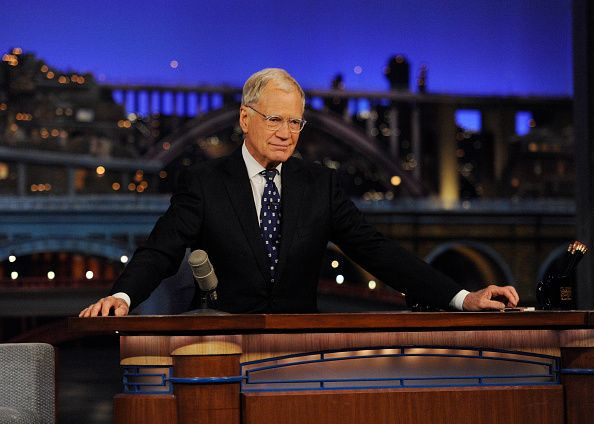

Don’t Get David Letterman? Maybe It’s Generational: Legacy Lost On Many Who Missed NBC’s ‘Late Night’

Maybe every generation gets the late-night host they deserve. If Jimmy Fallon’s earnestness and cheery skits are apt successors to David Letterman’s cynicism, irony and subversive humor, it’s at least in part because of the cyclical nature of cultural luminaries. Letterman, of course, is retiring this week after 33 years in late-night television, a genre he redefined in the 1980s. On NBC’s “Late Night With David Letterman” -- which aired at 12:30 a.m., after “The Tonight Show,” from 1982 to 1993 -- the self-deprecating Midwesterner breathed new life into a format that, after two decades of Johnny Carson, had grown to take itself a little too seriously.

“It was counterculture, counter the establishment,” Tim Brooks, a television historian who worked at NBC as a researcher in the 1970s and ‘80s, said of Letterman’s original late-night gig. “That really set him apart in an era of Merv Griffin and the kind of straight-ahead talk shows with their usual parade of A-listers touting their latest projects.”

But it’s been more than two decades since Letterman himself became the establishment, moving the show to CBS and into its current incarnation, “The Late Show,” and its 11:30 p.m. time slot. For a generation too young to remember an era before cable, Letterman may simply be seen as that moody, old talk-show host who competed with Jay Leno for all those years. Recognizable? Sure. Innovative and edgy? Hardly.

Brian Abrams, a journalist and author who interviewed dozens of people associated with NBC’s “Late Night” for an oral history of the show, said that younger generation may be having a hard time understanding why Letterman’s retirement is getting so much attention.

“Nobody has any idea,” Abrams said. “When I was doing reporting on this story, and I was talking to my friends about it, any friend under the age of 38 had no idea what the hell I was talking about. They were like, ‘Good for you for getting paid work.’ ”

He added, “Everyone over 38 was like, ‘Oh, my God, that’s awesome. Letterman’s the best.’ ”

I guess I'm too young, but I don't "get" David Letterman, or why him leaving is such a big deal

- Clay Kiesling (@TexasDeltaSig) May 16, 2015A Legacy Hidden

Part of the reason younger people may be unaware of Letterman’s influence is that, for many years, evidence of it was almost impossible to come by. NBC never released “Late Night” after Letterman’s defection to CBS. Abrams said the master tapes are rumored to be warehoused somewhere in New Jersey, and many of the episodes have never been digitized.

Brooks noted that the show was produced on a very low budget, at a time when few TV shows outside of sitcoms and procedurals had a second life after their original air date. “There wasn’t perceived to be much value in old product on television,” he said. “It was like, ‘Who cares about this stuff? TV is a medium of today.’ ”

After more than a decade of dormancy, some episodes of “Late Night” are viewable again thanks to the magic of YouTube, but in an age of infinite media choices, it’s hard to place them within the context of their original era, when cable TV was in its infancy and the Big Three networks were still largely responsible for almost all of our home entertainment.

“All that was on, as far as late-night, was Johnny Carson,” Abrams said. “Letterman let the air out of this kind of sense of phony Hollywood in a way that I think that younger viewers were kind of craving.”

At the same time, other intuitions that had been subversive just a few years earlier had begun to show signs of aging. “ ‘Saturday Night Live’ was terrible,” Abrams said. “Lorne [Michaels] had left for like five years, and the show went to hell.”

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow

Talk shows, like news programs, are a genre of immediacy, and hosts fade quickly from our collective memories once they leave the air. If the impact of Letterman’s groundbreaking early work is destined to be marginalized by anyone under 35, he will have followed in the footsteps of innovators who came before him.

“Letterman was a descendant in a way of Ernie Kovacs and Steve Allen and even adopted some of Allen’s gags that he did back in the ‘50s,” Brooks said. “There was a subgroup of comedians -- either variety-show hosts or talk-show hosts -- who really pushed the envelope a lot more and exploited television.”

Asked what he thinks will happen to late night in the post-Letterman era, Abrams said he has no idea. But he speculated that the next David Letterman -- the next true envelope pusher -- will not be working within the confines of the model as it currently exists. “Seth Myers is not going to be the rebel to do it, and TV is probably not the medium that’s going to do it,” he said. “Wherever this revolution is going to be, I don’t know.”

By comparison to those working in the overcrowded media environment of the 21st century, Letterman had it easy. All he needed to do was stay up late enough and wait until the old folks fell asleep. “It’s so funny how just one hour in scheduling difference gives you 20 years of difference in the audience,” Abrams said. “Whoever was nodding off to Johnny at 11:35 wasn’t watching at 12:30, when Letterman was on. People were up. They were on their third beer.”

Christopher Zara is a senior writer who covers media and culture. News tips? Email me here. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.