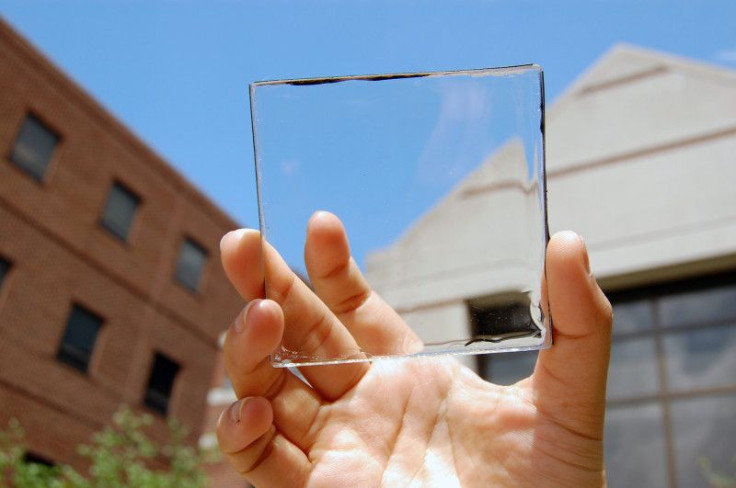

Clear Solar Panel Could Turn Smartphones And Tablets Into Mini Power Plants, Michigan Researchers Say

What if your smartphone or office window could soak up enough sunrays to produce electricity? Researchers at the Michigan State University say they’ve developed a clear panel technology that could do just that.

The “transparent luminescent solar concentrator” module joins a handful of other fledgling see-through solar products that scientists hope one day to bring to market. The idea is to use existing surfaces to generate power, rather than install large arrays of panels on the ground or on rooftops.

“It opens a lot of area to deploy solar energy in a non-intrusive way,” Richard Lunt of Michigan State’s College of Engineering said in a statement this week. “It can be used on tall buildings with lots of windows or any kind of mobile device that demand high aesthetic quality, like a phone or e-reader.” Lunt said his ultimate aim is to make a device so transparent that consumers don’t even know it’s there.

The module, which now looks like a clear glass drink coaster, uses small organic molecules developed by Lunt and his research team to absorb nonvisible wavelengths of sunlight. Researchers can tune the materials to pick up just the ultraviolet and near infrared waves, which then “glow” at another wavelength in the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum, Lunt explained. The glowing infrared light is then guided to the edge of the plastic module, where the wavelengths are converted into electricity by thin strips of solar photovoltaic cells.

The research was featured in a recent issue of the journal Advanced Optical Materials.

Transparent solar technologies are also in the works at research hubs including at Oxford University in England, where scientists are developing a product that could be used in windows. At team at the University of California at Los Angeles has developed a transparent film that can be affixed to buildings, car sunroofs and tablets to generate electricity.

Besides high costs, however, the main challenge facing these and similar technologies is efficiency. Michigan State’s module, for instance, is currently able to convert about 1 percent of solar energy into electricity. By comparison, China’s Yingli Green Energy Holdings Co. (NYSE:YGE), one of the world’s largest panel makers, produces modules that achieve about 15.6 percent efficiency; higher-efficiency models by firms like California-based SunPower Co. (NASDAQ:SPWR) go even higher.

Lunt said his clear solar technology could reach efficiencies beyond 5 percent when fully optimized.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.