Corporate Borrowing Now Flows To Shareholders, Not Productive Investment: Study

Why do companies take on debt? The conventional answer is that they need to invest: to hire more workers, upgrade facilities or invent new widgets. But fresh research shows that in the past three decades corporations increasingly borrow simply to reward shareholders.

“Something is really operating differently in the world of corporate finance now,” says J.W. Mason, an economist and fellow at the left-leaning Roosevelt Institute. “There’s a lot of pressure from shareholders to take every dollar that comes in and send it out the door.”

At the same time corporate debt levels have risen to all-time highs, companies are rewarding shareholders with record payouts. It’s not just dividends. Since 2004, the corporate world has spent $6.9 trillion on stock buybacks -- in which a company repurchases its own shares to drive up stock prices.

How is it that amid stiff market competition and increasing debt loads, companies have found so much money to spend on shareholders?

A new paper by Mason helps explain the trend. Starting in the 1980s, Mason argues, corporate executives increasingly prioritized pleasing shareholders over making the meat-and-potatoes investments of the kind that built the transistor, the 747 and the middle class. As a result, he writes, “Finance is no longer an instrument for getting money into productive businesses, but getting money out of them.”

Mason’s study joins a growing body of research that suggests some of our most basic assumptions about the economy might be off -- or at least woefully outdated. “A lot of our ideas about corporate finance are still based on this older idea of how the world works,” Mason says.

In his paper, Mason compares corporate inflows -- earnings and borrowed money -- with outflows in the form of productive investments and shareholder rewards. In 1960, a dollar borrowed would generate an average 40 cents in additional investment. Since the mid-1980s, the investment per dollar borrowed has shrunk to 10 cents.

Taking the place of investment, he finds, is a correlation between borrowing and shareholder payouts -- an association that was nonexistent before the era of Gordon Gekko. As Mason writes, “Since the 1980s ... firms that borrow the most also tend to be the firms making the largest payouts to shareholders.”

“What’s the logic of borrowing money just in order to pay out shareholders?” Mason wonders. “It’s puzzling.”

In fact, Mason began his research with an entirely different problem in mind. “I was looking for empirical evidence that the financial crisis had played a big role in the fall of business investment.” Instead, it seemed to Mason that it was the goal of rewarding shareholders that hampered business investment.

Few companies exemplify this shift better than IBM. In the postwar decades, Big Blue was an innovation powerhouse, developing some of the defining technologies of the century: the credit card, the floppy disk, the ATM. But with falling revenues in the nineties -- and despite a virtually uninterrupted 80-year no-layoff policy -- the company began letting go what would amount to 180,000 employees in a decade.

In the midst of this turmoil, however, IBM managed to find billions of dollars to pay shareholders. New CEO Louis Gerstner had taken charge, promising “tough-minded, market-driven, highly effective strategies ... that deliver performance in the marketplace and shareholder value.”

Gerstner initiated a program of dividend increases and share buybacks in the 90s. They continue to this day, even amid growing debt and periodic layoffs. Between 2003 and 2012, IBM spent more on shareholder rewards -- $130 billion -- than it earned in revenue. In 2012 alone, IBM issued $34 billion in debt. Its rewards to shareholders that year: $38 billion.

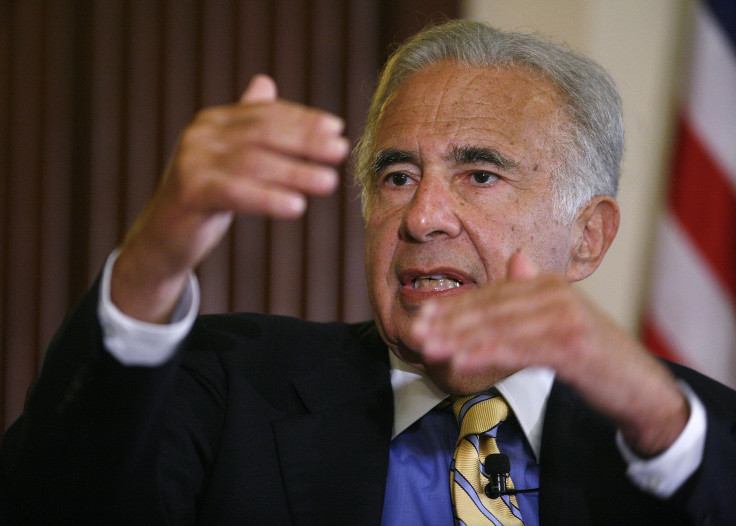

Shareholders generally appreciate stock buybacks, which are seen as a way for companies to make their shares more valuable by decreasing supply. Activist investors like Carl Icahn regularly issue proclamations demanding that companies repurchase shares to bring prices in line with what they think is appropriate. Pressure from Icahn has helped push Apple to award shareholders with more than $100 billion in the past two years.

For orthodox economics, this is a major departure. In the classic economic view, the corporation plows its profits into internal expansion, which brings in more earnings. When earnings fall short, borrowing allows companies to keep operations going. They might take on debt just as you would get a loan for home renovation.

But Mason’s paper demonstrates that the salad days of the American corporation may be over. In the mid-eighties, the “shareholder revolution,” inaugurated by a wave of hostile takeovers, moved the center of corporate gravity from the CEO to the mega-investor. Since then, companies have seemingly concerned themselves more with rewarding their owners than making productive investments.

That home renovation loan no longer goes to buying plaster and drywall -- it goes into the homeowner’s pocket. Only in this case, the homeowners are shareholders, and they don’t live in the house.

The paper isn’t without its limitations. Looking at the economy as a whole, Mason generalizes a diverse economy. “Financial structures are vastly different in different industries,” says William Lazonick, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell and a leading scholar of shareholder rewards. On the macro level, Lazonick says, Mason “makes certain arguments about what’s going on that may or may not be the case.”

Yet Lazonick, who offered comments on the paper before it was published, agrees with its main thrust -- particularly in how it explains the post-crisis divergence of financial health at the household level and in the overall economy. While markets have brushed up against all-time highs and blue chip companies have pulled in record earnings, wages have barely moved.

“It seems pretty clear that the new system is less favorable to any sort of system where the surplus generated by the firm is shared with the workers,” says Mason. In fact, the association between borrowing and shareholder payouts has only become more pronounced in the wake of the great recession.

One of the bigger takeaways, however, might be the paper’s implications about monetary policy. Since the financial crisis central banks, in a bid to stimulate the real economy, have enabled the corporate debt boom by making credit cheaper. But as Mason finds, “firms use cheaper credit primarily to boost dividends and stock buybacks.”

“If the main effect of easier borrowing for businesses is simply to move money out the door to shareholders,” Mason says, “you’re not affecting real activity in the economy.” It’s a message the Federal Reserve might not want to hear.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.