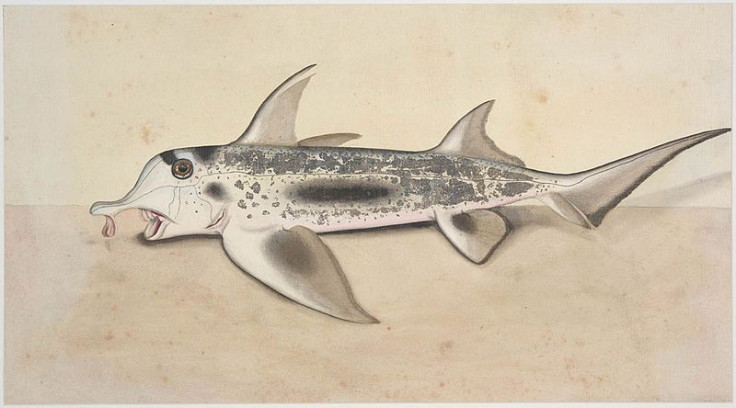

Elephant Shark Like A ‘Living Fossil’; Callorhinchus Milii Hardly Changed For 400 Million Years

The elephant shark, a fish with a trunk-like snout found in the waters off southern Australia and New Zealand, is like a “living fossil,” its genome hardly changed since it first evolved 400 million years ago. That’s according to scientists who recently sequenced the shark’s genome, making it the most primitive jawed vertebrate to have its DNA analyzed.

A new study published online in the journal Nature suggests that the elephant shark, scientific name Callorhinchus milii, is the slowest evolving of all known vertebrates. Like other sharks, the elephant shark has vertebrae made of cartilage, not bone. Researchers from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research in Singapore, who sequenced the elephant shark’s DNA, say the discovery could help researchers better understand how bones formed over hundreds of millions of years.

“Here we report the whole-genome analysis of a cartilaginous fish, the elephant shark,” the authors wrote. “We find that the C. milii genome is the slowest evolving of all known vertebrates, including the ‘living fossil’ coelacanth, and features extensive synteny conservation with tetrapod genomes, making it a good model for comparative analyses of gnathostome genomes.”

The elephant shark isn’t really a shark at all. Rather, the large-snouted marine animal belongs to a group of fish called ratfish, which diverged from sharks about 400 million years ago. Scientists have called this group of cartilaginous fish “perhaps the oldest and most enigmatic groups of fish alive today.” Earth’s earliest fish species paved the way for bony skeletons, a sophisticated immune system and jaws.

Callorhinchus milii grow to around four feet. Elephant sharks, which occasionally get snagged in commercial fishing nets, typically live at depths of up to 650 feet. The fish spends most of its time on the ocean floor, where it rummages for crustaceans.

The fact that the elephant shark’s genome has stayed relatively unchanged means it boasts a genome very different from the genomes of vertebrates today. Scientists say this offers an extraordinary look into the evolutionary past of Earth’s vertebrates.

"We now have the genetic blueprint of a species that is considered a critical outlier for understanding the evolution and diversity of bony vertebrates, including humans," Wesley Warren, an associate professor of genetics at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, told AFP.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.