Controversial Pension Advance Industry Flourishes With Little Federal, State Scrutiny

When Dr. Louis J. Kroot fell into money troubles and cast about for a way to get some cash quick, an ad in a military magazine caught his eye. A veteran, Kroot learned he could take out an advance on his guaranteed pension and pay the money back with his monthly retirement checks.

But the advance, a $91,566 lump sum, would end up costing far more than a conventional loan. All told, the arrangement would end up costing Kroot and his wife more than $230,000 over 8 years, an effective interest rate of 30.7 percent.

Pension-holders like Kroot, who shared his experiences on the floor of the Senate this week, have increasingly become the targets of controversial pension advance companies. Now consumer advocates are asking why financial regulators haven’t done more to rein in the questionable business practice they label “pension poaching.”

“We need the government to go after this vigorously,” says Karen Friedman, executive vice president of the Pension Rights Center. “When you’re talking about retirement money you need the strongest rules possible.”

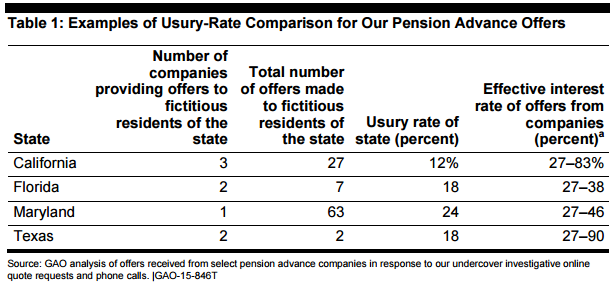

Effectively unregulated in all but two states, pension advance outfits offer lump-sum payments in exchange for a claim on future pension payouts, often from military retirees. As recent reports from the Government Accountability Office have found, the effective interest rates can be astronomical. In California, rates ranged as high as 84 percent, 7 times the state’s legal maximum. In Texas, rates reached 90 percent.

“Whenever there are big pots of money, there will be people like sharks who go after that money,” says Friedman.

But the companies offering the service argue that the advances are not loans. Payments, which the businesses claim do not consider interest, go through escrow bank accounts.

Just two states have passed laws curtailing these operations. In 2014 Missouri became the first state to prohibit pension advances; Vermont regulates the industry but hasn’t instituted a full-on ban. U.S. Rep. Matt Cartwright (D-Mass.) introduced a House bill in 2013 that would address the practice, but it has stalled in committees.

At the federal level, however, as many as nine agencies could claim some oversight over pension advances. As the GAO wrote in a report issued this week, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Federal Trade Commission and Securities and Exchange Commission could all take on consumer- or investor-protection roles in the industry. And agencies like Veterans Affairs and the Defense Department could use their pension oversight powers to regulate advances as well.

Still, as the GAO report found, “There is limited federal oversight of pension advances.”

So far, only the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has taken concerted public action on pension advances beyond issuing warnings. In August, the CFPB filed suit against two companies over unfair and abusive lending practices. (As the GAO had found, the two companies happened to be affiliated.)

And although numerous lawsuits have targeted the practice, some winning millions of dollars for borrowers, advocates say their impact is limited. “Litigation, even when veterans prevail, is an inadequate response to these abuses,” said Stuart Rossman, director of litigation for the National Consumer Law Center.

Rossman cited the case of Daryl Henry, a retired military officer in California who took out an advance to buy a home at an effective interest rate roughly three times what a subprime mortgage rate would be. Henry eventually sued and, with several other veterans, won restitution of nearly $3 million. But the company behind the advances declared bankruptcy, and the winning plaintiffs were left snarled in bankruptcy court.

As the GAO has found, the tangled business structure of the pension advance industry helps it evade regulatory clampdowns. Of the 38 companies examined by the GAO, 21 were in some way affiliated through complex subsidiaries and joint ownership.

“The companies that target veterans for these illegal transactions are elusive,” said Rossman in the Senate hearing. “They change names and websites frequently and use nested structures to hide the identities of the individuals involved.”

Still, Friedman is optimistic that a fractured Congress can manage to push pension protection legislation through. “My guess is on this kind of issue you probably could get bipartisan support -- who could possibly be in favor of predatory lending?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.