How Zika Virus-Carrying Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes Were Eradicated, And Then Returned

Fred Soper was shocked. The year was 1967, and decades of painstaking work to eradicate the Aedes aegypti mosquito were unraveling before him. The pest was spreading once again, all over Central and South America, putting residents at risk of yellow fever, hemorrhagic fever and other deadly diseases. As the director emeritus of the Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Soper penned his concerns in a letter to the Brazilian Minister of Health, Dr. Leonel Tavares Miranda de Albuquerque, calling for the creation of a new agency to see to completion the eradication of the mosquito.

Soper’s efforts were ultimately futile. Nearly 50 years after the near elimination of the mosquito, broad swathes of the southern U.S. and much of South America and the Caribbean remain home to thriving populations of Aedes aegypti, a species that has attracted renewed attention with the outbreak of another virus, Zika, which it transmits. What happened over the course of that half-century, experts said, lays bare the challenges of eradicating a vector like the mosquito and serves as a subtle lesson for public health officials, governments and international agencies attempting to control an especially hardy breed of mosquito.

“Once they took the foot off the accelerator of sanitation reform, Aedes aegypti came right back,” said Joseph M. Conlon, a retired U.S. Navy entomologist who is now the spokesman for the American Mosquito Control Association. After the mosquito was eradicated, the reaction was, “Hey, why do we need to be spending all this money making sure people are discarding water from containers?” he said.

Sanitation reform, which for the purposes of controlling Aedes aegypti means getting rid of standing or stagnant water, where the mosquito lays its eggs, is the most effective way to eradicate Aedes aegypti, public health and mosquito control experts said. The World Health Organization has labeled mosquito control as the “best immediate line of defense” against Zika, in the absence of a vaccine for the virus.

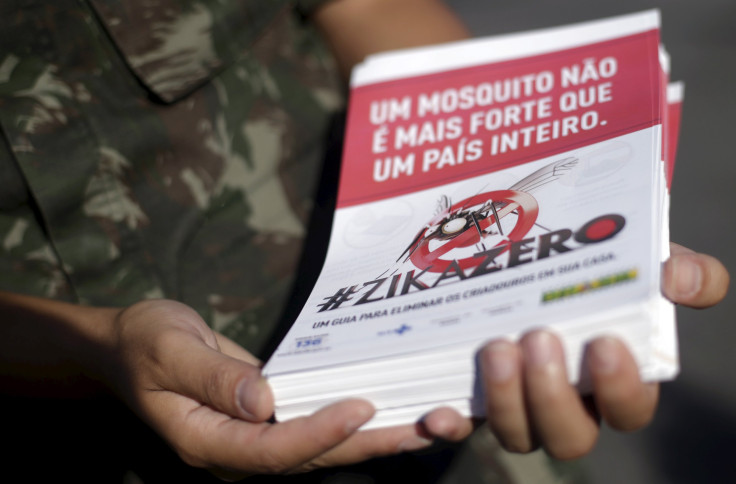

“It’s a pretty substantial process,” Conlon said. “Any mosquito control program involving Aedes aegypti has to involve public education,” where people are urged, through campaigns that involve public messaging, like distributing leaflets, to dump water that can collect in any number of seemingly innocuous household spots, from flowerpots to tires. “It’s not something people can be passive about,” he said.

And while these steps kill mosquitoes in their earlier stages of life, they don’t target adults, which is where fumigation using insecticides comes in, until young generations of mosquitoes can be fully wiped out. Still, Conlon said, “The real way to get rid of Aedes aegypti is through sanitation.”

Efforts to exterminate the Aedes aegypti mosquito began in the first half of the 20th century, after bacteriologist Walter Reed showed that the mosquito transmitted yellow fever, an infectious disease that had caused numerous deadly epidemics all over the world.

In 1934, at which point Brazil had managed to wipe out the mosquito in several cities in its northeast, the country launched efforts to do so nationwide. In 1942, it announced it had succeeded, through a combination of public education and fumigation. Five years later, a collection of South American countries met under the auspices of the Pan American Sanitary Organization to plan on wiping out Aedes aegypti across the continent.

It took 15 years, but by 1962, 18 countries plus several islands in the Caribbean announced they had eradicated the mosquito, thanks to hefty doses of the insecticide DDT, military-grade organization and plenty of funding to train personnel and buy equipment and supplies like DDT. In Brazil, the process involved 617 million house visits from 1931 to 1958.

It took far less time for the programs to eradicate Aedes aegypti to become victims of their own success. As these efforts succeeded, Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and the diseases they carried lost political importance, and attention to them diminished, as did funding.

From there, it did not take long for mosquito-borne diseases to surge again, according to Max Jacobo Moreno-Madriñán, an assistant professor of environmental health science at Indiana University-Purdue University in Indianapolis. He recalled an outbreak of dengue fever in his home country, Colombia, in 1978 that was so prevalent that it became part of popular culture; one song, “El Dengue de tu Amor,” or “The Dengue of Your Love,” listed symptoms of the fever. Today, dengue is estimated to infect 50 million people every year.

The broad success before and rapid unraveling of mosquito control programs after 1962 showed that beating the Aedes aegypti mosquito is not a one-time event, experts said.

“Vector control is really going to be only as good as what you’re doing at that time,” said Amesh Adalja, a senior associate at the Center for Health Security at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Baltimore. “As soon as you diminish those activities, you give the mosquito the chance to re-establish itself.” Even if a mosquito is declared eliminated from one region, it can be brought back in, thanks to trade and travel. “The world is a small place,” Adalja said.

As the world grapples with a growing number of cases of the Zika virus, which scientists strongly suspect, but have not proved, causes the birth defect microcephaly, public health officials are gearing up for the next round of man versus mosquito. Over the weekend, Brazil began a campaign involving 250,000 soldiers to distribute fliers urging locals to dump vessels containing standing water — not unlike the hundreds of millions of home visits made in the mid-20th century during Brazil’s first campaign against the bug.

Meanwhile, opposition to insecticides has softened somewhat among some in the U.S., said Conlon, of the American Mosquito Control Association, simply because of the unique fears that the Zika virus has wrought. The previous efforts took place during widespread and justified fears of the use of DDT, which was banned in the U.S. in 1972 because of its harmful effects on the environment and on people.

But if a 50-year-old lesson offers anything, initial efforts to eradicate mosquitoes are not all that matter. It’s what happens after they’ve been deemed eliminated that makes all the difference.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.