George Orwell '1984': Interest In Dystopian Novel Surges In Wake Of Trump Administration's 'Newspeak'

George Orwell’s “1984” has been enjoying a rebirth since the inauguration of President Donald Trump and senior adviser Kellyanne Conway’s use of the term “alternative facts.”

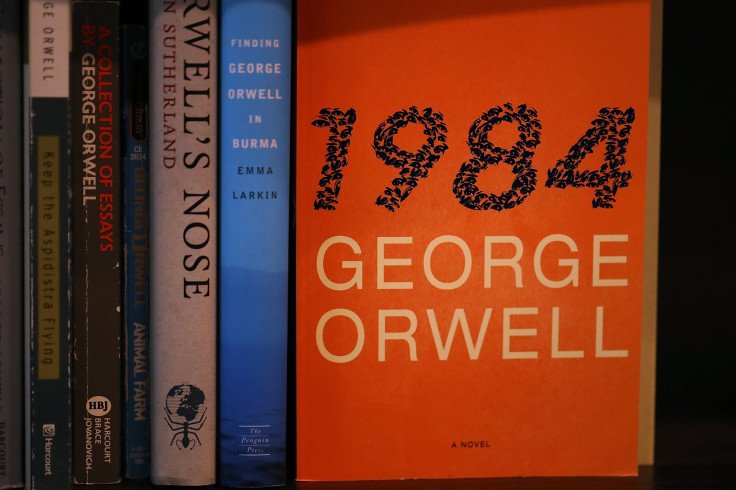

The 1949 novel is a dystopian view of British society when it’s taken over by a totalitarian regime that uses “doublethink” and “newspeak” — yes means no and no means yes — to control the population.

Conway, complaining on Jan. 22 about how Trump has been treated by the press, denied on NBC’s “Meet the Press” that the administration was offering falsehoods when press secretary Sean Spicer insisted more people had witnessed the Trump inauguration than any other inauguration in history. Instead, she said, the administration was offering “alternative facts.”

The San Francisco Chronicle reported Friday a “mysterious benefactor” bought 59 copies of the novel at Booksmith in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood to be given away for free. Store owner Christin Evans said the books were placed on a table, accompanied by a sign reading, “Read up! Fight back!” The copies disappeared within a few hours.

Then someone bought copies of Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” — about a theocratic U.S. regime that strips women of their civil rights — and Erik Larson’s “In the Garden of Beasts” — about an American family living in Hitler’s Berlin.

The Los Angeles Times reported Monday “1984” was No. 3 on Amazon’s best-seller list. It had claimed the No. 1 spot on the Wednesday after Conway’s remarks.

Penguin announced it was ordering a 75,000-copy run of the novel. Penguin publicity director Craig Burke told the New York Times sales increased 9,500 percent after Conway’s remarks. Interest in the novel also has increased in Britain and Australia.

“Everyone remembers ‘1984’ as containing various parodies of official distortions,” Stefan Collini, a professor of intellectual history and an expert on Orwell at the University of Cambridge, told the New York Times.

“That kind of unreality that is propagated as reality is what people feel reminded of, and that’s why they keep coming back.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.