Like Cocaine Minus the Risk, Rhino Horn Trade Explodes in Africa

Driven by relentless demand from Asia, rhinoceros horn now fetches some $65,000 per kilogram, or nearly $30,000 per pound, on global black markets, making it worth more than the street price of cocaine. Yet the penalties for trading in rhinoceros horn are barely a fraction of those confronted by convicted drug dealers -- an equation that has dramatically accelerated the killing of the animals and pushed them closer to extinction.

As experts debate how to save the rhinoceros, some argue that legalizing the trade of their horns could increase the supply by prompting people who have hoarded them to put them on the market, driving down the price and dissuading poachers. But others argue that the opposite could result: Legalization would remove the stigma associated with buying and selling the commodity, prompting even more poaching.

“Effectively what you’re doing is legitimizing the criminal acts,” Mary Rice, executive director of the Environmental Investigation Agency, said Tuesday in South Africa, at a conference convened to discuss the issue. "The criminals will be the same people who are the traders in illegal trade."

Trade in rhinoceros horn has effectively been banned across Africa and in most of the world since 1976 under the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which has been ratified by most United Nations member states. But that hasn’t stopped demand from steadily increasing in recent decades. Over the past few years, the market has exploded to satisfy insatiable demand in parts of Asia, especially in Vietnam.

In parts of Asia, rhino horn is believed to boast medicinal properties that can alleviate ailments ranging from mere hangovers to cancer. The horns are made of keratin, a protein similar to what makes up hair and fingernails, without any scientifically proven benefits. Wealthy individuals have been buying whole rhino horns to indicate their status. And such people have been buying more and more.

In 2006, one rhino horn typically sold for about $760. Today, the same horn can fetch more than $57,000. Worldwide, the trade is now worth as much as $9.5 billion annually, according to a report from Dalberg, a development consultancy firm based in Washington, D.C.

Yet even as the rewards of the trade have grown exponentially, the penalties for getting caught have not kept pace, enticing savvy operators into the industry.

“The penalties associated with trafficking rhinoceros horn are not aligned to its value,” the Dalberg report declared, citing one potent example: In South Africa, poachers who are caught are apt to be fined about $14,000 while cocaine traffickers wind up in jail for five years.

In some cases, the lucrative market has translated into heists of horns from rhinos mounted in museums and art galleries. But the main result has been carnage for white and black rhinos across much of southern Africa.

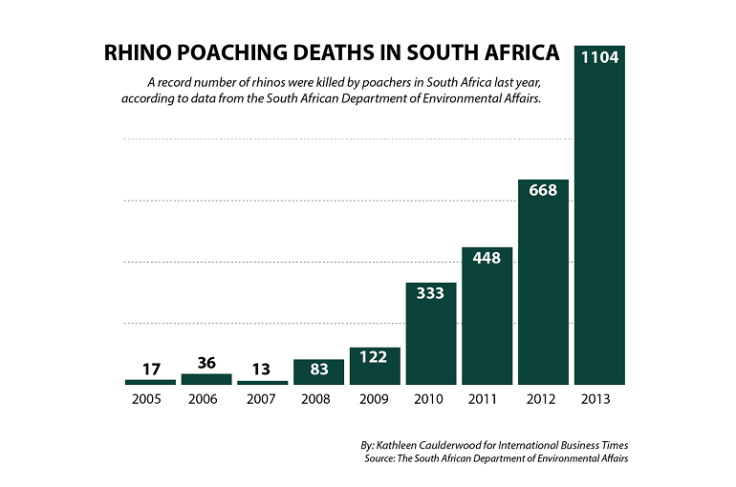

Last year, 1,004 rhinos were killed in South Africa, according to official statistics from the South African Department of Environmental Affairs, a three-fold increase compared to three years earlier.

Some have argued that governments should take on the task of humanely removing part of the horn from rhinos. For about $20 trained workers can sedate and shave the horn without harming the animal, which is a much more reasonable solution, according to Duan Biggs, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Queensland in Australia. He wrote an article in Science magazine advocating for the creation of a “central selling organization” that would mediate between licensed buyers and sellers, while taking a modest fee.

“As primary custodian of Africa’s rhino, the South African and Namibian governments should take leadership to enable serious consideration of a highly regulated legal trade as soon as possible,” he wrote in the article.

But for others in the field, it’s not so simple. Professor Gavin Keeton, economics professor at Rhodes University in South Africa, argues that if rhino horn trading is legalized, it could have the opposite effect of driving prices up, speeding the beasts' extinction.

“There is no way of knowing how much the stigma and fear of being caught buying illegal rhino horn affects demand,” he wrote in September. “Such restraints would disappear by legalizing rhino-horn trade, and demand could soar, outstripping all efforts to increase supply.”

In January, a group called Economists at Large published another study debating the question of legalizing rhino horn.

“The formal studies suggest that predicting the outcome of liberalising trade is complex and difficult to determine,” they wrote. “Although it may decrease pressure on poaching, as rhino horn becomes increasingly supplied through the non-lethal legal trade, there is also a real risk that trade could drive an increase in poaching.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.