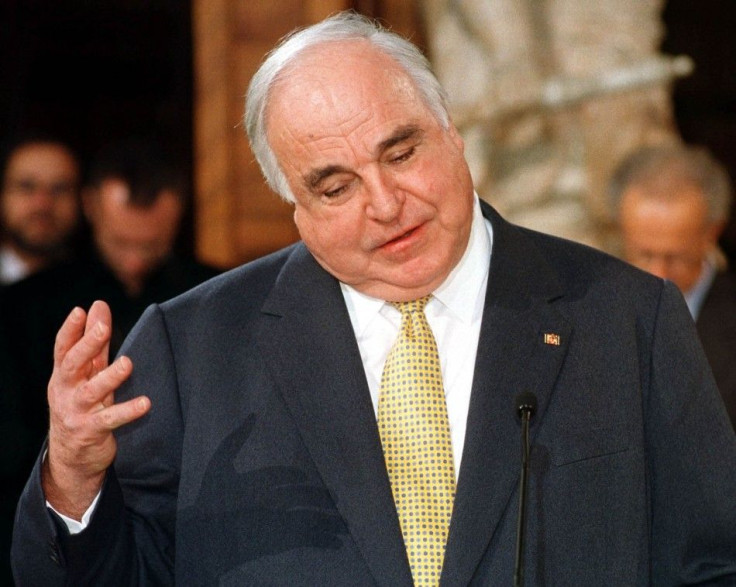

Get Back! Former Chancellor Helmut Kohl Once Planned To Expel One-Half Of Germany’s Turkish Immigrants

Former West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl wanted to send one-half of the country’s Turkish immigrant population back home, according to secret British documents from the National Archives. Spiegel Online reported that in 1982 the newly elected Kohl told British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of his plan to reduce the number of Turks in West Germany by 50 percent over the next four years during the latter’s visit to Bonn, then the capital of the country.

Minutes from the secret report, which have now been made public after the period of confidentiality has expired, stated that "Kohl… could not say this publicly yet… [But he felt] it was impossible for Germany to assimilate the Turks in their present numbers." Interestingly, according to the document, Kohl only targeted the Turks for expulsion, saying that Germany “had no problems with the Portuguese, the Italians, even the Southeast Asians, because these communities integrated well.” But Turks formed, by far, the largest foreign population in the country, having been invited as “gastarbeiter” (guest-workers) in the 1960s.

The report noted that Kohl felt that Turks “came from a very distinctive culture and did not integrate well.” He cited that too many Turks engaged in practices like forced marriage and worked illegally. Of the Turks he would allow to remain in Germany, they would be provided with special schooling and encouraged to assimilate with German society. The only other people in the room when Kohl informed Thatcher of his grand plans were Kohl’s adviser Horst Teltschik and Thatcher’s private secretary A.J. Coles, who wrote the document in question.

Indeed, two weeks prior to his meeting with Thatcher, Kohl declared in a policy speech that: "integration is only possible if the number of foreigners living among us does not increase further." Spiegel suggested that if Kohl’s plan ever came to fruition, it would have enjoyed widespread support among the German populace. "Back then, the societal consensus in Germany was that Turks were guest workers and would have to go home," Ulrich Herberta, a German author and historian, told Spiegel.

In response to Spiegel’s revelations, Kohl’s office conceded the report was correct. “At the time, [Kohl's plan] … was part of a broader debate on immigration policy," stated his Berlin office on Friday, but added that the former chancellor “is not prepared to make any further comment on the issue.”

In 1982, at the time of Kohl’s mini-summit with Thatcher, some 1.5 million Turks were settled in Germany, including the wives and children or the original male guest workers. (At that time, some 1.8 million Germans were jobless.) "The politicians in Bonn were overwhelmed," added Herbert. "They were afraid of being overrun with Turks, and wanted to get rid of them. But they didn't know how."

Kohl’s plan was to provide financial compensation to Turks to return to their native land. And, in fact, in 1984, the German state passed a law that would just do that -- a one-time payment of 10,500 deutschemarks for Turks to repatriate. "Only about 100,000 Turks left," said Herbert.

Kohl, who is now 83 years old, had a dramatic change of heart with respect to foreigners by the early 1990s, after a wave of xenophobic attacks shocked Germans. In 1993, Kohl supported a measure to grant automatic German citizenship to the German-born third-generation of immigrants, in defiance of his own party, the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU). He even praised immigrants for having contributed "enormously to the well-being of Germany.” In 2000, Kohl went to Istanbul to attend the wedding of his son Peter to a Turkish banker. Kohl ruled Germany as Chancellor for 16 years, with his final term expiring in 1998.

Now, some 3 million Turks live in Germany, with many having assumed German citizenship. They represent a little less than half of the country’s total “foreign” population. Still, many Turks remain far outside of Germany’s mainstream, while a labor shortage in the country encourages the arrival of more skilled workers. Kenan Kolat, chairman of the country's Turkish Community Organization, said of Kohl’s program that “today's political class would never get away with that sort of thing. That's progress," according to the Berliner Zeuting newspaper.

But Memet Kilic, an MP for the Green Party, commented: "Whilst the exposure of Helmut Kohl's way of thinking may be a novelty, it is a mindset that has been espoused by the … CDU and its Bavarian sister party for decades."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.