China And Afghanistan’s Minerals: Archaeologists Still Scrambling To Save Mes Aynak

More than a decade ago, the world was outraged when the Taliban destroyed two massive Buddha statues in Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Valley in a vendetta against all non-Islamic art. Today, an even larger and older collection of artifacts is under threat, but this time the conflict has more to do with economics than religion.

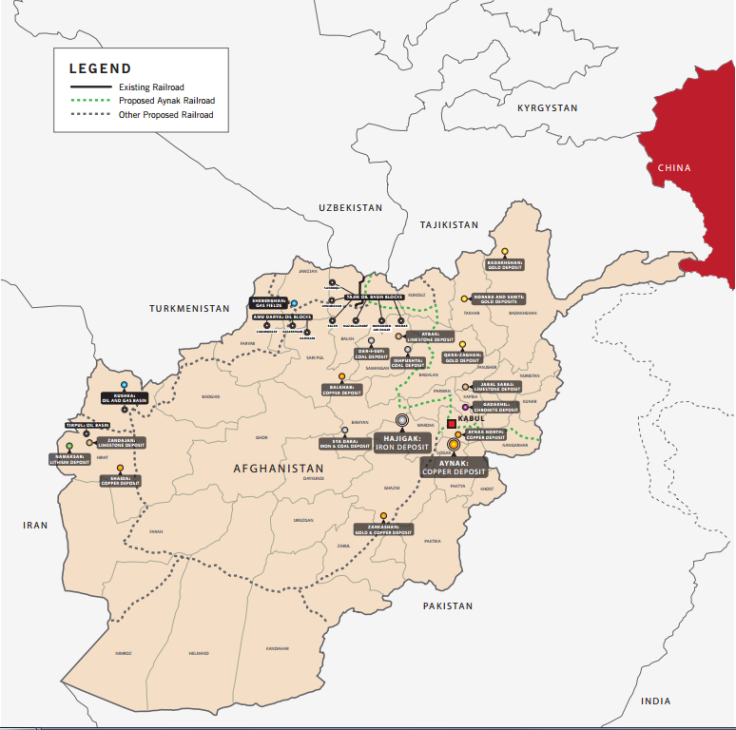

Mes Aynak is a 9,800-acre archeological site in Afghanistan’s Logar Province. It was once a major city on the ancient Silk Road and is home to structures dating back more than 2,600 years. Archeologists say it’s a cultural goldmine, but others are more concerned with what lies beneath it -- 5.5 million metric tons of high-grade copper ore.

Six years ago, China’s largest mining company signed a $3 billion agreement with the Afghan government for rights to the site, a move cheered for its potential to boost jobs and the country’s struggling economy. But the decision left archeologists scrambling to recover what cultural heritage they could before work on the mine began. Even though the company has delayed its project for other reasons, tight budgets and a lack of assistance from the Afghan government mean the ancient city is far from safe.

“It was very clear since the beginning that the provisional schedule for mining was overly optimistic,” said Philippe Marquis, an archeologist at the French Archeological Delegation in Afghanistan, which started working at Mes Aynak a year after the deal was inked.

The area itself, less than an hour’s drive from Kabul, is home to some of the oldest Buddhist artifacts in Central Asia. So far, archeologists have identified more than 70 sites in the valley, including a handful of monasteries, monuments and more than 1,000 statues.

Experts have called the site “one of the most intriguing ancient mining sites in Central Asia, if not the world,” noting the city’s religious and economic significance over the millennia.

Funded by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Afghan archeologists received more than $1.5 million worth of equipment and guidance for the project, according to Marquis. A year later, the World Bank asked the group to assess the site and propose a working timeline. Since then, the plan has been amended at least 20 times.

“The main problem of this excavation is the very low level of local expertise and the lack of infrastructure,” Marquis said. “The quality of excavation is not very high, but the biggest problem is the management of what has been found.”

Archeologists are currently using a strategy known as “rescue excavation,” which is similar to the way looters operate. While traditional methods would require workers to painstakingly uncover, document and preserve the site as it is, archeologists are trying just to record what they find and remove anything valuable before it's too late.

In 2008, the China Metallurgical Group Corp. promised $3 billion to the Afghanistan Ministry of Mines for a 30-year lease on the site, with plans to start digging within five years, and build railways and other infrastructure projects to support the mine.

“As Afghanistan emerges from conflict and transitions from an economy supported by large amounts of foreign aid to a self-sustaining economy, it needs to use its natural resources to help fuel growth,” World Bank researchers wrote in a report on the project at the time, adding the country has an estimated $1 trillion in natural resource assets.

They also projected the Mes Aynak project in particular would create 12,000 direct jobs and 62,500 “induced” jobs while adding $250 million in annual revenues once the mine hits capacity -- no small thing considering more than 90 percent of Afghanistan’s current economy depends on aid and military spending.

“The Aynak project represents the largest private sector project in the country’s history, and it will generate more jobs, revenues and enhancements to Afghanistan’s infrastructure than any other single project to date,” the Afghan Ministry of Mines wrote in a 2012 statement.

But not everyone was as pleased. The Afghan government has never published details of the agreement despite widespread criticism from watchdog organizations such as Global Witness, which investigates economic networks behind conflict, corruption and environmental destruction. In the 2012 report “Copper Bottomed?” Global Witness researchers outlined the various problems with the deal’s transparency.

“Since the whole contract has never been published, it’s hard to evaluate what exactly has been promised,” said Jodi Vittori, the firm’s Afghan policy adviser. She explained that the lack of data amid a swirl of rumors has made it difficult to determine whether advantage is being taken of any party. Meanwhile, many are worried the country could be experiencing a “resource curse.”

While the site would provide necessary jobs and an economic boost, she and others said they fear the Chinese deal, shrouded in mystery, could put Afghanistan at risk of a “resource curse,” in which foreign investors take advantage of its massive mineral stores without much help to the country. Indeed, it wouldn’t be the first time China would be accused of such things. The vast majority of Chinese investment in other developing regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa, is focused on resources, which has led to a great deal of criticism and claims the economic heavyweight is exploiting low-income countries.

“My fear is that people won’t really care about this until after the fact,” said Brent Huffman, a documentary filmmaker and professor at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, who has been recording the excavation process since 2011.

His documentary “Saving Mes Aynak” follows the local Afghan archeologists working at the site. In January the film was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Grant and was recently picked up by Kartemquin Films.

“My fear is that this is just another way Afghanistan is going to lose. With Chinese and Indian companies taking valuable resources out of the country, Afghanistan is left with these toxic craters. My fear is that Mes Aynak is a stepping stone toward that,” Huffman said.

In Afghanistan, “China is generally viewed in the region as a benign power, because it doesn’t get involved politically,” said Marvin Weinbaum, political science professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who formerly worked for the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

“That said, it doesn’t want the place to become chaotic,” he said, referring to this year’s election, which, fraught with charges of fraud and corruption, has only served to increase tensions in the country as it plans a transition to a self-sustaining economy.

Amid the instability, MCC moved to renegotiate its contract, delaying the dig in the face of a slowing Chinese economy, falling copper prices and increased instability. But while the development should have given archeologists more time to work, that isn’t exactly the case. In the face of budgetary mismanagement and growing insecurity, recovery work on the site has ground to a halt.

“All budget for archeology got stuck somewhere between the ministries of Finance and Mines,” Marek Lemiesz, an archeologist with the Afghan Ministry of Mines, told International Business Times. “It seems to be now clear to everybody that Mes Aynak should be, in normal circumstances, excavated for at least 20 years and we have been given a maximum three years.”

He said all archeological activities were cut off in May on orders from the Ministry of Mines for a variety of reasons, including that Afghan archeologists had not been paid for more than seven months and finally went on strike. But money isn't the only reason: Workers are also worried about their safety. This year’s Afghan election was fraught with fears of fraud and corruption that have only increased tensions, especially in the rural areas where local groups can pose a threat to foreign workers.

“Another serious issue is significantly decreased security in Logar,” Lemiesz said. “In the past months we were faced with a series of serious incidents such as rocket attacks, IEDs [improvised explosive devices] set inside the so-called ‘Security Zone’,” he said, adding he was “seriously concerned” about the safety of expats on the ground.

The region is an important one for China. “There are so many factors that make Chinese investment of economic, political and strategic capital in the region a logical posture,” Kendrick Kuo, China and foreign policy specialist and author of the Asian Crescent blog. He said that Chinese interest in the region goes as far back as the 1980s. While its largest competitor there is Russia, its advantage is greater economic clout.

“The delay on the Mes Aynak mine is arguably a wait-and-see tactic to see how the chips fall,” Kuo said. “China can’t help but to be involved in Afghanistan, especially economically, but it is also not as risk-tolerant as some may think,” he said.

The city is still likely doomed to be demolished and replaced with a copper mine, but for now, that fate may be delayed for a bit longer.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.