Fast Food CEOs Make The Most Relative To Their Average Employees, Study Shows, More Than In Retail, Media Or Construction

Shantel Walker has been working on and off for Papa John’s pizza since she was in high school. The 32-year-old New York City resident says that over her 15 years at a Brooklyn outlet of the Louisville, Ky.-based pizza chain (NASDAQ:PZZA), she’s received only two raises that weren’t mandated by federal or state minimum wage hikes. Today she makes $8.50 an hour, 50 cents above the New York State minimum wage, but her employer doesn’t currently use her more than 24 hours a week.

At the top end of the Papa John’s pyramid, CEO John Schnatter, the 51-year-old founder of the pizza chain, received a 26-percent increase in his base salary, to $900,000, according to a recent regulatory filing. His total compensation package last year: $2.1 million.

That income disparity between high-level executives and average employees is more extreme in the fast-food industry than in other areas of the service economy, according to a report released Tuesday by Demos, a liberal economic policy think tank. The study suggests that creating instability among large numbers of employees by not paying them enough to cover the cost of living creates a climate that can be detrimental to shareholder interests.

Income disparity has become a major economic and political issue in the U.S. in recent years as more attention is being paid to what corporate compensation committees give their top executives every year in industries that rely heavily on employees who earn so little that they rely on public assistance programs like food stamps and Medicaid to survive. “I don’t even think this is not fair; I know it’s not fair,” said Walker, who, like many working Americans in the hospitality, food services and retail industries, needs food stamps to eat. “We can’t afford the daily necessities we need to survive in this city. Right now I’m basically catching up on life, catching up on my bills.”

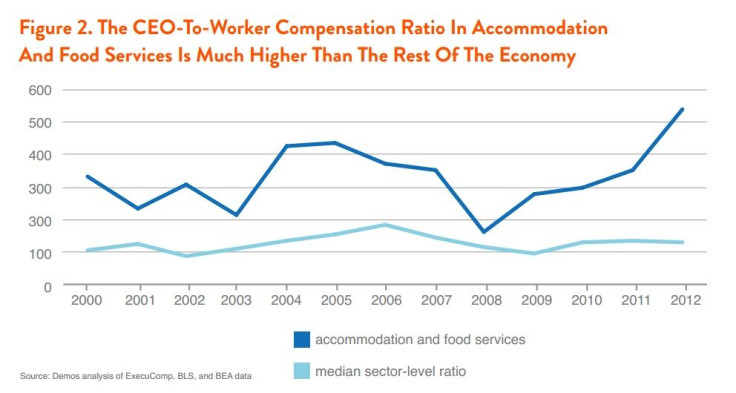

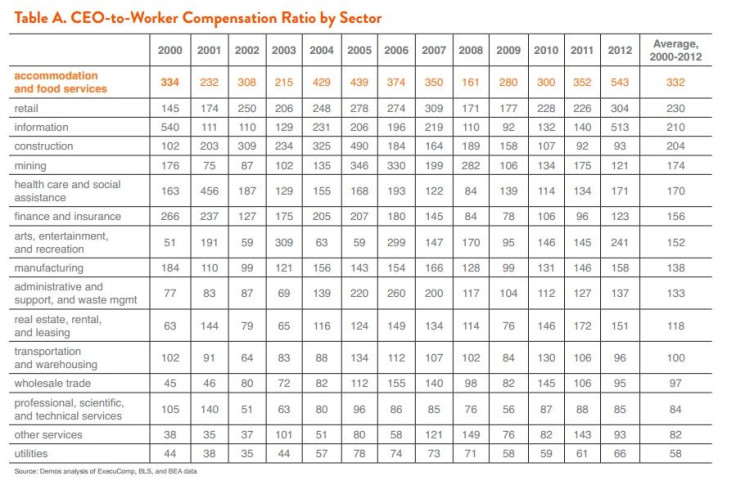

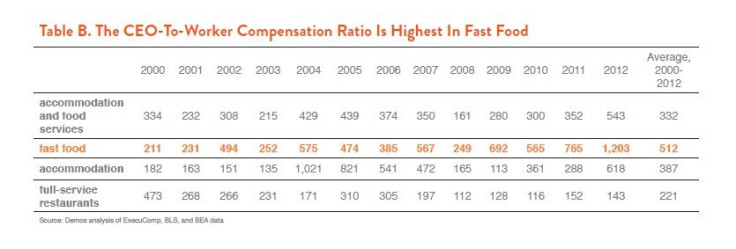

Catherine Ruetschlin, a Demos policy analyst, examined the compensation packages of publicly listed companies in various industries between 2000 and 2012 and found that the large, publicly listed companies in the accommodation and food services sector led in the disparity between what top executives make in salary, bonuses and stock-based compensation, versus what their average workers earn.

While it’s not surprising a sector that employs so many low-wage earners would have one of the greatest disparities between CEO compensation and the typical employee, the data show the gap is notable even by service-sector standards.

“We found that the accommodation and food services sector is a clear outlier over the period,” said Ruetschlin. “It exhibited the highest CEO-to-worker compensation ratio out of all sectors in the economy.”

The average CEO-to-worker compensation ratio for accommodation and food services for the 12-year period was 332 to one, meaning for every $1 an average fast food worker earns the CEO makes $332. In retail, another sector that relies on low-wage hourly workers, the ratio is 230-to-1, closer to the 220-to-1 found in the media and information sector and the 203-to-1 in construction. The disparity between what a CEO earns and what a typical employee of the company makes is even more overt by separating out fast-food from the accomodation and food services sector. In 2012, that ratio was 1,200-to-1.

“This relationship between extraordinarily high CEO compensation in fast food and low stagnant earnings for everyone else is causing strains in firm performance and will be an increasing concern to the economy and to investors,” said Ruetschlin. “Worker strikes, operational issues and legal battles have increased risks for investors in the fast food industry.”

The White House and many Democratic lawmakers are pushing for an increase in the minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 an hour to help reduce economic inequality. Meanwhile, 21 U.S. states currently have wage floors higher than the federal mandate; 13 of them increased their wages at the start of the year.

Leading Republicans and free-market think tanks such as the Cato Institute and the Employment Policies Institute argue that mandating pay increases is detrimental to low-wage workers because it discourages companies from hiring more workers.

Michael Saltsman, the research director at EPI, called the Demos study a “publicity stunt” aimed at building support for the federal minimum wage hike. His group proposes that instead of raising a mandated wage floor, Congress should expand the number of low-income earners who qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit, which increases the income tax refund many poorer working Americans receive.

“If we can acknowledge that the goal is to provide assistance for single parents or childless adults who are currently left out of the benefits package provided by the Earned Income Tax Credit, I think Democrats could get a surprising number of Republicans on board with that,” said Saltsman. “That’s not an inexpensive fix, and I think there would be a robust debate about that, but I think you could get bipartisan support for that.”

Meanwhile, as the debate over how much is the right amount to pay a person for an hour of his or her labor continues among salaried think-tank advocates, Walker is trying to figure out how to get to work for her 24-hour-a-week shift making $8.50 an hour.

“I can’t even afford a Metro [subway] card,” she said.

Read the Demos report here.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.