FDA Is Cracking Down On Added Sugars: How Will Big Food Companies Respond?

Americans spread it on their toast, sprinkle it on desserts, pour it over salads and gulp it down at Starbucks. Sugar is everywhere in today's food supply, yet it’s linked to a host of health problems, including heart disease, obesity and tooth decay. Lately, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has adopted a stricter tone on sugar in food, but it's unclear to what extent the agency's latest proposals will inspire food companies to change their sweetest recipes.

A few companies are charging ahead with revisions to iconic products, but much of the food industry remains stubbornly opposed to the agency's attempts to reduce the generous helpings of sugar found in countless products in American cupboards.

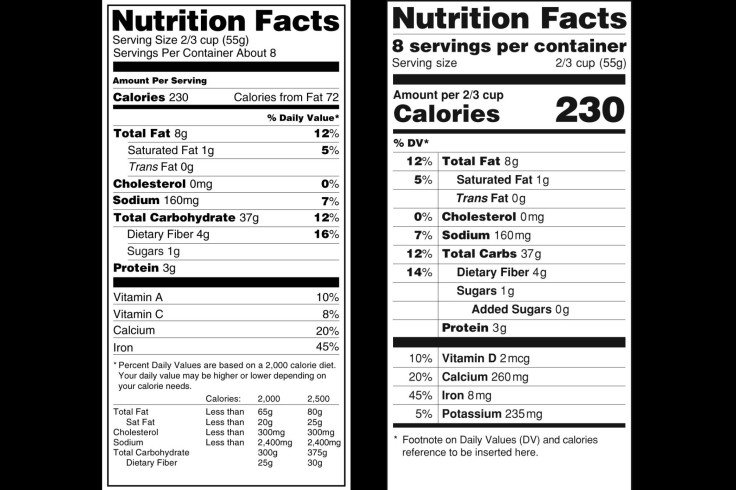

Some sugars occur naturally in foods such as fruit, while others are poured or mixed in to treat consumers’ taste buds to a more satisfying experience. Today, the average American consumes 115 grams of added sugars a day. The FDA is particularly concerned about those added sugars, suggesting a limit of about 50 grams a day for consumers and proposing a rule that would require companies to list them separately on nutrition labels.

“They're basically saying that your daily added sugar intake shouldn’t be more than what’s in a can of Coke,” Andrew Alvarez, an IBISWorld research analyst who specializes in the food and beverage industry, says. “So it could be devastating for the soda industry, which has already seen its share of devastation over the past 10 years.”

Advocates say these steps will help Americans make healthier choices and cut down on the nation’s rising obesity rates. Opponents point out that there is no difference between the way the body processes added and natural sugars, and say the FDA’s proposed label, shown below, will confuse consumers. General Mills told the FDA only 66 percent of consumers the company surveyed could correctly identify the total sugar content of products based on the new label compared to 92 percent for existing labels.

“There is concern among the food industry that just adding more information on the label will not allow consumers to make healthier choices,” Cary Frye, vice president of regulatory and scientific affairs at the International Dairy Foods Association, says.

Frye also says food companies will have to spend “hundreds of millions of dollars” to revise nutrition labels for every product. But Paul Bakus, president of corporate affairs at Nestlé, says companies update many nutrition labels every year or so anyway, so thinks the impact will be “fairly low cost.”

Regardless, the FDA seems determined to move forward, and food companies are questioning what exactly the agency’s proposals mean for their products. Will consumers heed the FDA’s suggestion to limit added sugars to 50 grams per day? Will they scrutinize nutrition labels at the grocery store? Will the labeling change impact sales of sugary products, or pass by without much notice?

Laura MacCleery, director of regulatory affairs at the nonprofit Center for Science in the Public Interest, believes labeling could be a “very powerful” driver for companies to reformulate their products -- particularly in products with alarmingly high levels of added sugars such as cereals, yogurts and sodas. “When the FDA added a labeling line for trans fat, 75 percent of the trans fat dropped out of the food supply over a period of years,” she says.

Alvarez, the analyst, is more skeptical: “We're talking about their greatest hits -- products that have a certain flavor and texture and taste that consumers have come to know,” he says. “The removal of added sugars could drastically change the product and that would perhaps be more devastating than losing some consumer goodwill.”

Some companies have already pursued sugar reductions in their products.

Nestle, which manufactures Toll House cookies, KitKats and Dreyer’s ice cream, pledged to reduce the sugar content in a select group of products by 10 percent in 2015. It published an official sugar policy and endorsed recommendation by the World Health Organization and FDA to limit consumption of added sugars to 10 percent of a person’s daily caloric intake (about 50 grams a day).

“Our approach to our business is to help consumers make good choices and be responsible with our products,” Bakus says.

Earlier this year, Nestle debuted new versions of Nesquik, a flavored milk product, with fewer added sugars. Since 2000, the company has reduced the added sugars in Nesquik chocolate powder by 35 percent to 10.6 grams per serving simply by adding more cocoa and other natural flavors. In a separate project, the company reduced the amount of sugar in sugar-filled straws called Pixy Stix by making the straws smaller in size. They now contain 10 grams of sugar instead of 26 grams. About half of the added sugars Americans consume come from beverages such as soda and fruit juice, while 6 percent come from candy.

For the moment, Frye of the International Dairy Foods Association says it’s too early to tell whether other companies will change their products in response to the FDA’s new proposals. Dairy producers have said the agency’s definition of “added sugars” isn’t clear enough, and are waiting for more details.

One major concern for the dairy industry is that sugar occurs naturally in milk as lactose. Manufacturers sometimes add a form of dried milk known as “milk solids” in dairy products to boost protein, but those protein-rich solids also contain lactose.

Bridget Christenson, spokeswoman for General Mills, says the company used this strategy to reduce the sugar in Yoplait Original yogurt by 25 percent. The new version was launched in March. “The addition of dairy allows us to maintain a smooth and creamy texture, while also delivering additional protein,” she says. But Frye says much of the industry is waiting for clarification on whether adding milk solids counts as adding sugars.

It will take time to determine whether more companies will reduce added sugars in their products. Bakus says companies typically make gradual changes over time rather than in one fell swoop, so as to avoid startling consumers with an unfamiliar taste.

He also says that after 29 years in the industry, he doesn’t expect the addition of added sugars to the nutrition label to dramatically impact sales or change consumers’ decisions: “Ideally, this is just another piece of data that consumers can use.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.