Monday.

People already use bacteria and fungi as part of efforts to clean up coal mine drainage, but it frequently doesn't work. Existing approaches involve introducing lots of nutrients -- in this case, corn cobs and straw -- into the water for microbes to feed on, but that might not be necessary, according to the new research.

The researchers still aren't quite sure why the fungus makes the superoxide.

It looks like an accidental side reaction, but we don't really know, because manganese oxides are very reactive and could therefore provide some indirect benefits to the organism, Hansel says.

The manganese oxides created by superoxide could possibly be degrading carbon sources in a way that makes them easier for the fungus to feed upon, she speculated.

We're traveling down a whole new avenue in biogeochemistry, says Hansel. It's exciting right now to be one of the people sitting in the front seat.

SOURCE: Hansel et al. Mn(II) oxidation by an ascomycete fungus is linked to superoxide production during asexual reproduction. PNAS published online before print 16 July 2012.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.