How Three Scientists ‘Marketed’ Neglected Tropical Diseases And Raised More Than $1 Billion

Imagine a single disease that inflicts blindness, deforms limbs, stunts growth -- one that affects the daily lives of more than 1 billion people in numerous countries around the world. If there were such a pandemic, it would trigger frightful headlines and a call to action for funding to help drugmakers locate and distribute a cure.

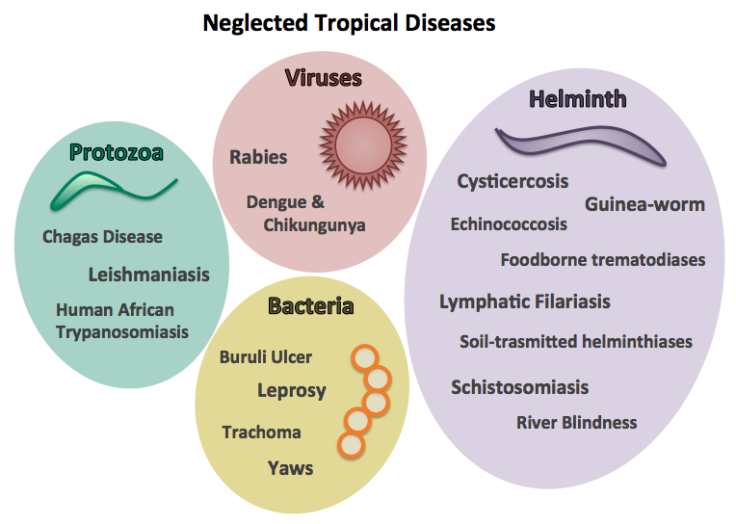

In reality, a rash of 17 diseases plague the world's poorest communities with precisely these problems but these maladies were largely ignored until three researchers came up with the surprisingly simple idea to "market" them to politicians and private foundations collectively as "neglected tropical diseases." The result has been a surge of funding in the last decade.

“Nobody had a clue about them,” David Molyneux, former director of the Center for Neglected Tropical Diseases at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the U.K., says. Realizing this, he and a few others formulated a plan – they would lump together all the diseases associated with poverty which struggled to gain attention, and call them “neglected tropical diseases” since they were primarily found near the equator.

It certainly didn’t help that most of these maladies had long been eliminated from the developed world and many were impossible to pronounce on a first attempt: schistosomiosis, onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis and leishmaniases, for example.

This simple strategy -- to create a strong brand that would allow advocates to pitch a myriad of forgotten diseases at once -- has proven remarkably effective. All together, governments and aid organizations have pledged at least a billion dollars to neglected tropical diseases since 2006. An aggregated estimate of 1.4 billion people who are affected by these diseases has made headlines and prompted pharmaceutical companies including Merck, GlaxoSmithKline and Bayer to donate 1.4 billion treatments each year.

The World Health Organization now identifies 17 “neglected tropical diseases” – a term that holds no clinical or scientific relevance but which has elevated little-known conditions such as trachoma, hookworm and dengue fever in discussions of global health long dominated by more established causes such as HIV/AIDS, malaria or tuberculosis.

“I think the term ‘neglected tropical diseases’ is a brilliant umbrella term," Dorie Clark, a branding expert and author of Stand Out, says. "It allows funders to feel like they are addressing something important that has been hidden for a long time.”

That phrase originally grew from a sense of frustration among researchers back in 2002, when the United Nations announced the Millennium Development Goals to establish a framework for global development. The sixth goal was written as: “Combat HIV/AIDs, malaria and other diseases.”

Peter Hotez, president of Sabin Vaccine Institute and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, worried that it would be hard to get people excited about fighting “other diseases.” The overall disease burden, a figure often cited by public health officials and leveraged in funding pitches, was too small for any single “other” disease to stack up against malaria or HIV.

“They created a third category called ‘other diseases’ which was a total disaster from a public advocacy point of view,” Hotez says. “It created a two-tier system of disease.”

Not long after, the World Health Organization hosted a meeting in Berlin in 2003 about illnesses in the developing world. It was there that attendees including Hotez and Molyneux decided to start using the term “neglected tropical diseases” to advocate for those which afflicted the world’s poorest people but lacked funding and were left out of most discussions on global health. “It was really a branding exercise,” Hotez says.

Molyneux floated the term in a commentary published to The Lancet in 2004. A year later, the World Health Organization held another meeting in Berlin and the term was “rubber-stamped,” as Alan Fenwick, director of the Schistosomiosis Control Initiative at Imperial College London who also took part in brainstorming at the original meeting, puts it.

Since “neglected tropical diseases” came into popular use, funding has been far easier to come by for those who work on these maladies. WHO created the Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases in 2005 and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation dedicated at least $114 million to neglected tropical diseases in 2006. The U.S. Agency for International Development quickly pledged another $212 million.

“Marketing is a big aspect of it,” Josh Michaud, associate director for global health policy at Kaiser Family Foundation, says. “Had they not come up with this term, I don’t think we would be where we are in terms of funding and attention on this issue.”

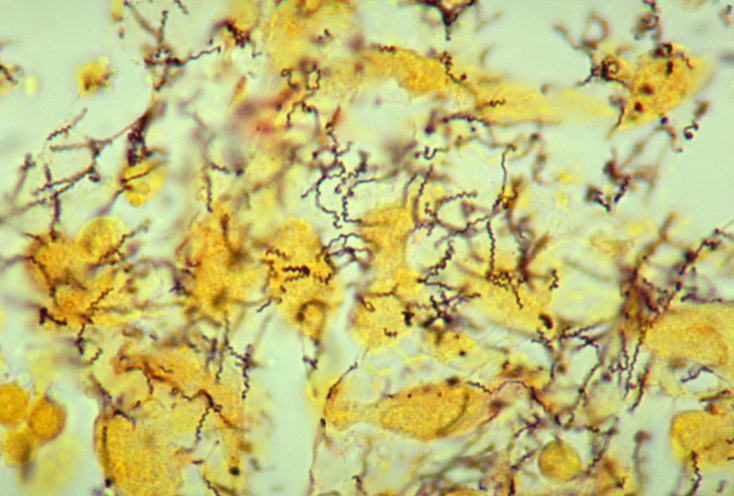

Before the term launched, there was a smattering of money dedicated to “other” diseases – the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation had committed $30 million in 2002 to fighting schistosomiosis, which is transmitted by fresh water snails and can cause internal scarring or learning disabilities. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, a researcher named Kenneth Warren at the Rockefeller Foundation had led an effort to address the world’s “Great Neglected Diseases” which included malaria and schistosomiosis, but that legacy had slowly faded.

Today, the global commitment to other diseases is still far greater – the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has committed $3.6 billion to fight malaria, AIDS and tuberculosis – but Fenwick says those who work on the neglected diseases are nonetheless quite pleased.

“We've made such fantastic progress that last year, 700 million people were treated with one or more of the drugs needed to treat those diseases,” Fenwick says.

Fenwick says the impact goes beyond raising money -- leaders in sub-Saharan Africa who made no mention of any of the neglected tropical diseases in the national health plans they published in 2002 have now all formed strategies for addressing these diseases. Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO regional director for Africa, announced on May 2 that she plans to establish an entity to oversee all work related to neglected tropical diseases across the continent as part of an international effort to eliminate some of these illnesses by 2020.

“This is arguably one of the world's largest public health programs ever next to childhood immunizations,” Hotez says. The USAID office announced that it had administered its one billionth treatment for neglected tropical diseases in October 2014.

Hotez embraces the idea that branding can play a major role in furthering public health. In conversation, he is quick to offer catchy phrases which highlight complex problems -- he coined the term “Blue Marble Health” for the idea that health issues related to extreme poverty occur not only in developing nations but also among the poorest people in the world’s wealthiest countries.

As it turns out, this approach doesn’t only work from a marketing perspective – bringing neglected tropical diseases under a single term has also helped align efforts to study and treat them. Many of these diseases are now prevented through programs that simultaneously give out drugs for five illnesses at once.

Fenwick admits that the global success in bringing attention to the supposedly neglected diseases may simultaneously be rendering the term obsolete.

“If 700 million people are receiving treatment free of charge, how neglected are they?” he says. “However, having sold the brand, we don't want to destroy it quite yet.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.