Holocaust Memorial Day: Apples Kept Paula Kreiter Alive In Auschwitz, Notorious Nazi Death Camp

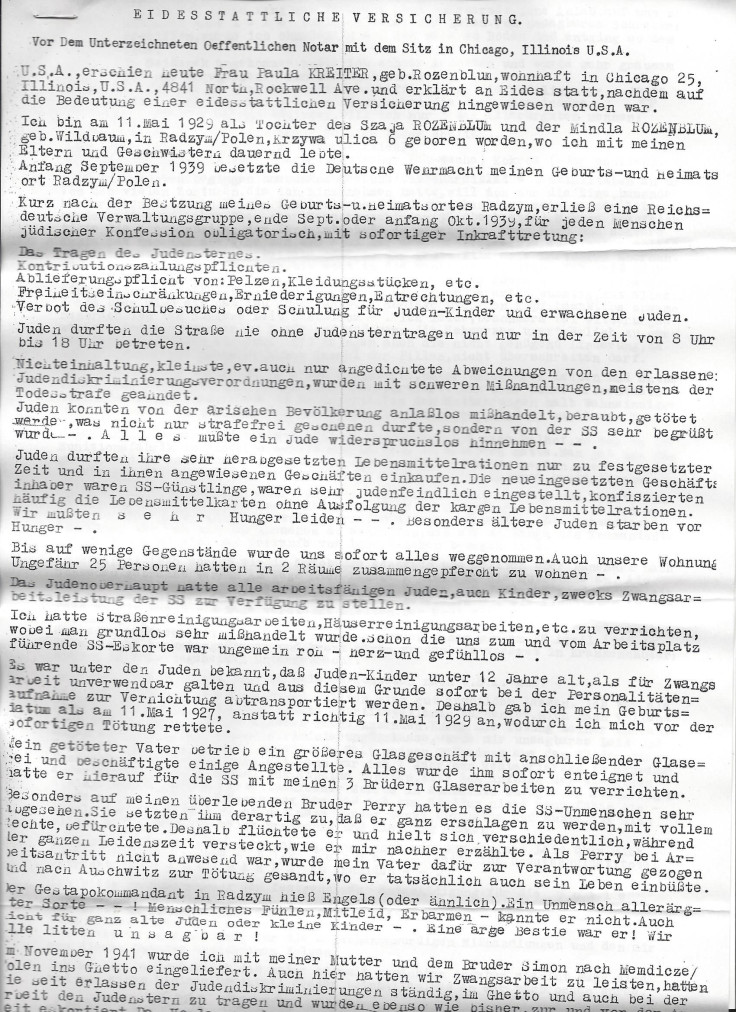

My mother, Paula, was just 11 when the first German bombs of World War II fell on the Polish town she called home, Radzyń, about halfway between Warsaw and what was then the Russian border. The town, which probably had about 10,000 residents at the time, isn't in the same spot anymore. It moved after the war that wiped out nearly her entire family. She had seven brothers and sisters, nearly a dozen aunts and uncles, and the many cousins that go with those numbers.

That first day, the mayor urged everyone to go to the park. He said they'd be safer there. My mother was sitting between her two sisters. They were both hit by shrapnel and died instantly. Mom has never figured out why she was spared, and her mother never looked at her the same way after that.

It was a short time later when her oldest brother, Perry, a communist who had spent a year in jail for his beliefs, fled to Russia, leaving behind a wife and child who would eventually make their way back to Radzyń from Warsaw to be with family.

When the Nazis marched in, my grandfather was arrested in lieu of the communist son who had fled. My mother never saw him again. When her brother tried to come back for his wife and child, the Russians sent him to Siberia for the remainder of the war, accusing him of spying. He was the only other member of the family to survive the war.

Since mom was fluent in both Polish and Yiddish, she became the go-between for the German soldiers (Yiddish was close enough to German for her to be able to pick up the new language quickly). She would trade chocolate for eggs and other staples available from the surrounding farms. Her second-oldest brother, Izak, was put to work as a glazier, the family business.

In November 1941, the family was herded into one of the ghettos, Memdicze. Izak was left behind. The remaining family shared quarters with dozens of other people. The Nazis tried to kill off as many ghetto residents as possible, poisoning the well water with typhus. My mother survived.

Then in May 1943, the Nazis decided to clear the ghetto. The residents were put in two lines, one destined for Treblinka, the other for Maidenek. Mom was in the Treblinka line with her mother but wanted to be with her brother, Simon. The two were less than a year apart in age. So when the guards weren't looking, she dashed across to the other line. That was the last time she saw her mother.

The following August, the Nazis had the Jews line up again. This time it was for a trip to Auschwitz. People died standing up in the box cars. At Auschwitz, again, the group was divided into two lines, one going directly to the gas chambers. Simon was in that line. My mother was sent to the work camp side.

For 18 months she picked apples and collected reeds for baskets. Those apples likely saved her life. The pickers would fill their dresses with apples to take back to their barracks to augment the meager rations they were given. My mother said the soup was made from poison ivy. She refused to eat it. The bread usually had mold. She ate it anyway, traded apples for it.

In December 1944, she was shipped to Ravenbruck and the next month to Malhof, where she worked in a munitions factory, filling bullets with gunpowder -- until the machine exploded and the Germans no longer had a way to fix it.

On April 17, 1945, the Swedish Red Cross arrived. The trip out of Germany was hazardous. Bombs were still falling, but the bus made it to Denmark in three days, and from there the refugees were transported to Upsala, Sweden, where they were housed at the university, fed, clothed and allowed to recover. She became fluent in Swedish and started learning English.

It took a year of searching for my mother to find her uncle in Chicago, where he had fled during World War I, ran a glass business and raised a family. One of his sons was just a year younger than mom. She arrived at the end of April, the first Holocaust survivor to do so, following a trip on a luxury liner.

It took several more years for her to find her surviving brother, Perry. By that time he was remarried with a newborn son. She signed the papers and brought him to the United States as well. When he finally arrived in Chicago, he had a second son, my age.

The memories of the war never faded, even though her uncle made her throw out the diaries she had kept. "You're in America now. Forget it," he would tell her. Still, there were nights she'd wake up screaming. Thunderstorms sent her hiding in a closet as she recalled the bombs falling.

But she survives. And she never forgets.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.