China-Latin America Relations: In Ecuador, Dependency On Beijing Financing Of Development Projects Raises Fears, Uncertainty For Some

MANTA, Ecuador – The long stretch of roadway snaking through the parched, rolling hills outside this sleepy Ecuadorean port city will one day wind up at the foot of one of the country’s most buzzed-about development projects: a mega-refinery that will transform Ecuador into a formidable force in the region’s oil and gas industry. When the grand structure is completed, Ecuador will dramatically streamline operations for its biggest export, jobs will flow to the surrounding communities and China, Ecuador’s largest creditor, will have footed the bill.

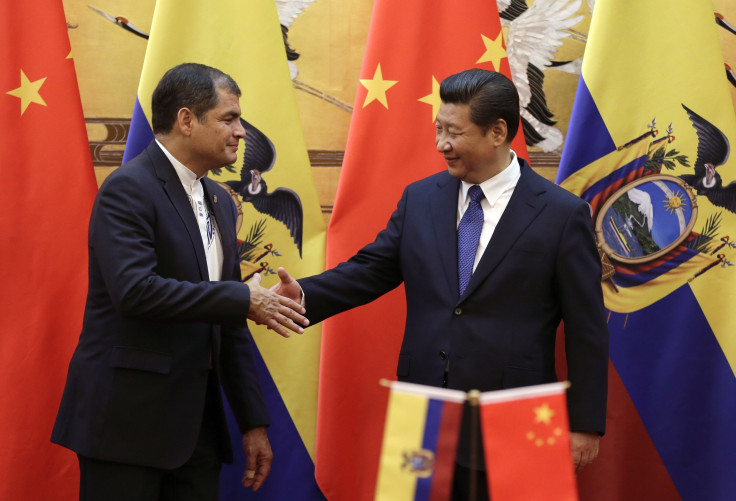

At least, that’s been the vision of Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa as his government has tried to seal a financing deal with China for the project for several years. But for now, the solitary “REFINERIA” sign that stands at the side of the road points to a vacant, sandy patch of land and a few completed canals, and questions have continued to bubble over whether the funds from China needed to finish the multibillion-dollar project will even come in.

“I have doubts about it, a lot of doubts,” said Fernando Delgado, a 25-year-old mechanic and resident of Manta, a city that currently revolves around the tuna industry but stands to become an important petroleum hub in Ecuador if the refinery ever gets completed. “The refinery is supposed to be for Ecuador’s future, but so far there have been no results.”

The stalled project, for which Ecuador has already spent more than $1 billion, had been billed as a game-changer for the tiny Andean nation, which relies on oil for roughly half its export revenues but doesn’t yet have the refining capability to meet its own domestic demand for fuel. But for many Ecuadoreans, it’s become a potent symbol for something else: the country’s deep reliance on Chinese financing for its big-ticket development works and growing uncertainty over the future of its ties to Beijing.

Over the past decade, China has pumped billions of dollars into countries across Latin America, diversifying its own investment portfolio while dipping into the region’s pool of raw materials like oil, iron ore and soybeans. But in Ecuador, the fanfare around China’s presumed role as a financial savior has deflated, giving way to a rising tide of discomfort instead. The refinery's stagnancy has been a reminder that the country has few other options for financial lending outside of China for its future development. But critics say years of Ecuador's dependency on China have left the lion’s share of power and benefits in Beijing’s hands.

China’s appetite for raw materials fueled its trade relationship with Latin America for much of the past decade, but a slowdown in China’s economy in recent years has sent prices of commodities plummeting and stung the region badly. Latin America is now on course to grow by just 0.5 percent in 2015, according to projections by the United Nations. Nevertheless, Beijing is forging ahead with financing major development projects throughout the region, with Chinese President Xi Jinping pledging in January to invest $250 billion in Latin America over the next decade.

However, slower economic growth means Beijing is being more selective about where it puts its money, at a time when Latin American countries are scrambling to fill budget gaps left by the plunge in those commodity prices. That’s left projects like the refinery stalled. It's also strengthened China’s advantage in what critics have described as Ecuador’s unhealthy dependence on Beijing.

Ecuador isn’t the biggest player in the region when it comes to relations with China: Beijing's investments in neighbors like Venezuela or Brazil, at $50 billion and $20 billion, respectively, dwarf the $11 billion in Chinese funds that poured into road construction, mining works and sprawling hydroelectric dams in the tiny Andean country since 2008. But given Ecuador’s size, with a population of less than 16 million and a landmass smaller than the state of Arizona, China’s presence is magnified across the country.

In Ecuador’s northeast, hundreds of Chinese workers are constructing the Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam, the country’s largest-ever project converting the energy of flowing water into electric power. Farther south, Chinese companies are bankrolling and building infrastructure for Ecuador’s first large-scale copper mine in the Amazon. Cheap clothing, cars and electronics made by Chinese companies Chery and Huawei, respectively, all imported from China, are common sights on the streets and and in the storefronts of Quito.

Correa has frequently trumpeted China’s role as benefactor to Latin America. In January, following a historic first ministerial meeting between China and regional bloc Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, he called Beijing’s relationship with the region “one of the most successful development processes in the history of the world, and the most successful in reducing poverty.” Poverty in Latin America declined by 15.7 percentage points from 2002 to 2013, the period when the region’s trade relationship with China was at its peak, according to the United Nations.

But the cost of this economic relationship has given many Ecuadoreans pause, especially as the country lurches into tight financial straits. Ecuador’s outstanding debt to China stands at around $5 billion, at a time when the government, hit by slumping oil prices, has a current budget shortfall of around $7 billion. Payments on Chinese loans will start being due in the next two years, and it’s not clear where those funds will come from. The loans from China were also accompanied by steep interest rates -- around 7 percent on average, which is about twice as high as those from multilateral lenders like the International Monetary Fund.

“It’s true,” said Manta resident Laura Villamar, 25, when asked about criticisms that Ecuador had indebted itself too deeply with China. “China is the ones with the funds, so they offer it and we just take it. There’s no choice but to keep getting into more and more debt.”

Seven years of contracts and loan agreements also effectively give China the rights to around 90 percent of Ecuador’s oil shipments, sparking criticism that the Correa administration has transferred ownership of its most important industry to Beijing.

“When the boom was strong and all these projects were moving forward, people were just psyched about the economic development,” said Matthew Terry, executive director of the environmental organization Ecuadorian Rivers Institute, from his office in the Amazonian city Tena. “The party is now over. More and more people are starting to realize, ‘Oh, look at this, Ecuador has pretty much committed its domestic crude oil production for the next 10 years just to pay loans to China through last year.’”

The great question today is where emerging-economy debts are hiding http://t.co/GHSdsLkpCc pic.twitter.com/1Pn5XNZUje

— Project Syndicate (@ProSyn) October 14, 2015

Some of the fiercest backlash against China’s presence in Ecuador comes from the environmentalist community, which has attributed Ecuador’s continued push in extractive activities like oil drilling and mining to servicing its deepening debt.

Gloria Chicaiza, an activist with local environmental group Accion Ecologica, has focused most of her attention on rallying against the Chinese-backed Mirador mining project in the south, which was the crux of a protest she led at the Chinese Embassy in Quito along with around 50 indigenous women in September.

“Ecuador depends on mining and petroleum more than ever before,” she said. “And never before have we ever been indebted to one single country like we are now with China.”

In addition to threatening the biodiversity of the surrounding area, the Chinese firms running the project had a history of substandard practices when it came to worker and environmental protection, she said. The Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam has also been the target of similar complaints of poor worker safety and ecological damage, attributed at least in part to the Chinese company involved. Last December, a burst pipeline in the hydroelectric dam made a platform collapse, killing 13 workers, most of them Ecuadorean, setting off a flurry of worker demonstrations.

Chinese financing became a crucial lifeline for Ecuador after Correa’s administration defaulted on $3.2 billion in foreign debt in 2008, shutting the country out of foreign capital markets. Correa hailed China’s no-strings-attached loans as a welcome alternative to the International Monetary Fund, whose loans come with conditions aimed at fostering economic restructuring and open markets.

But Chicaiza suggested that the mounting pile of debt to China and complaints around Chinese-backed projects had made it no better alternative to the IMF.

“The reality is that loans from the Chinese government for mining investment don’t comply even minimally with parameters of transparency or social and environmental responsibility that multilateral banks provided for the same type of operations,” she said.

Ecuador’s environment minister, Lorena Tapia, who stepped down from her post last Thursday, previously dismissed complaints that Chinese companies have been allowed to work under lower standards for environmental or worker protection. “We have Argentine companies, French companies, U.S. companies, Canadian companies, Chinese companies operating in Ecuador,” she said, speaking in a boardroom in her ministry in Quito. “Some of them are much better behaved, some of them aren’t. And in the cases where they aren’t, we have already applied sanctions.”

But another slice of discomfort lies in the fact that all the mining, drilling, road construction and digging that has been underway with Chinese funds have essentially gone to making it easier for oil, copper and other raw materials to get shipped back to Chinese markets. Ecuador, in turn, hasn’t been able to shift away from its dependence on oil and boost its exports of finished, value-added products, even though Chinese goods have flowed into the country.

That’s a similar story across the region, particularly in countries like Argentina, Venezuela and Brazil, which have relied more heavily on China’s thirst for raw materials and are now reeling from the plunge in commodity prices.

The short-term benefits of China’s trade relationship with Latin America during the commodity boom are hard to discount, said Kevin Gallagher, director of the Global Economic Governance Initiative at Boston University and an expert on China-Latin America relations. “China was directly the cause of the economic growth in the region from 2003 to 2013,” he said, noting that most governments used those funds to boost social programs and drastically reduce income inequality and poverty in the region. “But in the long run, it sort of locks the region back into its growth model of the 19th century, which it spent 100 years trying to get out of.”

But that isn’t necessarily China’s fault, Gallagher said. “It’s not China’s job to make other countries develop. Latin America sort of squandered the China boom,” he said, adding that many countries failed to boost their savings or develop certain industries to diversify their respective economies.

Regional tensions over Chinese-backed development have been playing out across Latin America, particularly as China embarks on high-profile, controversial infrastructure projects, including an interoceanic canal through Nicaragua and a transcontinental railway in Brazil and Peru, which have already sparked environmental concerns and community protests.

That unease has been giving way to a new phase of realism about China’s relations with Latin America, said R. Evan Ellis, a professor of Latin America studies at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. “In a sense, what you’re seeing in Ecuador with environmental concerns, disillusionment over loans, that’s a piece of a broader re-evaluation of the relationship that’s happening across the region,” he said. “I don’t think it’s catastrophic, but it’s a little bit more realistic. In a sense, the honeymoon is over, and now one has to get down and make the matrimony work.”

Meanwhile, in Manta, not everyone is worried about the country’s future with China. Alex Moreira, a 27-year-old ship worker, waxed enthusiastic about all the benefits the new refinery would bring once it was finally completed. Oil production would surge, fuel costs would be cut, and it would boost per capita income across the country, he said.

“I know with the president’s support, the project will be completed,” he said. “China’s a good ally. Our relationship with them generates revenue, income. For me, that’s the most important thing.”

Brianna Lee reported from Ecuador with support from the International Reporting Project.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.