China’s Economic Growth To Slow As Beijing Curbs Shadow Banking With New Rules

China's getting tough on risky off-balance-sheet lending. While recognizing shadow banking as an indispensable part of the financial market, the country’s cabinet has published new rules aimed at reining in the rampant growth of shadow banking, various media reports said. The move will inevitably drive credit growth lower in 2014. And, as a result, overall economic growth will fall.

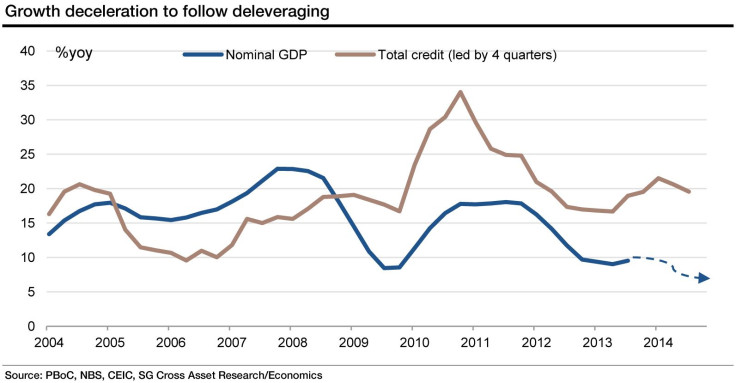

“This development, if confirmed, is yet another strong statement of Beijing’s willingness to de-lever the economy, supporting our below-consensus call for China’s near-term growth, particularly 6.9 percent for 2014,” Wei Yao, analyst at Societe Generale, said in a note.

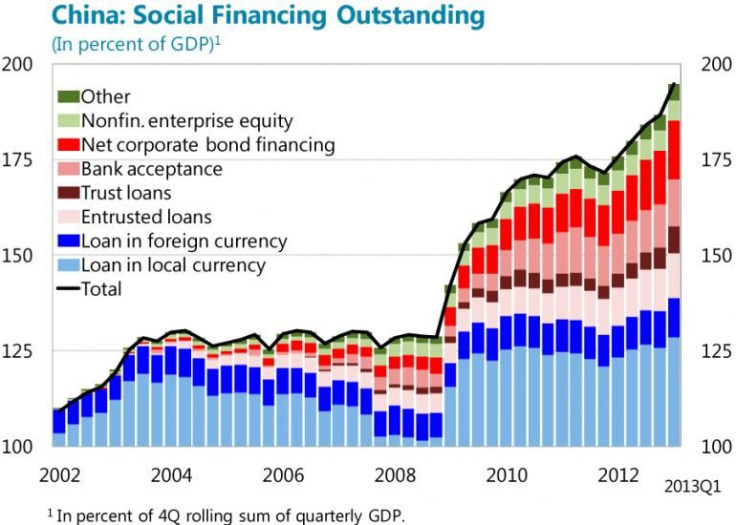

Before 2008, credit was expanding at roughly the same rate as the economy, which means the credit-to-GDP ratio was flat. Since 2008, total credit in the Chinese economy has jumped by 75 percentage points to 200 percent of GDP; by comparison, the rate was only 40 percent before the U.S. subprime bubble burst. Mainland banks are adding assets at the rate of an entire U.S. banking system every five years, according to Fitch.

China's leaders are concerned that the country's economy has become overly reliant on borrowing to fuel growth. They are now willing to tolerate short-term pain in the interest of setting the economy on a more sustainable path.

Shadow banking can take many forms, including loan sharks, investment companies known as trusts and off-balance-sheet lending by regular banks.

The draft rules -- known as Document No. 107 -- were first reported by China Business News, a local newspaper, and seem to have only been given to senior executives at (big) banks at this stage.

“The emergence of shadow banks is an inevitable result of financial development and innovation. As a complement to the traditional banking system, shadow banks play a positive role in serving the real economy and enriching investment channels for ordinary citizens,” the document said, according to a copy obtained by the Financial Times.

“At present, our country’s shadow banking risks are under control overall. But as the 2008 global financial crisis demonstrated, shadow banking risks are complex and hidden, and vulnerabilities can emerge suddenly and spread easily causing systemic problems,” the document stated.

The policy notice identifies three types of shadow banking activities and vows to monitor their development more closely: unlicensed unregulated credit intermediation (such as via online finance companies), unlicensed but lightly regulated credit intermediation (such as via credit guarantee companies and microcredit companies), and licensed but insufficiently regulated financing activities (including those conducted by money market funds, informal asset securitization and some wealth-management businesses).

The People’s Bank of China is said to be in charge of compiling and reporting comprehensive data of shadow credit on a regular basis.

There are a number of harsh rules, targeting a number of major drivers of China’s credit growth in the past few years. For instance, in a notice dated March 25, the China Banking Regulatory Commission said banks must clearly link wealth-management products with the assets that proceeds are invested in. Separately, trust firms will likely face much tighter capital rules when conducting credit intermediation. These two items alone can lead to notable slowdown in credit growth, if implemented strictly, according to Yao.

“The key to a less painful deleveraging path is to divert credit away from the inefficient part of the Chinese economy that is also insensitive to interest rates, such as local governments and some state-owned enterprises,” Yao said.

An official audit released last week showed that China's local government debt reached 17.9 trillion yuan ($2.95 trillion) at end-June 2013, or up from 10.7 trillion at end-2010.

Overall, 43 percent of local government's debt came from nonbank sources. Shadow banking institutions, including trust companies, securities firms, insurance companies and leasing companies accounted for 11 percent of the local government debt. The rest of the nonbank debt is from bonds, individuals and a variety of loan guarantees.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.