Chagas Disease: How A Silent Tropical Parasite Prospers In The US

Maira Gutierrez is 42 years old, but she knows that at any moment, she could drop dead from a heart attack. Although she eats a heart-healthy diet, doesn’t smoke and is not overweight, she knows that nothing can eliminate the threat of her heart failing her. That's because Gutierrez has a tropical disease known as Chagas, and the parasites that cause the condition are inching steadily, irreversibly through her heart. A routine blood screening caught the disease too late for doctors to cure her.

Though Chagas thrives in improverished rural areas in the developing world, Gutierrez doesn't live in a remote village, far from decent medical care. She has been a Los Angeles resident for most of her life. Still, her condition went undiagnosed for years. Her experience is far too common in the United States, where medical experts say Chagas has become a lurking public health threat. The disease often goes overlooked because of whom it primarily affects: immigrants. Physicians do not regularly screen for Chagas, and because it causes heart disease, which is relatively common from other causes, people can die without ever being diagnosed. Treatment is available solely on an experimental basis and effective only if the disease is caught early.

Last week at the World Health Assembly in Geneva, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who is also serving as current president of the G7 nations, pledged a renewed focus on fighting a handful of debilitating diseases that afflict the world’s poorest people, including Chagas. Yet it is because of this status, as a scourge of developing nations, that the most basic aspects of treatment -- a proper diagnosis and timely intervention -- are still sorely lacking for those with Chagas in the U.S.

In the U.S., most people who have Chagas disease contracted it while they were growing up or living in rural areas throughout Central and South America. There, the disease is still readily transmitted. In 1981, Gutierrez moved at age 7 with her younger sister from rural San José Las Flores in El Salvador, where they lived in a mud home with their grandmother, to join their parents in a rented house in Bell, a district of Los Angeles.

Gutierrez went to donate blood when she was 23. Shortly after, she received a letter saying her blood could not be used and she should contact the CDC. She nervously called the 800 number, and learned that she had tested positive for Chagas.

A Deadly Kiss

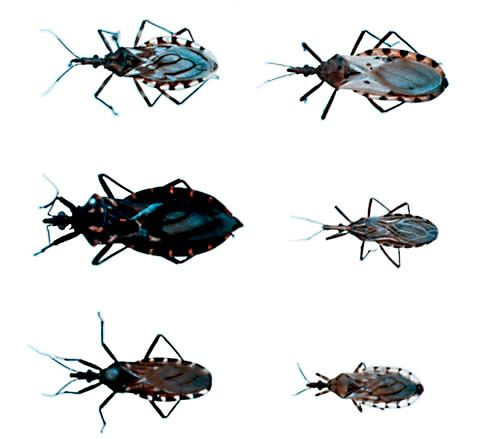

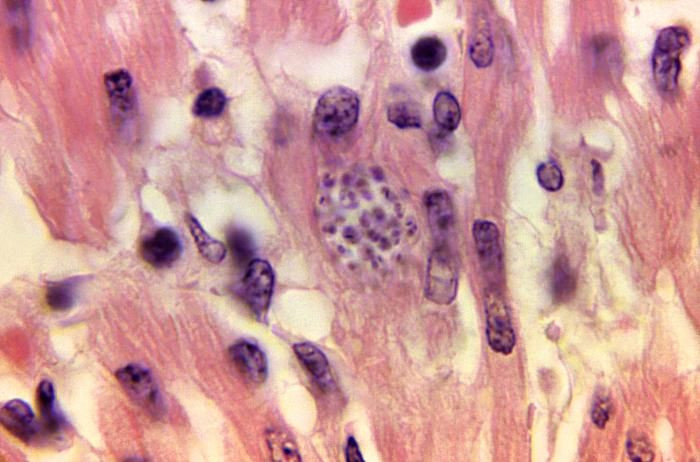

Gutierrez will never know precisely how or when she contracted the disease. Ordinarily, it starts with a parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi. The parasite is carried by blood-sucking triatomine bugs, also known as “kissing bugs,” which can be found in the cracks and walls of mud homes in Latin America, like the one Gutierrez lived in until she was seven. An infected bug crawls out at night and bites a person, usually on the face, and then defecates on or near the bite. A person becomes infected if the feces, which contain the parasite, touch the wound or other orifices, like the eyes.

Once the parasite has entered the bloodstream, it seeks out organs and tissues to infect. It often ends up in the heart, where it causes inflammation that interrupts electrical conductivity and causes arrhythmias, or irregular beats. About a quarter of infected patients develop heart disease, often after living with Chagas for years or even decades with no symptoms. By the time heart problems develop, though, the disease is more or less irreversible.

Researchers are increasingly discovering the significant role Chagas plays in heart disease in certain parts of the U.S. Dr. Sheba Meymandi, a cardiologist and the director of the CDC’s only "center of excellence" for Chagas treatment in the country, which is located at the University of California, Los Angeles, says about 5 percent of Latin American immigrants in the area who had heart failure tested positive for Chagas in 2000. Today, that rate has risen to 19 percent.

Meymandi says her center has screened a total of 6,000 patients in the primarily Latin American community, even those without heart disease, and 1 to 1.5 percent have Chagas. “When you consider that there are millions of Latin American immigrants in this country, that’s a pretty huge number,” she says.

An Invisible Affliction

Eight million people are infected with Chagas worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, and the disease is commonly viewed as scourge of Latin America -- not as a disease that anyone in a developed country like the U.S. would acquire. “There is a big stigma,” said Mario Grijalva, a biomedical researcher at Ohio University who has studied Chagas for 20 years. “If you have a disease like this, you are labeled as having a disease that associates you with poverty and low economic status.”

In reality, the CDC estimates 300,000 people in the U.S. are infected with Chagas, though Melissa Nolan Garcia, an epidemiologist at the Baylor College of Medicine in Texas who has studied Chagas, believes the real figure is higher.

“It is not a very tight estimate,” said Susan Montgomery, who leads CDC’s epidemiology team on parasitic diseases. “It’s based on a lot of assumptions, and it’s the best we could do with the data available.”

It’s hard to know exactly how many Americans have Chagas because patients are rarely tested for it, with one exception: blood donation screenings. Blood banks began screening for the disease in 2007 -- Gutierrez’s 1997 donation was caught in a random experimental screening -- and those who test positive get a letter in the mail warning them. Otherwise, patients have no way of knowing they’re infected.

“Blood donation screening is playing a pivotal role in identifying people who were infected,” said Dr. Susan Stramer, executive scientific officer for the American Red Cross. These screenings pick up antibodies, or proteins, in the blood that respond to the presence of a specific disease. The CDC estimates that one in 27,500 blood donors tests positive for Chagas.

Besides a lack of testing, another of the biggest hurdles to treating Chagas disease in the U.S. is physician awareness. American doctors are generally ignorant of the disease and often don’t think to screen a patient who grew up in rural regions of South America. Or they may assume that heart problems were caused by lack of exercise or an unhealthy diet.

The CDC tries to inform doctors about Chagas disease through an educational course that physicians can take for credit toward their license renewal. “Physicians should regularly consider this in their patients,” suggested Garcia, the Baylor epidemiologist.

Once a case is detected, patients face a lack of treatment options. The prevalence of Chagas has done little to spur major pharmaceutical companies to create a vaccine or better medicines to treat it. Chagas is one of 17 diseases labeled as neglected tropical diseases by the World Health Organization because they affect large numbers of the world’s poorest people but have historically received little attention and funding.

That’s because drug companies develop drugs to treat illnesses affecting people who can afford to pay for the medicine, Rachel Cohen, regional executive director of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative. Sick people who live in huts in rural parts of Latin America and Africa simply don’t qualify. “They fall outside of the market,” Cohen points out.

There are currently only two drugs to treat Chagas: the antiparasitics nifurtimox and benznidazole. They are a logistical pain to obtain, because they’re not FDA-approved, and they also wreak havoc on the human body. Most important, they are effective only if the disease is caught early on. There’s no vaccination for Chagas, either, although researchers at the Sabin Vaccine Institute are working on developing one.

When Gutierrez was first diagnosed in 1997, she went to a specialist who told her there was no treatment for Chagas. It wasn’t until 2008, when her sister frantically called her about a report she’d just seen on television, that she once again sought treatment, this time at the UCLA center in Los Angeles. For two months she took nifurtimox, losing her appetite and with it, 25 pounds. Gutierrez is certain the medication did not -- and could never -- cure her, because tests suggest she contracted the disease decades ago.

‘I Can’t Be The Only One’

Triatomine bugs are found widely throughout the southern United States and have been for decades. Unlike the bugs in Latin America, they mostly live in forests far from people’s homes and feed primarily on animals, so Montgomery says that generally, Americans are safe. However, a handful of U.S. residents with Chagas disease are known to have been infected on American soil. The disease is not easily spread between people, though between 2 and 10 percent of mothers who are infected with Chagas will transfer it to their babies. “It’s far less than one in a million,” Stramer of the Red Cross says of the chances of contracting the disease in the U.S.

Candace Stark, 51, is one of those unlucky victims and has experienced all the frustrations of Chagas firsthand, from the stigma to the medical community’s lack of awareness. In July 2013, the Texas resident went to donate blood. That August, she received a letter. “That’s how I found out,” she says. “I got that letter in the mail saying, ‘Hey, you’ve tested positive.’”

Two days later, Stark saw a doctor, who knew little about the disease and referred her to an infectious disease specialist, who had yet to treat a patient with it. He retested Stark, then sent off paperwork to the CDC to procure the drug benznidazole. After giving Stark her third blood test, the agency cleared her for the medication -- which took 24 weeks to arrive.

“We’re not rich, but we’ve always lived well,” Stark says in her Southern twang, citing her own brick house, plus the one her parents bought six years ago. Because she lived in a modern home and had never left the U.S., Stark could not fathom how she had contracted the disease, until last August, after her mother passed away.

“I was going through some of the stuff in her closet, trying to find some stuff for the memorial,” Stark recalls. “I actually found one of the bugs.” Stark sent the kissing bug, dead but fully intact, to a lab at Texas A&M University for testing. It came back positive for Chagas.

After her diagnosis, Stark made sure everyone in her family -- her yellow Labrador included -- was specially tested for Chagas. They were all negative. “The way I figure it, surely I can’t be the only person in my little old town with this disease. Not when I personally have seen the bug myself,” she says.

Stark lives in La Grange, a town of 4,675 nestled in one of the many bends of the Colorado River between Austin and Houston. When she wondered aloud to her doctor if she should mention it her neighbors, he responded, “Do you know who Typhoid Mary is?” -- a reference to a cook in the early 1900s who was suspected of infecting more than 50 people with Typhoid.

“People are scared of it because they don’t know what it is,” Stark says. She now attends conferences about Chagas herself and shares what she learns with her doctor.

Stark will never know if the drug she took worked. Antibodies remain in the bloodstream, even a person has been cured. She says that is the hardest part.

“Even though I took the medication, I don’t know if I’m going to one day find out that my heart is enlarged, or that I’m going to die early,” she says. “I won’t know ‘til I’m dead and gone and they’ve done an autopsy.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.