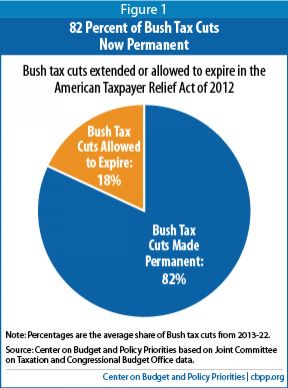

Fiscal Cliff Deal Preserved 82 Percent Of Bush Tax Cuts

The Bush tax cuts were the at the center of the recent fiscal cliff deal, with Democrats ultimately winning the fight to restore the top 39.6 percent tax rate on annual incomes above $400,000.

But despite that small victory for Democrats, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports that the budget deal isn’t exactly what it seems. In fact, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 actually made 82 percent of the George W. Bush-era tax cuts permanent, according to analysis from the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Congressional Budget Office, which found that the law made all but $624 billion of those $3.4 trillion in tax cuts permanent.

Only the wealthiest 0.7 percent of taxpayers are affected by the rise in individual tax rates and estate tax rates included in the recent deal. Still, after months of public debate over the merit of allowing the Bush tax rates to expire for all but the poor and middle class, it turns out only 18 percent of revenue lost from those cuts will be recovered. That 18 percent includes $453 billion over 10 years from the expiration of cuts to the income, capital gains and dividend tax rates on the wealthiest earners; $152 billion from placing limits on personal exemptions and itemized deductions on single incomes above $250,000; and $19 billion from raising the estate tax rate from 35 percent to 40 percent.

How The Budget Deal Benefits Top Earners

However, the new estate tax guidelines are generous -- too generous, according to CBPP founder and President Robert Greenstein. The budget deal exempts the first $5.2 million of an estate from taxation in 2013, which increases to $10.4 million for a couple. These new permanent rules expanded on parameters set in 2009 that made the first $3.5 million of an estate -- $7 million for a couple – fully exempt from the tax.

“What remains of an estate after this large exemption and various deductions will be taxed at a 40 percent rate,” Greenstein wrote in a statement, discussing the change. “The difference between these new permanent rules and the 2009 rules is a revenue loss of $118 billion over the next 10 years. Only the estates of the top 0.3 percent of people who die will benefit, and they will receive an average tax break of about $987,000 each.”

In contrast, several tax credits intended for low-income families -- such as the Child Tax Credit, the Earned Income Tax Credit and the American Opportunity Credit -- were only extended for five years until 2017, something Greenstein described as "appalling."

“Something is amiss when the Senate's minority leader insists that a million-dollar average tax break for the heirs and heiresses of the richest three of every 1,000 people who die must become the permanent law of the land, while tax measures that lift millions of children in working-poor families above or closer to the poverty line must die,” Greenstein wrote.

The U.S. Census Bureau reports the tax credits in question helped lift an estimated 1.5 million Americans out of poverty in 2011, in addition to lessening the severity of poverty for another 15.2 million people, including 7.1 million children.

What About The Remaining 82 Percent?

Democrats aren’t done pushing for new revenue. While Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell on Sunday told ABC News that “the tax issue is behind us,” Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois had something different to say during an interview with CNN’S Candy Crowley. Durbin, in response to a question about whether tax rates have been raised “enough” on the wealthy, discussed the need for broader tax reform to close off additional deductions, credits and loopholes that almost solely benefit high-income earners.

“We forgo about $1.2 trillion a year in the tax code, money that otherwise would go to the government, and when you look closely, some of those things are near and dear to us individually and to the economy -- the mortgage interest deduction, charitable deductions, deductions for state and local taxes, but beyond that, trust me, there are plenty of things within that tax code, these loopholes where people can park their money in some island offshore and not pay taxes, these are things that need to be closed. We can do that and use the money to reduce the deficit,” Durbin said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.