China's Stock Rebound Continues As State Media Say 'Confidence Has Been Restored'

SHANGHAI -- Shares continued their rally in China and Hong Kong on Friday, with the massive market-stabilizing measures taken by the Chinese government earlier in the week apparently convincing many investors that all hope was not lost, following a fall of more than 30 percent in the value of local stocks in the preceding three weeks.

Following a rise of more than 5 percent on Thursday, the main Shanghai Composite Index closed 4.5 percent higher. It meant that, after a turbulent week that saw huge falls on Tuesday and Wednesday, the index actually finished the week almost 5.2 percent up.

The rise followed the latest government intervention, which included central bank funding of more than $19 billion dollars to China Securities Finance Corp, which provides margin financing loans to brokerages, according to state media. The Shanghai and Shenzhen markets also announced a cut in transaction fees.

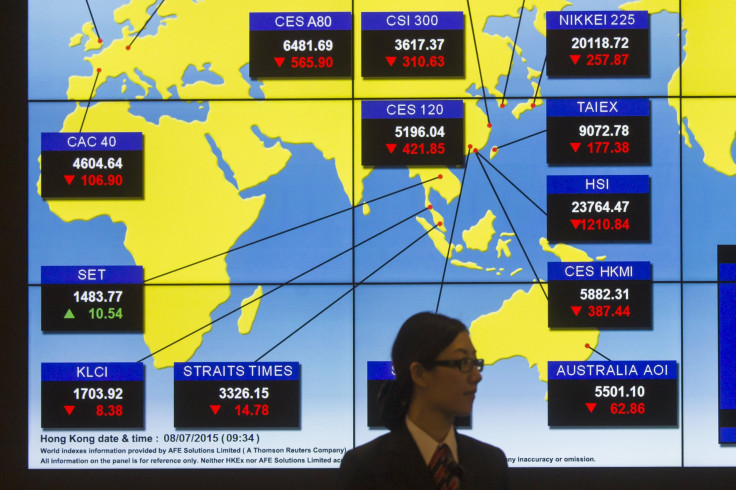

Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index also closed just over 2 percent higher while China’s secondary market and high-tech board in Shenzhen -- particularly hard hit earlier in the week -- were both up more than 4 percent, though they still finished down 3 percent and 2.7 percent respectively on the week.

Official Chinese media were quick to praise the government’s measures, which also included ordering state-run banks, big state companies, and China’s largest brokerages to buy shares -- or at least not to sell until the market had risen significantly. The Global Times newspaper said the moves had restored public confidence in the market.

For some retail investors, that seemed to be the case. At one of Shanghai’s oldest securities houses, Shenyin Wanguo, in a sidestreet near the city center, there were smiles among the mainly elderly investors watching stock prices on big screens on Friday, as the majority of companies rose to their daily 10 percent trading limit.

Janice Li, an editor at a publishing house, told International Business Times that she had bought back into the market on Friday, after selling off much of her holding of some $15,000 in recent weeks as the market began to fall. “The volatility recently has been worrying,” she said, “but it’s the government’s policy to use the markets to develop the economy -- so I still think the prospects are good.”

Yet more than half the companies on China’s markets remained suspended on Friday, having asked for trading in their shares to be halted this week, in an apparent attempt to weather the storm on the markets. And some analysts have criticized the authorities for making it so easy for listed firms to suspend trading -- while others have said that the government’s interventions this week raise questions about its promises to introduce deepening financial reforms.

Andy Rothman, China specialist at fund manager Matthews Asia, suggested that the authorities’ moves to “micromanage a stock market in which 80 percent of turnover is by retail investors” were futile. However, in comments emailed to IBTimes, he said he believed the government would continue with market-oriented liberalization, since it knew that “financial sector reforms are required to support entrepreneurial firms,” and that this was “key to continued economic growth.”

Some observers have warned that the recent upheavals on the markets could damage the relationship between the Chinese government and the country’s middle class, which has accepted limits to political freedoms in exchange for the promise of continued economic development and growing wealth. Kerry Brown, head of the China Studies Center at the University of Sydney, wrote this week that significant losses by the middle classes, on a market that the government has talked up repeatedly over the past half year, could be “potentially calamitous,” and lead to a “crisis of faith” among some of China’s most aspirational and entrepreneurial citizens.

However, Rothman suggested that, at its current level, the knock-on effect on the real economy, and ordinary citizens, should not be disastrous: he noted that China has about 50 million active individual market investors, or 7 percent of the urban population, and as of last year some two-thirds of investors had put less than $15,000 into the market. And he said that while the outstanding margin balance -- money borrowed from banks and brokers to buy shares -- was currently some US$285 billion, this accounted for only about 3.5 percent of the total value of the stock market -- and only about 3 percent of China’s total household deposits.

“Very few Chinese are likely to be betting anything close to their life’s savings,” Rothman said, adding that many investors still remembered the crash of 2007-2008, when China’s market lost two-thirds of its value.

Nevertheless, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of young investors with short memories surging into the market -- more than 12 million new trading accounts were opened in May alone. And even the official Global Times newspaper -- while downplaying the link between the stock market and China’s real economy -- on Friday quoted one analyst as saying the recent falls on the market showed that Chinese investors needed to “learn to invest in a much more measured way,” and another as saying the government should “learn from this experience and launch financial reforms to prevent it from happening again.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.