Australia Rebalancing Its Economy Amid China Slowdown

The China resources boom is over, leaving Australia with no other option but to rebalance its economy. If the commodity-rich country does it right, economists say Australia could orchestrate the first soft landing from a mining boom in the country’s history.

“Mining investment is now falling, after a substantial ramp-up in recent years … but low interest rates are supporting a rise in housing prices, residential construction and consumer spending, which is rebalancing growth,” HSBC Chief Economist Paul Bloxham said.

China’s investment boom has been the key driver of stronger demand for copper, iron ore and steel over the past decade. As a result, the first set of economies affected by a dramatic slowdown would be big commodity producers that sell to China or rely on its demand indirectly.

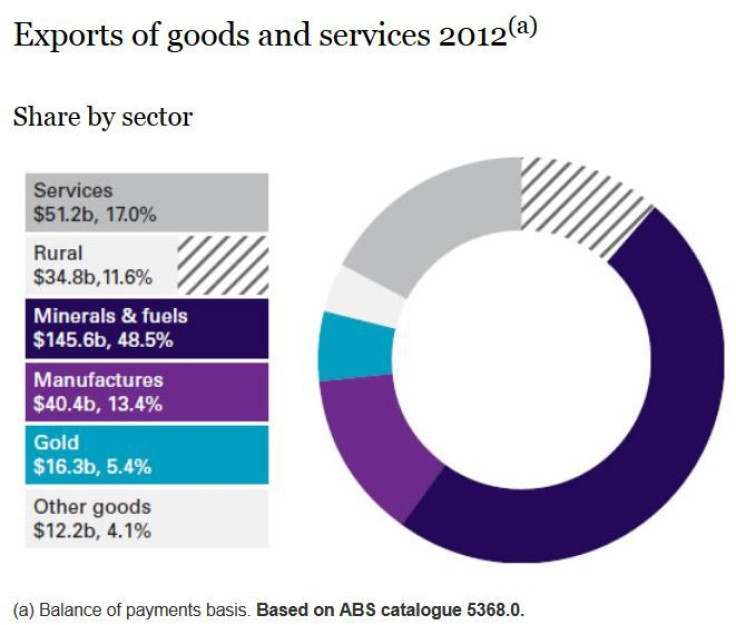

Australia, which dispatches more than a quarter of its exports to China, has already felt the pain. As former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd recently said, his country now faces the end of a decade-long resources boom in which China represents 10 percent of GDP.

Australia’s resources industry accounts for almost 10 percent of the nation’s job market -- about double the level of a decade ago -- and close to 20 percent of national output, with coal and iron ore among the country’s largest exports. “If we make the wrong decisions now, we will be living with those decisions for the decade ahead,” Rudd said.

The good news is that early signs of economic growth rebalancing were already apparent in last year’s fourth quarter gross domestic product numbers.

Overall GDP growth picked up in the last three months of 2013, with household spending as a key driver. Mining investment fell as fewer new projects got started and some of the larger projects that were under construction were completed.

“The period when the mining sector significantly outperforms the rest of the economy is likely to be over, but we expect mining GDP to slow down, not collapse,” Bloxham said.

Why Australia Won’t Land Hard

Australia will be able to navigate the turbulent waters without hitting an iceberg for several reasons, according to Bloxham.

First, he pointed out that unlike previous mining booms, this boom has not seen high inflation, a wages breakout or a large blowout in the current account. Rather than overheat the economy, the expansion of the mining sector saw other sectors of the economy crowded out to make way for the boom.

Second, the investment that has been made was largely an appropriate allocation of capital.

Third, the Australian economy will likely be cushioned by the high import share of investment. Historical analysis by the Reserve Bank of Australia has shown that mining investment tends to be approximately half-imported.

The assumption that half of all capital imports have been for mining suggests that instead of mining investment boosting the economy by approximately 2 percentage points of GDP a year in 2011 and 2012, it probably boosted the domestic economy by closer to 1 percentage point each year.

Hence, the estimated 2 percent to 3 percent of GDP decline in mining investment that is expected over the next two years may turn out to have only half of that direct effect on the domestic economy, according to Bloxham.

Fourth, the fall in mining investment that is expected in 2014 and 2015 is likely to be more than offset by a rise in exports, with strong export growth expected in coming years.

Finally, despite commodity prices having fallen from their 2011 peaks, they are still at high levels relative to history, which is expected to support the profitability of Australia's mining production.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.