China Through The Looking Glass: Academic Who Inspired Exhibit Talks About Rihanna’s Gown, 'Orientalism,' And Not Going To The Met Gala

"China: Through the Looking Glass," the exhibition staged by the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute that looks at the influence of Chinese culture on Western fashion, avoided many of the pitfalls such an exhibit could have faced. And it's in no small part due to Homay King, an Asian-American art history professor at Bryn Mawr College, who brought to the exhibition her keen analytical intelligence.

Last year, King, author of "Lost In Translation: Orientalism, Cinema and the Enigmatic Signifier," received a call from the Costume Institute's curator Andrew Bolton, who said he'd read her book and wanted to talk to her about a show the Met was thinking of putting together on China and its influence on Western fashion. Bolton was also the curator of the Costume Institute's 2006 "AngloMania."

"This is important to note," King told International Business Times, referring to detractors of the China show, which runs at the New York museum through Aug. 16. "England, too, can become an object of analysis."

Ideas from their conversations informed, among other things, the exhibit's wall text, helping visitors navigate through the exhibit, and most importantly, alerting them that what they're about to see is not authentically "Chinese," but the product of a traffic jam of references filtered through movies, music and cultural fantasies.

"This exhibition is not about China per se but about a collective fantasy of China," reads the wall text. "It is about cultural interaction, the circuits of exchange through which certain images and objects have migrated across geographic boundaries. Moreover, it points to the aesthetic importance of exploring all the products of our cultural fantasies. As opposed to censoring or disregarding depictions of other cultures that are not entirely accurate, it advocates studying these representations on their own terms."

But wary critics braced for disaster, and seemed almost disappointed not to find it.

Jezebel's Kara Brown anticipated that the Met Gala -- which, of course, is a benefit party extravaganza different from the exhibit -- would be an "Asian-themed sh--show." Refinery29's Connie Wang, although she concluded that the show was "thoughtful, respectful, and fairly thorough," nevertheless seized upon something written in the brochure that she interpreted as suggesting that "Orientalism," literary theorist Edward Said's term for the way the West has objectified and misinterpreted the East, could be "positive." And the New York Times' Holland Cotter had first to say that "it’s all just fashion business as usual" before he could begrudgingly admit that "buried" within the show is "a nuanced historical essay on cultural hybridity, the mixing of styles and ideas over space and time that leaves every culture equal in its impurity to every other culture."

Although a lot of media attention has focused on Beyoncé and Kim Kardashian's Met gala outfits, little has been said about King's participation outside of an allusion here or a brief mention there. International Business Times talked to King about the exhibit, what it felt like to be an academic whose ideas were trickling into a mainstream exhibition, Rihanna's dress -- and how she felt about not being invited to the gala.

International Business Times: How did you get involved with "China: Through the Looking Glass"?

Homay King: Out of the blue last March I got an email from Andrew Bolton of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He said, "We're doing a show about China, but it’s really going to be about images, representations of China from fashion and films. I read your book; can I talk to you?" We talked over email, met a few times, talked about the proposal for the exhibition, which changed many times over the course of its development. We tossed around ideas about which films to include, but mostly talked about ways to frame the exhibition. A lot of the wall text is paraphrased out of conversations he and I had together. (King was also asked to contribute a catalogue essay for the Met's "China: Through the Looking Glass.")

IBTimes: Would you say you were integral to the way the exhibition is shaped?

King: In terms of the framing narrative, absolutely. I think that’s fair to say.

IBTimes: How does it feel, as an academic, to have your ideas blasted out to the mainstream?

King: It’s incredibly gratifying. It’s such an honor. I thought this book ["Lost In Translation"] would have a narrow academic audience and sell 500 copies.

IBTimes: The exhibition makes you aware of yourself looking at things -- through references to artifacts (a modern gown next to a historical garment) and images (clips from movies flicker on screens near the clothes on display). You're reflected in surfaces, you watch other people looking.

King: I was pleased when I saw the exhibition on Monday that the art direction and staging of the show doesn’t just contribute to the spectacle but also to the framing narrative and commentary. When you look at something -- you are going to be reflected. It means that it’s hard to isolate a garment and view it out of context. Whatever angle you stand at, something else is going to be visible and put you in a dialogue with other objects in the room.

King: My jaw dropped. Tears were coming to my eyes. It was so beautiful, sublime, stunning. No matter what critiques or analyses you want to make of the exhibition, it’s hard not to be utterly stunned and speechless when you turn the corner and see, for example, the 1924 Lanvin gown. There were several that brought tears to my eyes. Hearing people saying, "Wow! My god!" That kind of visceral reaction is about the impressiveness of the objects in there – both the couture and the ancient artifacts that are on display. But it’s also a tribute to the staging, which is such a huge part of it.

IBTimes: The show has been accused of trafficking in "Orientalism" but it also serves as a critique of it. Could you define Orientalism?

King: The term is from Edward Said, who used it not about East Asia, but about the Middle East. The primary villain in his work, or object of critique is Western Europe’s relationship to the Arab Islamic world and looking at historians, scholars, art historians. I think we still see this today. There’s a legacy of history writing that treats these cultures as radically other, as if they were being explored under a microscope, and the lens of that microscope isn’t appropriate to that culture. There’s actual distortion and there is, in addition a power relationship and attitude of condescension. That’s the core definition.

With the rise of cultural studies in the '80s and '90s, people started to use it in a looser way, to talk about Western, i.e. American and European, representations, stories about, depictions of Asia, often as a conflated mass of different ethnicities insufficiently distinguished from one another and doing so in a way that is either incorrect or derogatory.

IBTimes: Is there a recuperative way of viewing our love for these fetishized ways of looking at other cultures? To see it as an attempt to appreciate other cultures?

King: I think that’s a nuanced, fine-grained point that I’m worried people aren’t getting in media coverage I’ve read. It’s not to say that Orientalism is cool or that we can recuperate it or do a redemptive reading of it. That’s not at all the message that I had hoped would come across in the show. Rather, it’s about being honest from the get-go that these are inauthentic representations. They don’t aspire to provide document or historical verisimilitude. They are fantasy worlds, they’re about a fantasy version of another world. It’s a different way of getting at that question.

It’s one thing to appropriate or directly steal or copy art from another culture or person, and claim it as their own. Or worst yet to do so with the intention to harm, or to create a harmful image of that culture. But I don’t think any of these objects do that at all. (The one exception might be the Ziegfield Follies clip in the Opium Room!)

It’s not just the intention but the execution. There could be a testament to fascination, curiosity, even reverence. And yeah, maybe reverence of something that turns out to be a figment of your own imagination based on this culture rather than the real version of it. But that’s still curiosity, fascination, and respect, even. It's not about trashing and caricaturing.

IBTimes: Refinery29's Connie Wang quotes from a Met brochure, I think, that says: “We present a rethinking of Orientalism as an appreciative response by the West to an encounter of the East" and she criticizes it as arguing that the exhibition is saying Orientalism can be good.

King: I'm not sure where that's from, but I would revise that slightly and say, the exhibition is not a rethinking of Orientalism. Orientalism is still Orientalism. It’s a rethinking of how you can talk about inspirations that travel back and forth between East and West in a rubric that is not merely Orientalist or merely Western scholars’ appropriating the Near East (what Said is talking about) or Far East with their own lenses, their own preconceptions, etc. That’s what Orientalism is and that’s still bad.

But if you look at that 1924 Lanvin gown -- that’s not someone going in with their own lens and preconception and then saying, "This is China." It’s someone as an artist taking creative liberties with certain motifs, shapes, materials.

IBTimes: It's easy when you walk through this exhibition to want to appropriate the objects: to take their picture, to want that dress. What is it about beauty that invites that uncritical response?

King: It’s a question that a lot of care and thought went into about how to balance that very natural reaction and not necessarily to moralize about it or forbid it, but to put it into a critical context. That was part of the conversation from the beginning. I think about Laura Mulvey’s famous essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." At the end of the essay she concludes visual pleasure is saturated with misogyny. She’s being overtly polemic. Our only reaction, she writes, can be to give up visual pleasure and view its demise with no more than sentimental regret.

It's such a moralizing and impossible edict. There were reasons she said that at the moment; no one was saying that at the time. But we’ve entered a new era. Let’s think about how we can talk about these objects as both sensuous and visually pleasurable, absolutely evocative in a sensual, pleasurable way, and yet we don’t have to deny that or ignore it, in order to also think about the objects, and have an interpretation or other appreciation. This goes back to film theorist Christian Metz, who asks, how can I be a film critic and a cinephile at the same time? Doesn’t the cinephile threaten to overwhelm the critic? Those two things can coexist together.

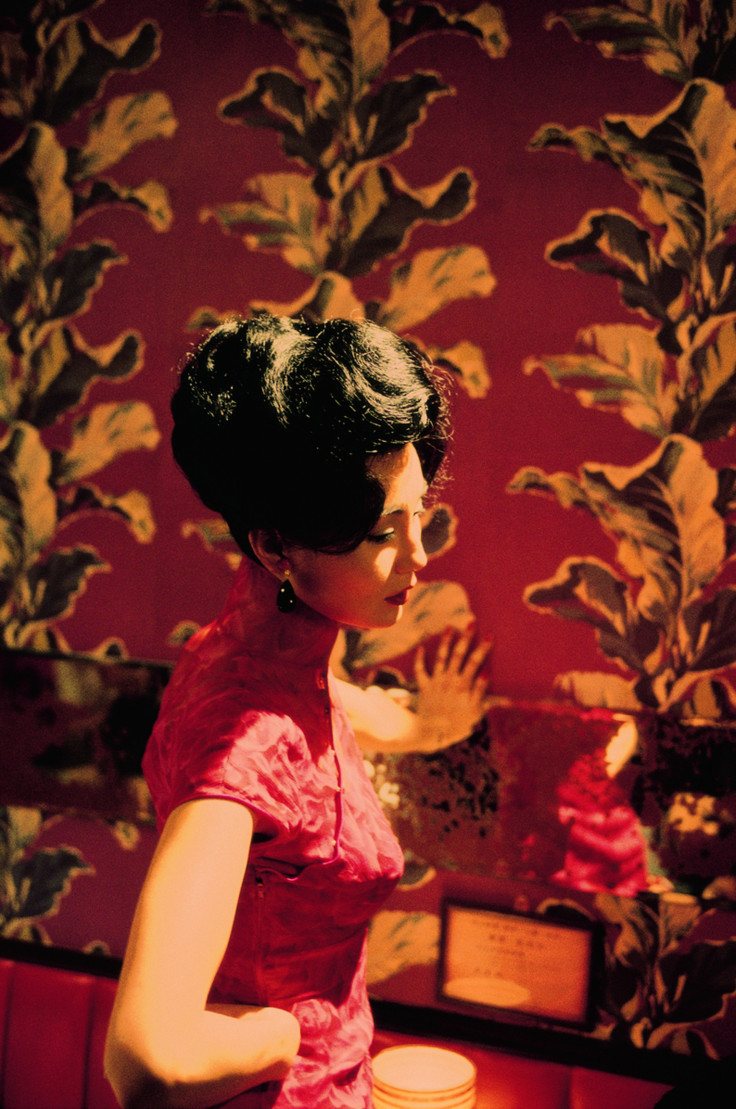

IBTimes: How did filmmaker Wong Kar-Wai ("Chungking Express," "In the Mood For Love") get involved?

King: The Met wanted a Chinese or Chinese diasporic film director to do the artistic design for the exhibition, to make the exhibition somewhat cinematic and to add another layer of commentary, add another voice into the mix. From the start, the show was envisioned as a multimedia one, to take advantage of the capacities of the Costume Institute space, where they can do that.

IBTimes: The music is really interesting too. How did those choices get made?

King: Wong Kar-Wai did the audio design, too. There are some original, quasi-original atmospheric soundtracks. There are a few musical pieces that are direct references, and in a way also commentaries and metacommentaries on the objects in the room. One of those, in the [1920s Asian-American actress] Anna May Wong room, the music is Billie Holiday singing, "These Foolish Things Remind Me of You." It was a song about Anna May Wong written by an ex-lover.

IBTimes: Interesting: In an exhibition about things that remind you of other things!

King: Yes, fantasies you create when you’re at a degree of remove or when the object of fantasy is absent from you. I love the choice [of music] also because it was written by a man who was Anna May Wong’s former lover, about his longing for her. So it’s a reversal of the classic "Madame Butterfly" story, where you have the Asian woman pining away for her European lover who’s left her behind. And it's sung by Billie Holiday.

IBTimes: How do you see Orientalism in the 21st century? Is it morphing? The same?

King: You still see blatant examples of it. This will be my only reference to the gala, the red carpet, and celebrities -- but in the last couple of days, it’s been frustrating when I’ve tried to get reviews and coverage of the actual show. And when you search, everything comes up to the gala! It’s the spectacle component. But this show -- which took over a year and involved many departments at this amazing museum -- the gala and the exhibition are obviously two very different things, and they shouldn’t be conflated. But it's also a symptom: It shows the inability to show distinctions between the costumes in the show and what the guests going to the show are wearing.

IBTimes: You didn't go to the Met gala. Why?

King: It's their biggest fundraiser. They have a limited capacity, and the minimum donation is $25,000. I was not invited. I don’t mind. Not that many people got to go, including some other curators. I would have jumped at the chance, but I’m slightly relieved to have not been in the media circuit.

IBTimes: And speaking of the costumes at the gala -- what did you think of them?

King: I felt bad Rihanna was made fun of. She wore a Guo Pei -- a female, Chinese designer. It’s a dress that is in a conversation with that beautiful gold gown that’s in the Buddha gallery. It wasn’t just kitsch. It was the imperial yellow color with that Qing dynasty imperial yellow. And Rihanna's a queenly figure. It was like performance on royalty, faded dynasties, the legacy of royal pageantry in an era when we don’t have that many royal families.

IBTimes: How is that different from women you see on Halloween dressed up in cheongsams wearing chopsticks in their hair?

King: In that case, you're quoting not just a falsified but a negative stereotype. Are you trying to dress up like a Chinese prostitute who was forced into servitude in the early 20th century? What are you quoting here?

IBTimes: And Sarah Jessica Parker?

King: She was the worst. And I like kitsch in certain circumstances.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.