BP Oil Spill Anniversary: Four Innovative Projects To Restore Louisiana's Sinking Coastlines

Coastal Louisiana is sinking, a problem that dates back nearly a century. Canal systems and oil-and-gas drilling have permanently altered the landscape, causing wetlands to vanish at a dramatic clip. But in recent years, the rate of land loss has accelerated, spurred by catastrophes including Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill, which happened five years ago Monday.

Now Louisianians are racing to halt the destruction and rebuild what they’ve lost. Without wetlands, coastal residents lose natural defenses against hurricane-fueled storm surges and sea level rise. Wildlife and shellfish lose habitats, in turn threatening the livelihood and culinary culture of millions of people.

Here's a look at four innovative solutions in the works today:

1. Surge-Stopping 'Lego Blocks'

Artificial oyster reefs are an increasingly popular weapon against storm surges and forceful waves. ORA Estuaries, a startup company in New Orleans, has designed a system that works a lot like Lego blocks. Heavy rings of concrete -- weighing between 1,400 and 3,000 pounds -- are piled as high and wide as necessary for each reef project. This “stackability” sets the OysterBreak technology apart from other reef designs, says Tyler Ortego, ORA’s founder and only full-time employee. Oysters grow on the rings, adding an extra layer of protection, and the reefs can be easily expanded over time to account for rising sea levels.

Ortego was a graduate student at Louisiana State University when Katrina slammed the Gulf Coast in 2005, killing nearly 2,000 people in the U.S. and causing $100 billion in damage. After the storm, “The whole national conversation shifted to, ‘How do we restore coastal Louisiana?’” he recalls. “That really solidified for me that there’s a real business opportunity here.”

ORA has so far built three miles of oyster reefs from eight projects in Louisiana. A ninth project is in the manufacturing stage, and two more projects are planned in Mississippi and Alabama. In March, Ortego won the “Big Idea” pitch challenge at New Orleans Entrepreneurs Week, which came with a $25,000 prize to help fund his company’s expansion and to develop new reef technology. “We’re really gaining traction,” he says. “We’re reaching out to the whole Gulf Coast and Atlantic Coast as well.”

2. Recycled Reinforcements

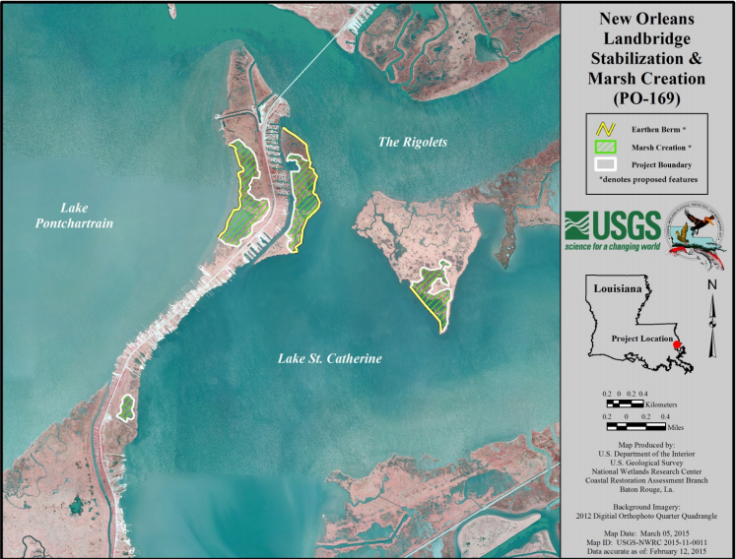

Construction crews are salvaging concrete from a bridge destroyed by Katrina and using the materials to fill in an eroding marshland outside New Orleans. More than 200,000 tons of crushed concrete from the old Interstate-10 Twin Span Bridge will soon be spread out along the Orleans "landbridge," a nine-mile stretch of marsh that separates two major lakes, Pontchartrain and Borgne. The landbridge is gradually eroding, and if it disappears, around 1.5 million residents in New Orleans and the Northshore community could suffer even more damage from storm surges.

The $17.5 million project is one of more than 100 initiatives included in Louisiana’s $50 billion, 50-year coastal master plan, which was approved in 2012 in response to destruction from hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The state-led strategy aims to increase flood protection for coastal communities and create a more sustainable coastline.

The landbridge project is in the engineering and design phase and could take several years to finish. When completed, it’s expected to prevent the loss of 110 marshy acres as well as the largest urban wildlife refuge in the nation.

3. Urban Waterways

Inspired by Dutch design, the Lafitte Greenway near New Orleans’ French Quarter will transform an abandoned canal system and railroad route into a feat of flood-proof engineering.

The city’s streets frequently flood during heavy rain events because the water has little place to go. Underground storage capacity for storm water is minimal, and existing drainage networks are overwhelmed. Pumping the water out of New Orleans is causing the city's foundation to sink, which, combined with wetland loss, is making residents even more vulnerable to flooding.

In this context, the $9.1 million greenway project is only a small solution for an enormous problem, though the design could be replicated throughout New Orleans if successful. The 2.6-mile bicycle and pedestrian parkway will include shade trees and plant meadows to help absorb rainwater. Bioswales, which are natural drainage ditches, will help contain and minimize the excess storm water. An unused 25-acre parcel will become a “water garden,” including a public pool and water filtration ponds that collect rainwater.

The goal of the project, led by David Waggoner of the design firm Waggoner & Ball, is to accommodate the influx of water without inundating homes or overwhelming sewage systems. Construction on the Lafitte Greenway started in March 2014. The park is scheduled to open to the public this summer and is part of a $6.2 billion urban plan to address the water problems in Greater New Orleans.

4. Man-Made Marshes

Lake Hermitage in southeastern Louisiana lost nearly 40 percent of its marsh from 1932 to 1990, state officials estimate. The marsh is continuing to vanish, and by 2050 the lake could lose another 28 percent of the acreage it had in 1990. To reverse this destruction, the state is building new marshes and restoring the lake’s shorelines.

Over the past few years, workers have piped sediment dredged from the Mississippi River into the lake, filling open expanses of brackish water and fragmented wetlands with fresh soil. The Lake Hermitage project ended a few months ago, restoring 650 acres of marsh.

The area today looks like a barren prairie, with scattered clumps of green grasses and a smattering of puddles. In time, however, the plants will flourish and birds and fish will form nesting grounds on and near the marsh. The new land also serves as a buffer between lakeside communities and waves and storms in the Gulf of Mexico.

The $50 million project was built in part with BP’s money. After the 2010 oil spill, federal officials launched a Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) to quantify the extent of environmental damage from the 3.1 million barrel spill. The full NRDA process is expected to last a decade, so BP agreed in 2011 to pay $1 billion for an early restoration program. Around $700 million of that bucket has been spent or set aside for projects, including this and other marsh creation initiatives. BP is currently facing fines of up to $13.7 billion for violating the U.S. Clean Water Act.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.