Can Tasmanian Tigers Be Revived From Extinction? Scientists Sequence DNA

Scientists might one day be able to bring the Tasmanian tiger back from extinction due to newly discovered information about the animal’s DNA.

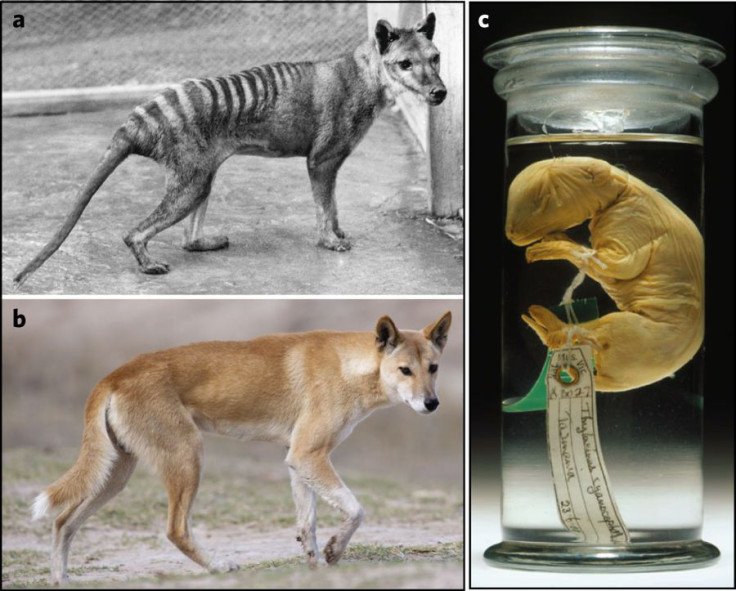

Although the Tasmanian tiger sounds like a cat and looks like a dog, it is actually a marsupial, from the same group of animals that includes kangaroos, wallabies and koalas. It diverged on the evolutionary tree from the dog line about 160 million years ago. The sandy-colored creature with dark stripes on its back, known officially as thylacine, lived in Australia for a few million years before humans showed up. It is believed to have gone extinct in the 1930s due to conflict with humans, who hunted the animal because it preyed upon their sheep.

Its status might change one day, however. A team has reported sequencing the animal’s genome in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, and having that genetic information could one day be used to revive the species.

The DNA came from a Tasmanian tiger pup that had been preserved in alcohol after being recovered from its mother’s pouch more than a century ago, according to the study.

In addition to getting a genetic template for a species lost to history, the scientists have learned more about the inner turmoil that the Tasmanian tiger was going through even before humans showed up and hunted them to death.

According to the research, the thylacines did not have a lot of genetic diversity, which would have made it more vulnerable even without human interference. Genetic diversity refers to the volume of different traits creatures are carrying in their DNA and is important for adapting to changes in their environment and surviving. Tasmanian tigers saw a “steep decline in diversity” between about 70,000 to 120,000 years ago that could have been linked to natural forces.

“The population decline appears to have begun before the human colonization of Australia … and overlaps with climate changes associated with the beginning of the penultimate glacial cycle,” the study explains.

The DNA analysis worked because of the way the 108-year-old pup was preserved in ethanol.

“[In the past], we’ve done a lot of work getting DNA from all sorts of [thylacine] specimens from all over the world, a lot of pelts, a lot of dried skin and bone, but it’s super-fragmented,” study co-author and evolutionary biologist Andrew Pask told Australian news outlet ABC.

Bringing an extinct species back from nothingness, a process called de-extinction, is a controversial topic that includes debate on whether technology will actually ever be able to achieve such a feat.

Although the term “de-extinction” might conjure images of scientists using DNA to completely regenerate species like dinosaurs and woolly mammoths in a Jurassic Park-type manner, there are other methods. For example, scientists in the Galapagos Islands are trying to revive an extinct tortoise by selective breeding of its close living relatives.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.