Big Pharma's Unlikely Allies: Labor Unions Support Strong Intellectual Property Provisions In Trans-Pacific Partnership

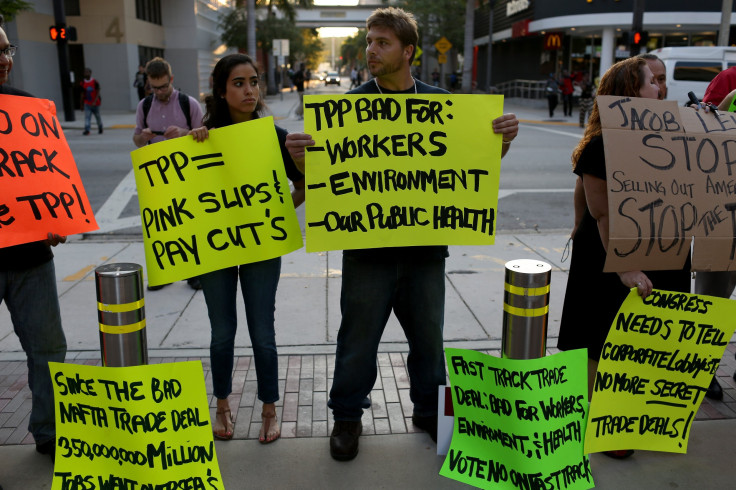

When the top pharmaceutical lobby in the U.S. sponsored a Twitter chat on the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in March of last year, labor unions trolled it hard.

The Communications Workers of America posted:

#TPP = massive handout 2 Big PhRMA, enriching corps by raising costs & reducing access 2 life-saving meds. http://t.co/Q3HR84R1NW #ProChat

— CWA (@CWAUnion) March 21, 2014And the International Brotherhood of Teamsters tweeted:

PhRMA is paying for this because they want TPP to extend patent monopolies, raise med prices. #ProChat #Politicorp #TPP

— Teamsters (@Teamsters) March 21, 2014But not all unions are as repulsed by Big Pharma’s lobbying on trade. Some even support it.

Seven different unions -- the Boilermakers, Electrical Workers, Fire Fighters, Iron Workers, Plumbers and Sheet Metal Workers, as well as the International Union of Police Associations -- are united with the nation’s biggest drug companies in an alliance that’s spent almost $1 million lobbying Congress on intellectual-property rights, which would be covered by the proposed TPP.

The unions are members of the Pharmaceutical Industry Labor Management Association (Pilma), a coalition including the powerful Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) and major drug companies such as Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer Inc. Since May 2009, Pilma has doled out $720,000 lobbying Congress for “patent protection regulations within trade agreements,” in addition to $342,500 on TPP and other issues such as Medicare Part D, according to a review of lobbying-disclosure forms by International Business Times.

Pilma Executive Director Tim Dickson, a lobbyist whose firm Groundswell Communications Inc. is based in Alexandria, Virginia, insists Pilma has no official position on either TPP or fast-track negotiating authority: The management side of the alliance supports both, and the labor side opposes them. That hasn’t stopped Pilma from lobbying on intellectual-property issues within the scope of the trade deal, including, most prominently, support for a 12-year window on what’s known as “data exclusivity” for biologics products -- a period during which government regulators cannot share or publicly release test data on the safety and efficacy of new drugs. Biologics are widely regarded as the cutting edge of medicine, and can be used to treat cancer and autoimmune disorders.

That 12-year period for biologics is already in place in the U.S., but no international standard exists, and it’s never been part of a trade agreement before. Public-health advocates like Doctors Without Borders oppose such provisions within TPP, since they would effectively delay cheaper generics from hitting the market. Dickson declined to further explain the extent of the group’s lobbying efforts on the trade deal.

Pilma’s stance is also at odds with the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest labor federation, which counts all of Pilma’s labor trustees as members. In its official comments on the TPP, submitted to the U.S. trade representative in 2010, the AFL-CIO expressed opposition to "excessive protections for the producers of name-brand pharmaceuticals" including data exclusivity.

“It’s really a way to ratchet up prices,” says Celeste Drake, trade and globalization policy specialist at the AFL-CIO. “It matters that Americans can get access to generic drugs.”

Strange Bedfellows

While strengthening global intellectual-property standards comes with obvious financial benefits for drug companies, what’s in it for labor?

A 12-year window on biologics “supports U.S. jobs and promotes innovation here in the U.S.,” Pilma’s Dickson says. At the same time, he says, “Weakening the data-exclusivity window has the effect of weakening competitiveness and would send jobs overseas to competitors.”

By contrast, Pilma’s unions reiterated opposition to the proposed trade deal and expressed surprise about the extent of the coalition’s lobbying. “There’s nothing that could happen from TPP that’s good for workers,” says Dave Kolbe, political and legislative representative at the Iron Workers, whose president is also the current chairman of Pilma.

However, Kolbe says, the coalition has come with other benefits. Member companies have agreed to use union contractors for some construction and maintenance work. And more generally, he says, it’s created an open dialogue that didn’t exist before. “This whole idea of unions having to fight employers is long gone,” he says.

Meanwhile, the drug companies benefit from a reliable supply of highly skilled labor for their complex research and development facilities in addition to a broader base of political support. As a top lobbyist for Pfizer put it at a recent meeting of Pilma and the Democratic Governors Association in Beverly Hills, California, “We simply would not be able to achieve our mission without the types of partnerships represented here today.”

A Growing Breed On The Hill

Labor-management associations aren’t new, and their political influence depends largely on the industry, the companies and the unions that constitute them. Nevertheless, these groups have played key roles in a few very specific policy fights in Washington in recent years, taking sides that one might not associate with unions and trumpeting the bipartisanship of their causes.

Last year, the National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans (NCCMP) successfully lobbied Congress on pension reforms that granted sweeping new authority to the trustees of some financially troubled union pension plans to cut benefits to current retirees. Supporters and opponents of the proposal alike acknowledged the appeal of employers and unions, hand in hand, making the case for reforms.

Meanwhile, the Oil and Natural Gas Industry Labor-Management Committee (Ongil-MC), formed in 2009, has pushed for approval of the Keystone XL pipeline and drilling in the Marcellus Shale. (Pilma lobbyist Tim Dickson also serves as executive director of the Ongil-MC.)

For its part, Pilma has enlisted the services of two former high-ranking Teamsters officials -- Chuck Harple and Mike Mathis -- to pressure Congress on intellectual property and trade. Both of them fought trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Free Trade Area of the Americas pact during the past quarter of a century. In 2003, Harple called Nafta “a pyramid scheme designed to benefit corporations and wealthy individuals.”

Neither replied to requests for comment.

Ultimately, by bridging the gap between labor and Big Pharma, Dickson says, Pilma is doing the kind of work the American public craves: “People want us to put aside our differences to try and work together.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.