Is Football Safe? New 'Concussion' Movie Stirs Debate Over Risks For Young Athletes

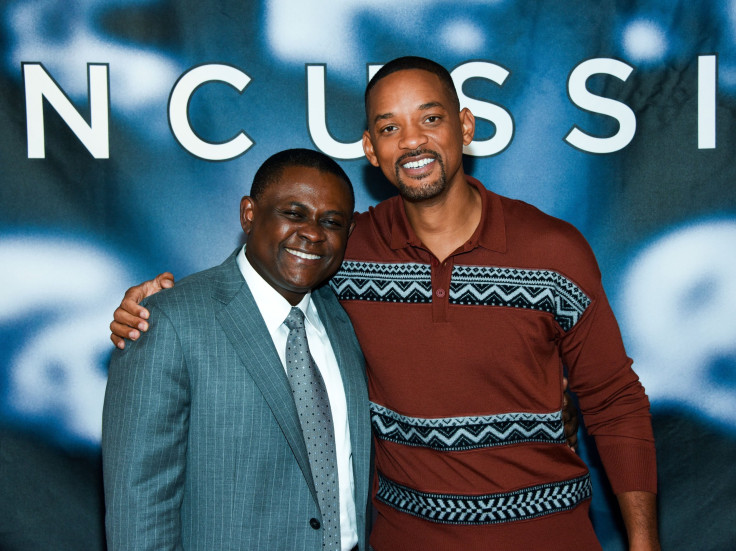

Just weeks before the Super Bowl, a film starring Will Smith is tackling one of the most troubling issues in American sports today. Smith’s leading role in "Concussion," which opened Friday, follows the career of Dr. Bennet Omalu, a pathologist who was the first to diagnose a debilitating disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy in the brain of a former NFL player when he posthumously examined retired Pittsburgh Steelers linebacker Mike Webster in 2002.

As the film describes, Omalu’s discovery was a grave warning that football can inflict long-term brain damage on pro players. Since then, Omalu has extrapolated his findings on CTE in professional athletes to conclude that football is not safe for children. But many of the same experts who credit him with galvanizing concussion research do not agree that youth and high school football should be banned.

“I think he's a bright guy, but he's often a loose cannon and has opinions that aren't based on practicality or science,” said Dr. Robert Cantu, a neurosurgeon and co-director of Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy.

Omalu, now the chief medical examiner for San Joaquin County, California, penned a Dec. 7 New York Times editorial titled “Don’t Let Kids Play Football.” He argued that no one should play the game before the brain is fully developed, between the ages of 18 to 25. He said “repetitive blows to the head” such as those sustained in football put athletes at “risk of permanent brain damage" and drew analogies between the dangers of football and the cancer-causing properties of smoking and asbestos.

Many of Omalu's peers, however, say that prescription and his analogies are a bit too strong. “I think some people say, here's the person who first discovered CTE and they must be very authoritative and we should err on the side of caution,” said Dr. Ken Adams, a neuropsychologist at University of Michigan. “But the science underlying the precise sweeping prescriptions like that just isn’t there.”

Many experts have pushed for changes to make football safer for kids. Others have called for postponing tackle football until middle school. In October, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a position statement recommending instead that coaches teach safe tackling techniques rather than limit tackle football to a certain age. The American Academy of Neurology recommends regulations that minimize the risk of concussions but does not call for a ban. Omalu’s proposal went much further than any other.

“Despite my respect and admiration for all he has done, I respectfully disagree with his stance that kids should not play contact sports, including football,” said Dr. Julian Bailes, a neurosurgeon who is co-director at NorthShore Neurological Institute in Chicago and medical director for Pop Warner, the nation’s largest youth football league. Bailes encouraged Omalu to pursue his work despite the NFL’s opposition, and his role is featured prominently in "Concussion." A representative for Omalu said he was not available to comment over the holidays.

Meanwhile, parents are left wondering what this all means for the 4.8 million middle and high schoolers who play football today. Already, their enthusiasm for the hard-hitting sport seems to have faltered despite new rules that limit the number of full-contact practices in a season and rules that prohibit concussed players from going back into the game. Pop Warner saw a 9.5 percent dip in registration from 2010 to 2012, which Bailes said was partly due to parents’ concerns about concussions.

Dr. Lynn Schaefer, director of neuropsychology at Nassau University Medical Center in Long Island, New York, said "Concussion" could further stoke these fears. “Much of the media that's coming out of sports concussions and CTE has been dramatized, and it's really the story that's driving everyone's fear rather than the science,” she said. “We don't hear about the tens of thousands of other professional football players that went on and were fine.”

Since researchers have only recently begun to study the link between football and mild traumatic brain injuries including concussions, they remain unable to answer questions that would give parents and young players a clearer picture of the game’s risk. Those questions include: What is the chance that any given youth football player will develop long-term brain damage? Could a single concussion cause CTE? Are repeated sub-concussive blows to the head endured by football players likely to result in permanent brain damage? Why do some people develop CTE and others do not?

Critics point out that had the NFL been more proactive about the problem, researchers might already have had answers to some of these questions. The NFL at first refused to acknowledge Omalu’s findings and sought to discredit him publicly. Earlier this year, the league settled a $1 billion lawsuit to cover any long-term health costs related to neurological damage for thousands of former players.

Still, most experts agree that athletes fully recover from a majority of concussions and the sport plays an important role in many children's development. Young athletes who suffer multiple concussions do seem to have diminished long-term cognitive health. But until the total risks are better understood, Omalu’s prescription seems excessive to many.

“Probably the human body was designed to handle a few bumps and concussions, because I think we wouldn't be here as a species if we weren't able to manage that at some level,” said Dr. Christina Master, a sports medicine pediatrician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “The question is — where is that cutoff point?”

Bailes says there never has been a documented case of a child developing CTE from youth sports. Dr. Andy Gilliland, a sports medicine physician in Kentucky, treats about 100 concussed athletes every fall as a team physician at three nearby universities. “The perception that all concussions are devastating I think is an unfair perception,” he said.

Cantu at Boston University has called for a ban on tackle football before the age of 14. While he agrees with Omalu that it would be safer to wait until players’ brains are fully developed, he sees this as an impractical suggestion. He points to a study published this year in the journal Neurology of retired NFL players that shows those who started to play before the age of 12 had greater cognitive impairment than those who started later. He says by 14, adolescents’ brains have developed most of the myelin, a protective sheath that coats neurons, that they will have as adults.

Dr. Lewis Margolis, a pediatrician at University of North Carolina, agrees with Omalu, but his argument against football is a precautionary one until the evidence is clearer. He published an article in the July-August issue of the North Carolina Medical Journal arguing that permitting patients to play football in high school violates the physician’s “do no harm” obligation.

“I say, enough is enough,” he said. “There's a risk here and it's not a trivial risk so that we should step back and say, ‘Wait. we need to look at this more closely.’”

Dr. Larry Rogers, a retired neurosurgeon at Carolinas Medical Center, quickly fired back with a retort that eliminating the sport entirely would be “tossing the baby out with the bathwater.” Master in Philadelphia fears that eliminating football altogether will limit kids’ opportunities to stay active and develop skills such as teamwork.

“I am all for this conversation and awareness, but I want to make sure we don't have that pendulum swing the other way where we have families that decide, we're not going to play sports because it's too dangerous,” she says.

If Omalu’s suspicion about the long-term dangers of youth football are correct, mustering the political and social will to ban or significantly change the game could prove an even greater challenge than publicizing early evidence of CTE.

“It doesn't seem to me that America’s going to say, we've got to shut down the NFL,” Adams, the neuropsychologist at University of Michigan, says. “That's not going to happen.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.