Do Innings Limits Work In Baseball? MLB Working Toward New Solutions

During the dog days of summer baseball, the New York Mets were as hot as they come. But as the Amazins counted up 20 wins in 28 August games -- swapping a one-game deficit for a 6.5-game division lead -- there was a different kind of countdown as well.

Every time starting pitchers Matt Harvey and Noah Syndergaard took the hill, Mets fans must have been torn. On the one hand, the guys are stars. Harvey, 26, won 13 games with the seventh-best earned run average in the National League. Syndergaard, 23, was just a notch below, winning nine games with a 3.24 ERA during his impressive rookie campaign. Harvey and Syndergaard are a big reason the Mets have taken on new life, the team rising to become the city's newfound sweethearts, and whenever they're given the ball New York has a great chance of being competitive.

But every time Harvey or Syndergaard took the mound in the stretch run, they inched ever closer to a predetermined innings limit for the season, meaning New York was forced to carefully maintain its young arms as the playoffs quickly approached. It felt like the now-famous dilemma the Washington Nationals dealt with in 2012, when they shut down previously hurt Stephen Strasburg at 160 innings and were eventually bounced from the playoffs with the pitcher riding the bench.

Innings limits have been a popular way to attempt to curtail pitcher injuries, especially amid a modern surge of injuries to elbow ligaments that require surgery. But innings limits, a growing chorus of experts have said, is a simplistic, catch-all solution to a complex problem that shifts with each individual. And as Harvey, his agent and the Mets tensely negotiated a planned 180 inning cut-off point, the conversation about the strategy took on a renewed fervor. Innings limits have been used for years, but baseball is moving toward a more complex approach, one that monitors individual pitchers while employing advances in technology and research.

A Blanket Solution

With young pitchers especially suffering career-derailing injuries, the thought process behind innings limits is that a decreased workload lessens the wear-and-tear on a developing arm, preventing the fraying that eventually results in a tear of the elbow’s ulnar collateral ligament. But instead of using a relatively arbitrary cut-off point, factors like a player’s injury history, fatigue levels and throwing motion should all go into determining a pitcher’s usage, experts said.

Thomas Karakolis was one of the lead authors of a 2015 study that looked at innings limits and pitcher injuries which concluded, “inning [s] limits alone cannot be used to protect young professional pitchers against the threat of injury.” He said baseball should navigate away from the simple method of injury prevention and toward something geared toward each individual.

“There should be something other than innings limit[s],” Karakolis, a baseball biomechanics expert, said. “But we can’t just jump to the first thing that sounds good.”

Karakolis' study looked at young pitchers in the MLB, attempting to find a relationship between innings pitched and injury rate. The league has seen an epidemic of injuries to pitchers, especially those involving the elbow's ulnar collateral ligament, which often leads to the now commonplace reparative Tommy John surgery. The procedure, pioneered by late-Los Angeles Dodgers surgeon Frank Jobe on the pitcher named Tommy John in 1974, involves taking a tendon from another part of the body and using it replace the ulnar collateral ligament.

Some 15-20 MLB players typically get the Tommy John every year, but more have gone under the knife over the past few seasons, with 31 getting the procedure done in 2014. Overall, a full 25 percent of MLB pitchers have had Tommy John. The most common measure taken to mitigate the risk of having a young star shelved for a year to recover from an ulnar collateral ligament injury and the resulting surgery is to ease their workload, sometimes through a game-by-game pitch count but typically through a year-long cap on innings.

Yet Karakolis' study found both "no significant correlation" between innings pitched and future injury and no relationship between a year-by-year increase in work and future injury. Limits alone aren't the lone answer, the study found, Karakolis calling it a "blanket" solution to a complex problem.

It's unclear exactly when or how innings limits took hold, but the most significant shift toward more rest for pitchers took place in the 90s. In the 70s especially and into the 80s, workhorse pitchers would regularly throw complete games, pushing physical limits to go the entire nine innings. Pitchers would lead the league in innings pitched by throwing around 300 to 350 innings. Clayton Kershaw led the MLB in 2015 with just 232.2 innings pitched.

It took time, but MLB teams realized heavy workloads could run arms ragged. Data began to present itself. Sixteen years ago baseball writer Tom Verducci wrote, for instance, about the "year after effect," which promoted a model of slow growth in workload for young pitchers. Around the same time, Baseball Prospectus' Rany Jazyerli developed the pitcher abuse points (PAP) metric, the first real data-driven attempt at measuring how each game affected pitchers' arms. Teams began to exercise caution and the simplest method was innings limits. The issue took on a new life in Strasburg's case and re-entered the national conversation with Harvey.

Where Injuries Take Seed

For Dr. Glenn Fleisig, the problem begins where MLB careers take seed: youth leagues. Fleisig has spent much of his career studying pitchers' arms as the research director at the American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI). It's the place headed up by Dr. James Andrews, a surgeon so prominent fans know him by name, who has been at the forefront of most of the work done looking into ulnar collateral ligament injuries since 1987.

A common misconception of ulnar collateral ligament injuries is that is happens explosively. Fans see video clips of a pitcher suddenly grabbing his arm after a single throw, and assume it was freak-accident that happened in a split second. In reality, small tears often build up over time, beginning in Little League, with the straw breaking the camel's back when the pitcher reaches the majors. A youth game in which an irresponsible coach leaves "Little Billy" on the mound too long to win the 12-year-old championship can contribute to an injury years down the line.

As time went on, Fleisig noted he was seeing that "more high school age pitchers were getting adult injuries," with the number of youth pitchers undergoing ulnar collateral ligament surgery at ASMI rising sharply from the '90s into the 2010s. In 1995, just 10 percent of ASMI surgeries were on youths. By 2011 that had risen to 23 percent, with the figure hitting a high of 32 percent in 2008.

"Major league pitchers already have the damage in their arm," Fleisig said. He pointed out that ligaments or tendons that tear don't look like a clean snap, they're frayed like old rope, indicating a slow-building injury.

But while a buildup of tears can affect a major leaguer, the most common reason pitchers suffer injuries is simple and, in many ways, commonsensical. "A pitcher who is fatigued and keeps pitching … they’re the ones who are going to get injured," Fleisig said. Increasing strain on an already worn elbow pushes the ligament toward a tear, and creates a hard-to-stop cycle of damage. If an elbow doesn't sufficiently recover from repeatedly chucking a ball 90 miles per hour, it is far more likely to get injured.

It would seem then that innings limits, or pitch counts, would make sense. And they do, but only as one tool in an arsenal. Arms aren't like guns, Fleisig said. Pitchers don't have a certain amount of bullets -- or throws -- until the chamber is empty and the arm goes kaput. Arms have to be managed, each pitcher monitored for his distinct situation. For instance, Fleisig noted, two pitchers can be the same height and weight, throw the same velocity and pitch the exact same amount. Yet one pitcher's arm could be under far more stress because his throwing motion is hard on the elbow.

"Science does not suggest there should be hard and fast pitch counts at any major league level," Fleisig said, adding that instead such limits should be used as guidelines for monitoring a pitcher's workload throughout a season.

Building The Arm Up

If throwing expert Alan Jaeger, a 25-year veteran who has worked with a handful of MLB teams, had his way, then baseball would go back to the days of emptying out a bucket of balls and simply letting the players throw as much as feels natural. With conservative methods like innings limits having taken hold, pitchers arms have grown weaker and are not properly conditioned to stand up to stress because of over-conservatism in training programs, he said.

"Forty years ago [throwing] was based on instinct and you just did what you did," Jaeger said. "[Conservative throwing programs] sound good because they say we’re saving the arm, but it's actually creating atrophy … its doing the opposite it's starting to deplete."

Researchers historically pushed for these lessened workloads, although most no longer think that innings limits alone work. With time, teams listened in order to protect pitchers worth millions of dollars. In short, pitchers threw less. Squads began relying more on specialized relief pitchers -- for instance, a set-up man who typically throws just the eighth inning -- and starters threw fewer innings. To Jaeger, as pitchers began throwing less in games, and also in practice, their arms began to weaken and the injury count shot up.

Jaeger would rather pitchers throw more, like the old days. But that takes some building up of the arm. Jaeger works with pitchers to construct a throwing program specifically for them. He works pitchers toward throwing longer distances in practice and putting more arc on the ball instead of beaming line-drives. And some of the players from 40 years ago seem to agree with him that methods have skewed too conservative.

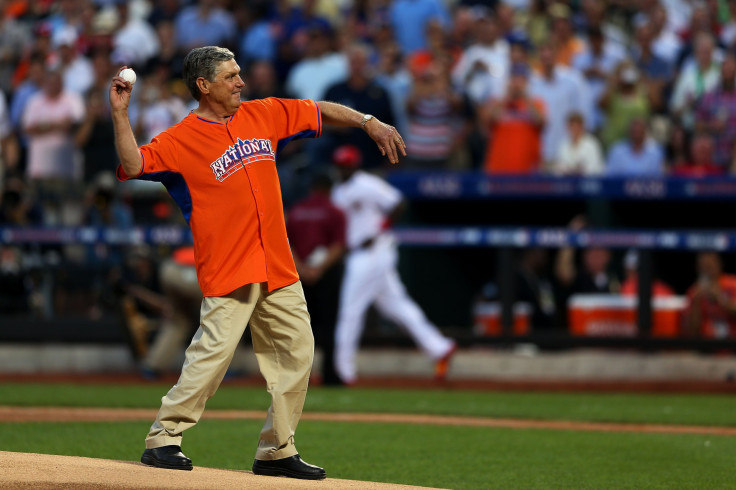

Former Mets pitcher Tom Seaver, a Hall of Famer who pitched from 1967-1986, has said the new, young Mets stars like Harvey and Syndergaard are pulled out of games too early and too often because modern research dictates so. It ends up hurting the pitcher and the team, he said.

“When I’m looking at the numbers of innings pitched and they’ve taken these guys out too quickly, that’s the worst thing. It is so obvious. The computer has won this fight," Seaver said in July, according to the New York Post. “If you are going to build a stud muffin, you leave him out there. You want to get 100 percent of him, you don’t want to get 80 percent of him."

In other words, if you want a star to be worth the hefty price tag of a top contract, build him up through repetition. A mindset like Seaver's or Jaeger's may seem to contradict some of the points made by researchers. But there is overlap, as well.

“I would just say the number one rule of treating an arm is you have to adapt to the individual player," Jaeger said.

A Guessing Game

Seaver himself threw an average of 250 innings per year over two decades of baseball, while modern pitchers are often limited to well under 200 innings per year. Seaver's average year would have easily led the MLB in 2015. Fans or pundits often point to this type of workload to prove arms can take more work. Rick Peterson, a pitching expert with the Baltimore Orioles who previously worked with the Moneyball-era Oakland Athletics, pointed out that these examples are outliers compared with normal pitchers.

"When people try to talk about back in the day … and they start talking about [Hall of Famer Bob] Gibson, [Hall of Famer] Nolan [Ryan]. Everyone they mention, they’re all Hall of Famers," he said. "Nobody’s mentioning the fourth starter, the fifth starter."

Very few modern pitchers could seemingly last on a Seaver-esque workload. Some may be able to work up to it, but teams are no longer willing to risk an arm to find out. What the game is working toward is a happy medium of sorts: where pitchers both build and maintain enough arm strength but avoid the fatigue that can lead to catastrophic injury. ASMI's Fleisig said he thinks organizations have started to move away from over-conservatism and more toward a middle-ground.

What also appears to be on the horizon for baseball is to use technology and careful monitoring to build better programs for individual pitchers. The goal is to figure out the proper workload for a pitcher and keep them on a regulated, comfortable schedule. Technology can also help fix mechanical flaws. A sound delivery in a pitching motion eases the stress placed on an elbow, and advances in technology are working toward measuring the force of each pitch thrown. A number of experts, for instance, name-checked a company called Motus that has developed a compression sleeve to measure the forces placed on an arm while pitching.

Peterson already films pitchers to carefully study a number of biomechanical measurements. "My guess [is] 3 to 5 years, they’ll have sensors all over the body," Peterson said of pitchers. That way, hitches in a delivery can be ironed out.

Further, MLB and ASMI have partnered on an elbow task force of sorts, and are currently operating a study monitoring young pitchers as they enter the league then tracking them for five years.

For a young pitcher like the Mets' Harvey, who has already undergone Tommy John surgery, experts agree he should build back up before jumping into the fully into the fray.

As the 2015 season wound down, the Mets and Harvey eventually agreed on a lessened workload through the final stretch of the season, the star pushing just past 180 innings pitched at 189.1. New York also expanded their rotation to allow the pitchers to get more rest. Syndergaard ran up right against the limit, when his minor and major league duties were combined. All told, the half-measures taken to avoid the cut-off limits worked. The Mets won the National League East for the first time since 2006. They'll play the Los Angeles Dodgers in first round of the National League playoffs, the first game scheduled for Friday.

But for now it's still anybody's guess exactly how to handle a young arm like Harvey's. His agent worked to pump the brakes, and Harvey pushed for more time and the franchise searched for a middle ground.

Most experts agree that the game needs to take care of young arms. But innings limits have proven an imperfect measure. The hope is that soon, for pitchers like Harvey, it won't be such a guessing game.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.