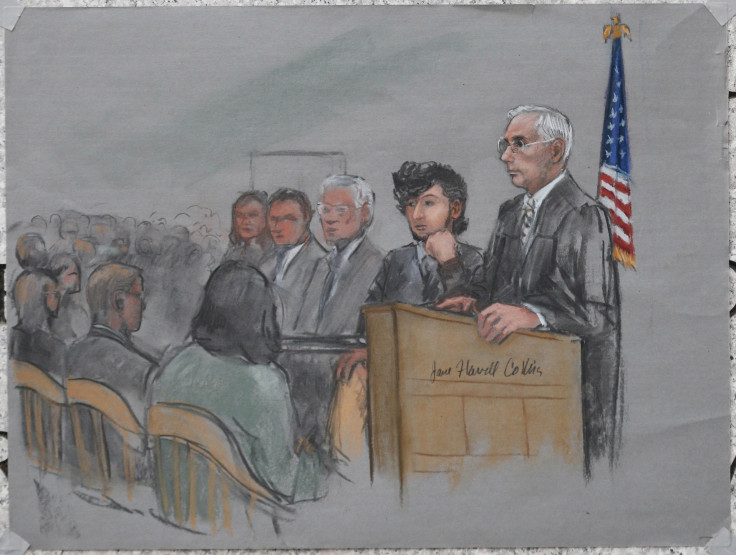

Boston Marathon Bombing Jury Selection: Will Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Get A Fair Trial? Yes, If 'Extensive' Process Works, Legal Experts Say

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s trial is taking place only 15 minutes from the site of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, but he will likely still get a fair decision from jurors -- if attorneys on both sides of the case take their time choosing a jury. They'll have to use extreme care in selecting jurors who are unbiased and able to reach a verdict based solely on the evidence presented in court. Almost all potential jurors will come into the courtroom knowing at least some facts about the defendant and his possible death sentence, but experts say the American justice system will work exactly like it’s supposed to.

Tsarnaev's trial kicked off this week with about 1,200 Massachusetts residents receiving instructions as part of the jury selection process. Choosing an impartial jury in Tsarnaev’s high-profile case could take more than two weeks, but it’s not impossible, said Shari Seidman Diamond, a professor at Northwestern University’s law school in Chicago, Ill. It will just be “a very, very extensive” process, she said.

Tsarnaev is charged with more than 30 federal counts, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, bombing a public place and carjacking. Police said he and his late brother, Tamerlan, constructed and detonated pressure-cooker bombs at the finish line of the 2013 Boston Marathon, killing three and injuring more than 260. They later allegedly killed a Massachusetts Institute of Technology police officer before having a shootout with cops. Tamerlan Tsarnaev died in the confrontation, and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was later arrested nearby. The two ethnic Chechens were allegedly Islamic extremists.

Jury selection started Monday when groups of potential jurors received a questionnaire to complete. Questionnaires are not common but not unheard of in high-profile cases, said Paula L. Hannaford-Agor, the director of the Center for Juries Studies in Williamsburg, Va. In 1994, potential jurors for the O.J. Simpson murder trial had to fill out 79 pages containing 294 questions about their opinions on celebrities, domestic violence, interracial dating, urine samples, math classes and knives.

What’s on the Tsarnaev questionnaire is secret, but when attorneys start examining potential jurors next week, they’ll likely ask about media consumption. One of the biggest criticisms of the jury system is that it favors the uninformed and uneducated, but Bostonians who don’t know about a terrorist attack that happened less than two years ago aren’t the desired audience for Tsarnaev’s trial. “You don’t want stupid people on your jury,” Hannaford-Agor said.

But the Tsarnaev jurors likely won’t know too much, either. In the ongoing retrial to sentence Jodi Arias for the 2008 murder of her lover, for example, about 100 potential jurors were dismissed for having read or watched too much coverage of her first trial. People who remember too many details about the Boston bombing or know someone affected by it will have a tough time being impartial. That won't benefit the defense, legal experts said.

Jury selection is especially challenging in the Boston bombing trial because, if convicted, jurors could decide to sentence Tsarnaev to death. All jurors will have to be death-qualified, which means they neither blindly support, nor morally oppose the death penalty. Death-qualified juries tend to favor the prosecution because all prospective jurors must agree to at least consider death sentences, Seidman Diamond said.

In general, defendants want to go before jurors rather than just a judge because the numbers are in their favor, said "Juries" blog editor and University of Dayton law professor Thaddeus Hoffmeister, of Ohio. For one, it’s easier to appeal to someone in a 12-person group. Jurors also tend to be less jaded about the legal system and not beholden to voters. “At the end of the day, they go home. The judge may have to stand for re-election,” Hoffmeister said.

In that way, the U.S. jury system is “our most democratic institution,” said New York Law School Professor Emeritus Randolph N. Jonakait. It's less susceptible to bias, because the mixture of 12 people’s perspectives means they balance each other out. This is especially true in Tsarnaev’s capital trial, which requires the jury to reach a unanimous consensus.

"It seems strange to many people that we have laypeople deciding whether somebody’s guilty of a crime instead of a judge," Jonakait said. He added, "The real question is, what system would be fairer?"

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.