Brexit: Irish Business Fears Border Controls, Tariffs, Uncertainty, While Some Eye Increased FDI

LONDON — Sole traders or a small manufacturing businesses don’t tend to share the same economic concerns as a major multinational pharmaceutical company, but the possibility of the British public voting to leave the European Union in June is uniting diverse business interests in one of the U.K.’s key trading partners: Ireland.

A survey published by the Irish Exporters Association this week found the main concerns of companies included the possible reintroduction of border controls (73 percent), the reintroduction of tariffs (61 percent), the impact on Ireland’s economic growth (83 percent) and the possible restrictions on movement of capital, people and services.

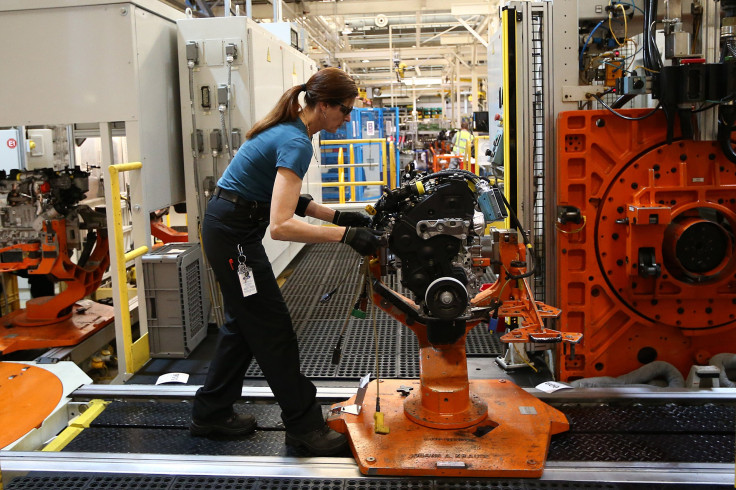

In nuts-and-bolts terms, such restrictions could affect a wide range of sectors in Ireland’s economy. Ireland’s pharmaceutical industry, for example, which plays a major role in its export economy, could suffer disruption to the supply chain to hospitals, pharmacies and subsupply between their manufacturing plants across the Irish Sea and the English Channel, trade consultant John Whelan wrote in the Irish Examiner.

On a micro level, the BBC highlighted the example of an Irish confectionery manufacturer, who fears a Brexit will increase the price or disrupt the supply of sugar that he sources from the U.K.

Research from Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute also found the merchandise trade between the two countries is concentrated in a few product types, which implies increased trade barriers for the most important products would have a particularly significant impact on the volume of trade between the two countries.

“The problem in all of this is uncertainty,” Simon McKeever, chairman of the Irish Exporters Association, told International Business Times in an interview. Other business leaders declined to speak to IBT on the record, some citing concerns about stirring up unnecessary panic among their U.K. partners.

“I suppose that the immediate concern is that 60 percent of [our members] are saying that the weakening of sterling in advance of the vote has already hit them. Sterling has weakened by 11 percent since Nov. 19. It's a very sudden movement and that is very worrisome for them. The biggest short term concern is: Will sterling continue to weaken ahead of the vote?”

In addition to the issues raised by the survey, McKeever also raised concerns about any future regulatory regime governing trade between the U.K. and the EU in the event of a Brexit.

“There is this misconception in Ireland that we can right now, on our own, renegotiate a free trade agreement with the U.K., and that is not the case. ... Because we cannot negotiate a separate trade relationship with the U.K., we would be worried that things like customs barriers would be imposed in either direction. The U.K. will want a separate trade agreement with the EU if they come out, but I’m not quite sure how that is going to end up,” McKeever said.

“You have to ask yourself what line the EU will take against the United Kingdom, because with the U.K. coming out — is there a danger that other countries might want to come out? I would wonder whether the EU will take quite a hard line with the U.K. [if they leave], and that is not good for us and it’s not good for the U.K.”

With more than 1 billion euros ($1.1 billion) in trade between Ireland and the U.K. every week, the stakes for Irish companies in the Brexit vote are high. Where some in Ireland, however, see peril, others see opportunity.

Martin Shanahan, the chief of Ireland’s Industrial Development Authority, the body responsible for attracting and facilitating foreign direct investment into the country, said in a recent interview his organization is having “increased and heightened” meetings with financial services companies, considering relocating in the event of a Brexit. Such moves already may have begun, with Credit Suisse opening a 100-seat trading desk in Dublin earlier this year.

Among the businesses surveyed by the Irish Exporters Association, 60 percent said a Brexit would hurt their company while 40 percent said it could increase foreign investment in Ireland. Other surveys, such as one carried out by the Irish Times, suggested Irish businesses, for now, are more concerned with the risks than any potential benefits a Brexit could bring.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.