How ISIS Pillages, Traffics And Sells Ancient Artifacts On Global Black Market

Days before the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria took control of the major city of Mosul, Iraqi officials seized more than 100 computer flash drives with detailed information about the group’s activities. When they saw that ISIS had taken $36 million from an area called al-Nabuk, in Syria, authorities had a pretty good idea how it happened.

“The antiquities there are up to 8,000 years old,” an intelligence official told The Guardian this week.

Modern-day Iraq and neighboring Syria lie on top of what was once known as Mesopotamia or the Fertile Crescent, home to many of the world’s earliest cultures. Today it’s the resting place for things they left behind, and amid conflict, enterprising insurgents are taking advantage.

ISIS is now the richest terror group in the world. But beyond its cash recently acquired by robbing banks, the extremist group, like many others in the history-rich region, is entrenched in a billion-dollar black market for ancient artifacts.

“There is now secure (if imprecise) evidence that, like other parties to the Syrian civil war, [ISIS] is using the looting and trafficking of antiquities to fund its fighting,” wrote Sam Hardy, research associate at the UCL Institute of Archaeology in London, in a recent blog post.

"Conflict antiquities" are artifacts that are looted, smuggled and sold to illicit dealers around the world, with the proceeds going to fund military or paramilitary activity. Unesco estimates that globally trade in conflict antiquities could be worth more than $2.2 billion and growing as criminal groups recognize the value in very, very old things.

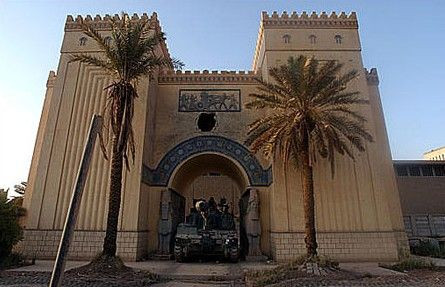

Though ISIS is currently taking advantage, looting in the region isn’t new, and escalated dramatically after the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003.

“Unlike Afghanistan, Iraq has no opium but it does have antiquities,” wrote Matthew Bogdanos, a colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps, who led an investigation into the looting of Iraq’s national museum while serving there in 2003, in a op-ed in 2011.

He said that while he was deployed there in 2005 every weapons shipment his unit seized also contained antiquities. In the caves, trucks and other hiding places, soldiers found “boxes of rocket propelled grenades alongside boxes containing ancient tablets and figurines.”

Criminal and terrorist groups are involved at various levels. Sometimes they run their own looting teams and follow the process from start to finish, but this is atypical. Generally, the members don’t do the dirty work themselves, but enlist locals.

“The majority of looters are subsistence diggers,” wrote archaeologist Peter Campbell, in a report last year, adding that they’re simply trying to make the best of a conflict situation to make some extra money. Typically, looters get less than 1 or 2 percent of the product’s market value, while middlemen like dealers, auction houses and others make most of the money.

From there, they move through various channels out of the country, with pretty modern tactics.

“The Internet has become a major conduit for criminal activities, so it is hardly surprising that illicit antiquities are available online,” Campbell wrote.

Smuggled Iraqi antiquities have been found as away as France, Italy and Switzerland, as well as closer neighbors such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iran and Turkey. In 2010 the FBI seized a handful of smuggled Iraqi cuneiform tablets from an antiquities dealer in California.

Trafficked items go to rich private collectors in the end. While it’s unlikely they show up in museums right away, collectors tend to wait a few years for suspicion to die down before donating or selling their finds to museums.

One way to combat the practice is for governments to start keeping tabs on the global black market, according to cultural heritage lawyer Rick St. Hilare.

“Such laws would foster transparency, helping to separate the legal cultural property trade from the illegal trade and serving to identify potential [money laundering and terrorist financing] crimes,” he wrote in a blog post.

The Financial Action Task Force, an independent organization that helps understand terrorist financing and money laundering, noted in its 2013 guidance report that trafficking in cultural goods and antiquities was one of many sources of money for terrorist groups.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.