Going It Alone: The Frightening Costs Of Retirement Security In The 401(k) Age

On the road to retirement land, Americans aren’t putting enough gas in the tank. New research from leading retirement security experts shows that shortfalls in 401(k) accounts -- the dominant savings vehicle in the private sector -- are large, and that the cost of filling them is much greater than people realize.

The bottom line: Americans are not accumulating nearly enough money in these accounts to provide a comfortable retirement.

As Alicia Munnell, co-author of the new book "Falling Short: The Coming Retirement Crisis and What to Do About It," wrote in MarketWatch this week, 401(k) plans just aren’t working well.

“The typical household nearing retirement with a 401(k) holds only $111,000, including any assets that were rolled over into IRAs,” she writes. Meanwhile, half of the private sector workforce isn’t enrolled in an employer-sponsored plan at work. “If things continue as they are,” Munnell writes, “more than half of today’s working households will not be able to maintain their standard of living once they stop working.”

In contrast to pensions, in which a group's assets are pooled together and professionally managed, a 401(k) is a sole account, and the employee, by and large, chooses what to invest in. Among private sector workers with a retirement plan, the percentage who had only a pension fell from 62 percent in 1979, to 7 percent in 2011, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute. Conversely, during the same period, the percentage who participated only in a 401(k)-type plan rose from 16 percent to 69 percent.

The decades-long shift from pensions to 401(k)s has suited a mobile workforce that can carry this type of plan around from job to job, as opposed to leaving a pension parked with a previous company. But it has also suited employers, who have been able to hoist all the risk for meeting retirement needs off their books and onto yours. Generally, in a pension (also known as a defined benefit, or DB, plan), your employer guarantees you a certain benefit when you retire, to be paid until you die. With a 401(k) (or defined contribution, or DC, plan), you are guaranteed only as much money as you have managed to invest, plus the return that investment has generated.

Pensions: The Lost Advantage

This shift has sacrificed a key virtue of pensions: their efficiency. Pensions can earn more with a dollar than a 401(k) because they can draw on economies of scale (everyone’s assets pooled together) and professional asset management, according to new research from the National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS). In other words: Pick the amount you want to receive during retirement, and pensions will deliver it at a far lower cost than a 401(k) could.

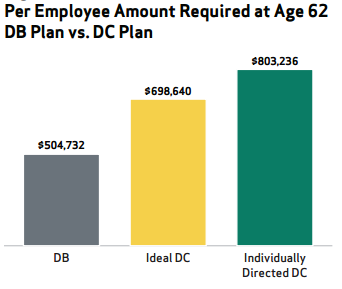

According to the analysis, a typical large public pension generates a 48 percent cost saving when compared with the typical individually directed 401(k). Even compared with an "ideal" 401(k) plan in which individuals make stellar investment decisions, the pension plan produces a 29 percent cost advantage.

The NIRS analysis underscores how much heavy lifting 401(k)-enrolled employees have to undertake, compared with pension-enrolled employees. The study constructs a model group of 1,000 female teachers. They start working at age 30. They retire at age 62, with a break along the way for child-rearing. They’re aiming for an annual retirement benefit of $32,036 -- 53 percent of their final year’s wage -- that, when combined with Social Security, “will allow our 1,000 teachers to achieve generally accepted standards of retirement adequacy,” the paper explains.

The authors then calculate three different savings trajectories to reach that goal. One retirement plan is a public pension (which is regulated differently from a private sector pension). The second is the “ideal” 401(k) and the third is a 401(k) in which employees make more typical investments (i.e., not as good as those in the “ideal” version).

How much has to be set aside in each type of retirement account to reach the goal? The difference between the pension plan and the two 401(k) plans ranges from about $200,000 to $300,000 more. Take a look at this chart:

How To Boost Savings

So what does this mean in the short term for workers and in the long term for the U.S. retirement system?

For one thing, employees aren’t going to reach an adequate retirement income by relying on the typical 3 percent-of-pay contribution that employers kick into 401(k)s. “Most people don’t understand how much it really takes to get to that level,” says Diane Oakley, executive director for NIRS. More likely an employee “probably has to put away 15 percent of pay from the time they are in their 20s until age 67,” she adds.

Retirement experts also worry about “leakage” from 401(k)s. When young workers switch jobs, they may be tempted to empty accounts that contain only a few thousand dollars. But spending that money is a big mistake. “In a defined contribution model, those first dollars you put in ultimately become very powerful, because compound interest works on those dollars for 40 or 45 years,” Oakley says.

Employees who change jobs, or careers, in their 40s or 50s may also want to consider taking a job that offers a pension. “That could be a great way of making up for the lack of savings they had early in their career,” she says.

Oakley herself made that kind of move, at age 50. She gave up more than half her private sector salary to work for a member of Congress for six years. In return, she’ll get pension payments starting at age 62 of about $800 a month -- enough to pay her mortgage -- for as long as she lives.

Indeed, the NIRS paper argues that more workers should have access to this kind of guaranteed income stream and that policymakers should focus on strengthening existing pensions and promoting the creation of new ones.

People should have a choice, Oakley says: “What the private sector has done is they’ve just given up on this DB model in many ways, even though they know it’s probably more cost-effective.”

Given the prevalence of 401(k)s, however, Jean-Pierre Aubry, a colleague of Alicia Munnell’s at Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research, is more skeptical of this approach. “I don’t think there’s an appetite out there in terms of employers wanting to go back into the [defined benefits] game,” Aubry, the center’s director for state and local research, tells International Business Times.

Rather, he says, “the other way forward is to shore up the 401(k) apparatus.” That would entail fixes like auto-enrollment, to get more workers in the system in the first place; auto-escalation to increase contribution rates; and efforts to cut down on 401(k) leakages. “It shouldn’t be used as a savings account that you can access whenever you want,” he says.

States are starting to experiment with a variety of ideas on this front. This month, for example, the Illinois legislature approved a bill to create a retirement savings plan for private sector workers who don’t have access to one. If Gov. Pat Quinn signs the bills into law, employers with 25 workers or more would have to offer the retirement vehicle.

Following the financial crisis, states including Georgia, Michigan and Utah, among others, have been creating mandatory pension-401(k) “hybrids” for public sector workers. Hybrids are attractive to states, Aubry explains, because they “lower the DB promise” and share more of the risk with employees through the 401(k).

Ultimately, though, Oakley insists that retirement security has to become the subject of broader focus in the U.S.: "We really haven’t had a policy discussion nationally to say, will people have enough to maintain their standard of living?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.