Earth had Two Moons Until They Collided: Claim Scientists [Photos]

Earth once had two moons a small second moon until the two moons got smashed into each other to create a big lunar body.

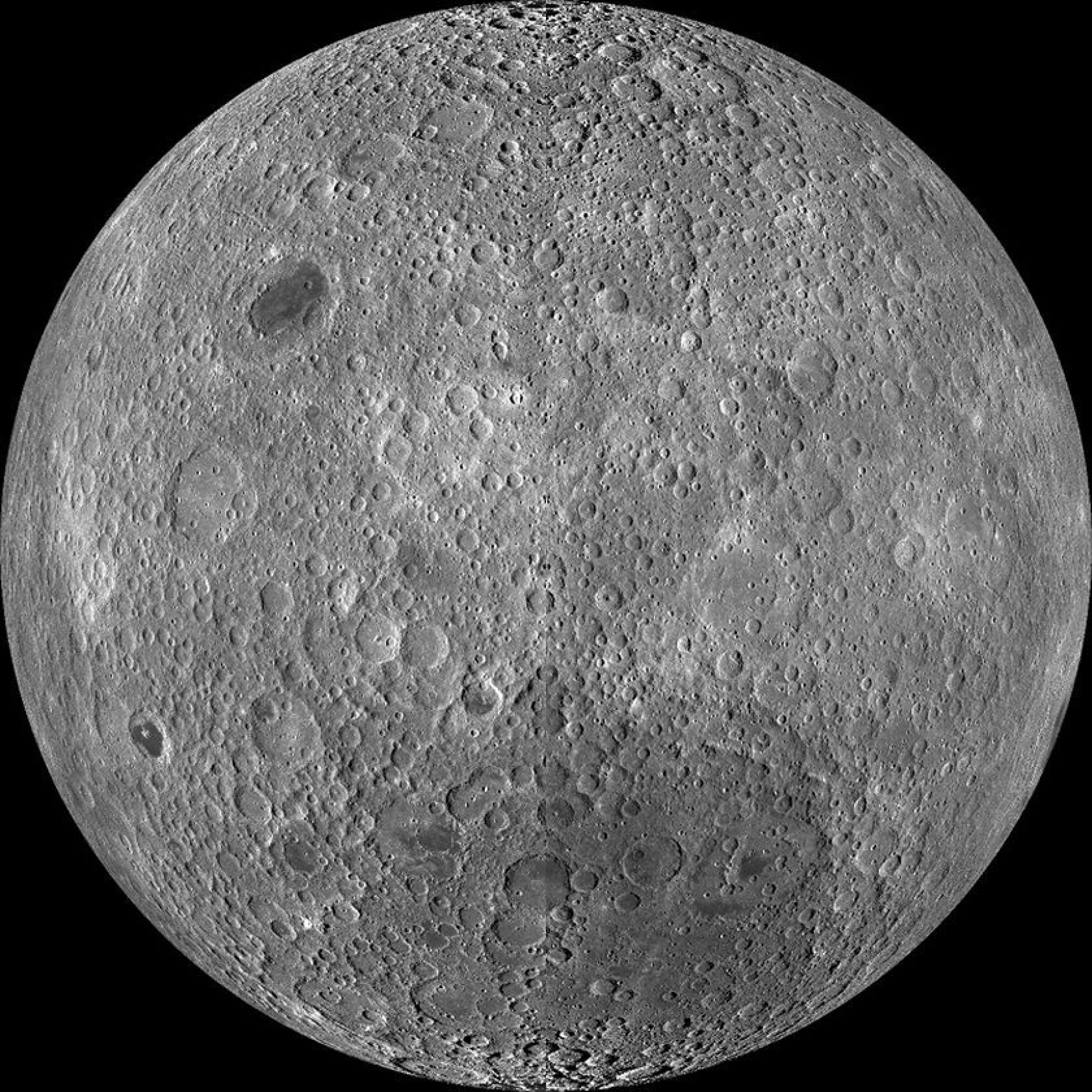

The collision of two moons might explain why the two sides of the lunar body are so different from each other, a new theory suggests.

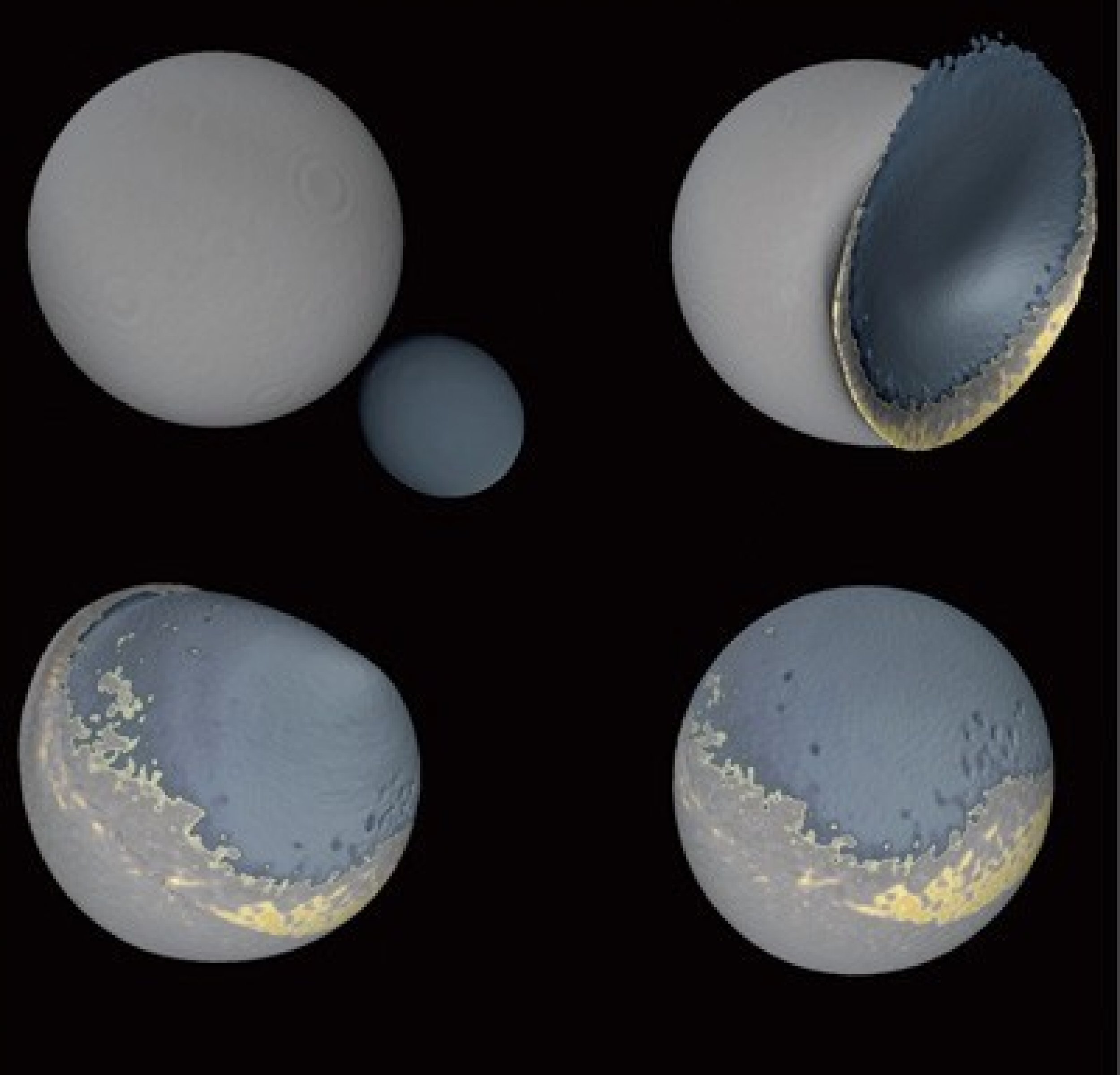

The Earth might have been circled by the two moons in the same orbit until a slow-motion collision that merged the larger object with a sister satellite one-thirtieth its mass more than 4 billion years ago, which created a lunar body that we see today.

Erik Asphaug, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and his colleague Martin Jutzi of the University of Berne wrote an article about the creation of the moon, which was published in the journal Nature.

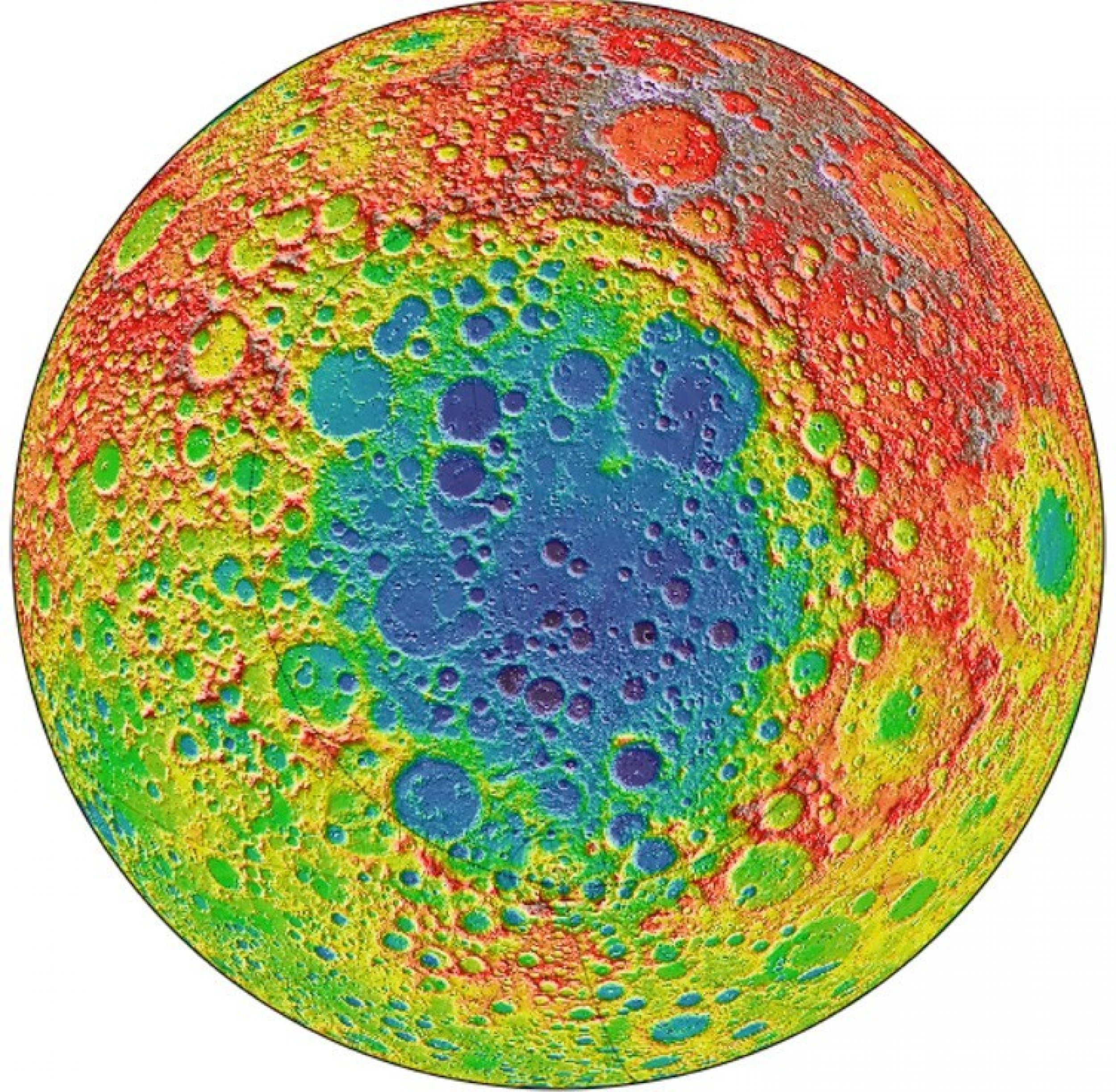

Scientists for decades have been trying to understand why the one side of the Moon which is visible from Earth is flat and is comprised of low-lying plains while the other side which is rarely-seen is heavily cratered and has mountain ranges higher than 3,000m.

But the difference in our planet's moon goes beyond its outer layer, for the crust on the far side is about 50 kilometers thicker than that on the nearside.

Erik Asphaug calls this collision the "big impact" and believes that it resulted in debris pan caking the bigger moon. The smaller moon was the lightweight when compared to its sibling that was three times wider and 25 times heavier with a strong gravity.

"They're destined to collide. There's no way out. ... This big splat is a low-velocity collision," Asphaug told CBS.

Asphaug said after about 100 million years of cohabitation the crash happened at more than 5,000 miles per hour, and that the smaller moon was more than 600 miles wide. It took hours for the rocks and crust from the smaller moon to spread over and around the bigger moon without creating a crater, and a faster crash would've caused the opposite.

The crash occurred about 80,000 miles away from Earth and about a third of its current 250,000-mile distance from the moon.

"By definition, a big collision occurs only on one side," Asphaug told Nature, "and unless it globally melts the planet, it creates an asymmetry."

Many theories on how the asymmetry happened have been offered, but no solid conclusion has been made.

Planetary scientist Alan Stern, former NASA associate administrator for science, told CBS that the theory is a "very clever new idea," but one that is not easily tested to learn whether it is right.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.