Gene Variant That Boosts UV Protection Also Raises Risk For Cancer

A gene variant common among caucasians offers more protection from the harmful effects of UV radiation, but also leaves a person more likely to contract testicular cancer.

"The genetic risk factor we identified is associated with one of the largest risks ever reported for cancer," author Douglas Bell, a researcher at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institutes of Health, said in a statement. (Bell is currently on furlough thanks to the federal government shutdown and could not discuss his research in an interview.)

Bell and his colleagues reported their find in the journal Cell on Thursday.

"We think it might prove useful for identifying individuals at the highest risk for cancer or who might benefit from preventive or therapeutic treatments,” Bell says.

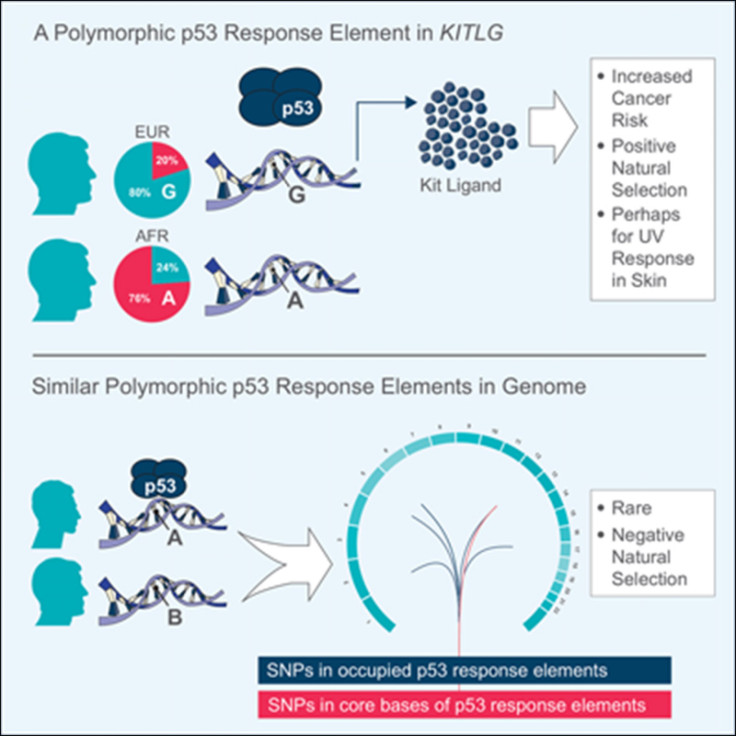

The gene in question is a binding site made for a protein called p53, which is an important genetic master switch, binding to DNA and regulating the cell division cycle and suppressing tumors – when it works properly, that is. Mutations in p53 are implicated in a wide range of cancers, so Bell and his colleagues were interested in examining mutations in other parts of the p53 signaling chain.

Bell and his team were led to this particular mutation by what are called “genome-wide association studies.” In these kinds of studies, scientists compare the genomes of people with a certain trait, like cancer, to the genomes of people without the trait. If they see that a certain gene tends to crop up more often amongst the people with the trait, they may says the gene is associated with that trait.

In this study, the researchers zoomed in on a p53-binding region in a gene called KITLG. When UV radiation hits a person’s skin, it induces a signaling chain involving both the KITLG gene and p53, eventually marshaling the melanin-producing cells that trigger a tanning response. KITLG activation by p53 also turns out to be important for cancer-related cell proliferation.

Normally, evolution might be expected to weed out the p53 binding site mutation, but in this case, in lighter-skinned people the protection from UV radiation proved more urgent a need than cutting cancer risk down the line. It’s not uncommon in nature to see some trade-offs that boosts short-term survival or reproductive ability in exchange for reduced fitness down the line.

"It seems that over the long course of human evolution, the trade-off might have worked well enough to boost the frequency of the [mutation], especially in the European Caucasian population," coauthor and University of Oxford researcher Gareth Bond said in a statement. "I'd speculate that serious sun damage to skin would have posed a mortal threat to our early ancestors."

SOURCE: Zeron-Medina et al. “A Polymorphic p53 Response Element in KIT Ligand Influences Cancer Risk and Has Undergone Natural Selection.” Cell 155: 410 – 422, 10 October 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.