Global Warming Effects: Great Barrier Reef In Grave Danger, But Not Dead Yet

An obituary for the Great Barrier Reef published Tuesday on the website Outside Online can best be described as colorful and effective hyperbole, but the world’s largest living structure is certainly in serious trouble.

"Obituary: Great Barrier Reef (25 Million BC-2016)," by Rowan Jacobsen went viral by proclaiming that the world's largest coral reef system was deceased. "The Great Barrier Reef of Australia passed away in 2016 after a long illness," reads the fake obit. "It was 25 million years old."

The Great Barrier Reef of Australia passed away in 2016 after a long illness. It was 25 million years old: https://t.co/TrEXJuTxFJ #RIP pic.twitter.com/7U3wPDPSM2

— Outside (@outsidemagazine) October 12, 2016

Social media and scientists were quick to point out the sensational article. Even Finding Nemo’s Dory had something to say:

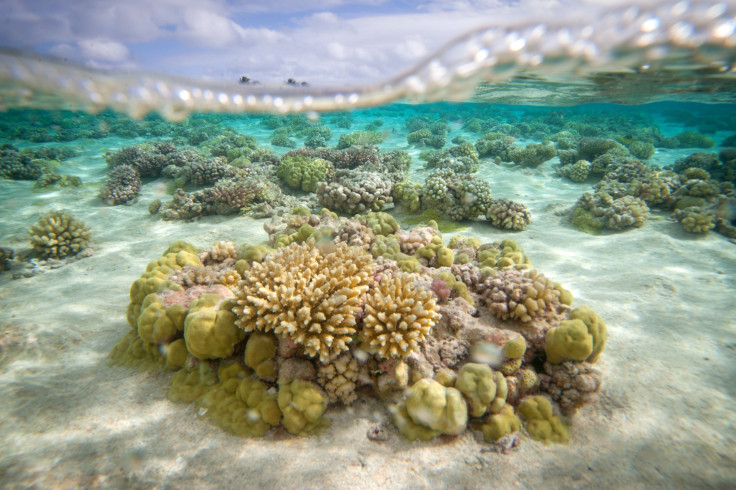

The Great Barrier Reef, which stretches for over 1,400 miles off the coast of Australia, has been severely affected by rising water temperatures, which is due to global warming. The rising sea temperatures are directly linked to coral bleaching, which can have very damaging effects.

Stephanie Wear, The Nature Conservancy’s director of coral reef conservation, provided a thorough explanation of coral bleaching.

"The first thing to understand is that corals get their brilliant colors from tiny algae that live in their tissues. These tiny organisms live in harmony with coral animals, and they basically share resources.

"For example, the most important thing that the algae do is provide food to the corals through carbohydrates they produce during photosynthesis."

"The next thing to understand is that corals have a limited temperature range within which they can live.

"When it gets too hot, they get stressed out—and this relationship with the algae goes sour. The tiny algae are ejected from the corals, turning them white, thus the term 'bleached.'

"If these algae aren’t reabsorbed in the near term, the coral will die. They just can’t survive long-term without them."

Of more than 900 reefs surveyed earlier this year, 93 percent were found to have been affected by coral bleaching, according to a report conducted by the Arc Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released a report this summer on coral bleaching. "It’s time to shift this conversation to what can be done to conserve these amazing organisms in the face of this unprecedented global bleaching event,” said Jennifer Koss, NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program director in the report.

Coral reef damage isn’t just limited to Australia. Indian Ocean islands like the Maldives have already experienced massive coral bleaching, and researchers think the Northern Hemisphere could be next: Hawaii, Guam, the Florida Keys, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico are all likely to be hit hard by coral bleaching.

But is the Great Barrier Reef on its death bed, as Jacobsen suggests?

“For those of us in the business of studying and understanding what coral resilience means, the article very much misses the mark,” Kim Cobb, a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s not too late for the Great Barrier Reef, and people who think that have a really profound misconception about what we know and don’t know about coral resilience.”

Conservations still have hope. An airborne mission by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is investigating Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.