In Boeing Plant's Union Election, Machinists Face Heavy Opposition From South Carolina Elected Officials

Among the many obstacles facing unions seeking to organize in southern states are the often aggressively anti-union views of area politicians. Consider the following.

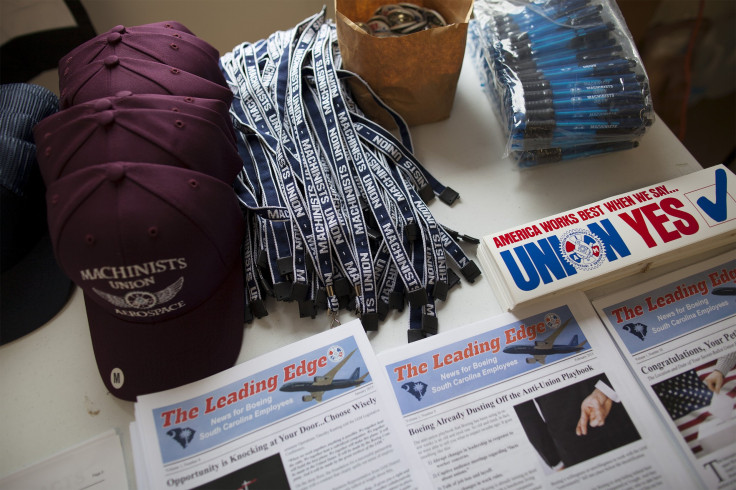

Keith Summey, the Republican mayor of North Charleston, South Carolina, gave an interview last week to local press about a high-stakes union election at the city’s Boeing factory. Some 3,200 production employees will decide on April 22, whether to join the International Association of Machinists (IAM), and Summey was urging workers to vote against the union, which already represents thousands of employees at Boeing’s landmark assembly plant in Everett, Washington.

In the interview, Summey claimed the Machinists harbor ulterior motives. He cited an article from a “newspaper on the West Coast” in which “the head of the union there says this is going to make it easier for them to keep jobs on the West Coast and not lose them to South Carolina.”

In fact, no such story exists. It is possible that Summey is referring to a recent article in the Puget Business Journal that quotes the head of the Machinists’ Seattle-based local at Boeing. But in that story, the labor leader doesn’t say anything about keeping jobs in the Pacific Northwest.

“The Mayor may have misspoke on his own or with help from Boeing, but either way he needs to set the record straight,” union spokesman Frank Larkin says.

A representative for the mayor did not respond to multiple requests to clarify what he meant.

Whether the result of an honest misreading or something more sinister, Summey's remarks underscore a key barrier to the success of organized labor in the South today: Heavy-handed opposition from political officials who benefit from generous free speech protections during union campaigns.

“Employer opposition is no more hostile in the South than anywhere else,” says Kate Bronfenbrenner, a professor at Cornell University’s School of Labor and Industrial Relations. “What’s different between the South and the rest of the country is that politicians are more hostile toward the issue of workers’ organizing. They’re more likely to get involved.”

Summey isn’t the only local politician to speak out against the union at Boeing. His son Elliot, who heads the Charleston County Council, decried the Machinists at a press conference with his father last week. Charleston Mayor Joe Riley has recorded a pro-Boeing radio ad that includes a link to an anti-union website. Gov. Nikki Haley, who lauded the arrival of the Boeing factory in 2009, has also recorded a radio ad for the company calling on workers to reject the Machinists. In her January state of the state address, she said South Carolina has a “reputation internationally for being a state that doesn’t want unions because we don’t need unions. And it is a reputation that matters.” Indeed, the Palmetto State’s union membership rate of 2.2 percent is the second lowest in the nation, after North Carolina.

Historical factors like the predominance of agriculture over manufacturing, entrenched racial hierarchies and the passage of laws that make it difficult for unions to collect dues have all contributed to the diminished presence of organized labor in the South. Another regional challenge for unions is the disproportionate presence of antagonistic politicians: Figures like Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb, who, in 1968, denounced striking sanitation workers backed by Martin Luther King Jr., and Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley, who, last year, wrote letters urging roughly 150 employees at a copper plant considering unionization to vote “no.” (The United Steelworkers ended up winning the election by one vote.)

As union elections near, elected officials can generally say things that employers cannot communicate without risking labor law violations. Neither companies nor unions, for instance, can create an “atmosphere of confusion or fear of reprisals” under election procedures. So long as politicians are not conspiring with either party to do that--a difficult fact to prove in itself--no such standard applies to elected leaders like Mayor Summey.

“There’s a lot of leeway for politicians,” says Paul Secunda, a labor law professor at Marquette University Law School. By contrast, if Boeing were to suggest, as Mayor Summey did, that the outcome of the election could endanger the future of production in North Charleston, the company would likely be slammed with charges of unfair labor practices.

The political outcry in North Charleston harkens back to another recent anti-union campaign at a Southern manufacturing plant: Last February’s defeat for the United Autoworkers (UAW) at Volkswagen's factory in Chattanooga, Tennessee. In that case, Republican Gov. Bill Haslam, U.S. Sen. Bob Corker and top state legislative leaders all spoke out against the UAW, with the latter two suggesting VW would not receive state subsidies if the plant unionized.

Sen. Corker claimed he had been “assured” that if workers voted against the union, VW would quickly announce plans to manufacture a new mid-sized SUV in Chattanooga. It took several months before that happened and Corker repeatedly refused to reveal his source.

The Autoworkers filed objections with the National Labor Relations Board, alleging that comments from Corker and other elected officials amounted to coercive third-party interference, but eventually withdrew their complaint, illustrating, in part, the broad free speech rights of politicians during union elections.

And much like union opponents in Tennessee maligned the UAW’s Detroit roots, Gov. Haley has slammed the Machinists as urban outsiders. “They should pack their bags, head back to Seattle, and stop trying to steal the success of the workers at Boeing South Carolina,” the governor’s press secretary said this month.

Elliot Slater, 55, has worked for the last five years as a mechanic at the Boeing factory and supports the union. While he finds the intervention of Gov. Haley and others upsetting, he says he's trying to tune out the noise and hopes his co-workers can do the same.

“The politicians can say what they want to say,” Slater says. “It doesn’t affect what I’m going through at the plant.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.