Hurricane Sandy Anniversary: Five Ambitious Plans For Protecting New York City From Future Superstorms And Climate Change

New York City has always been especially vulnerable to coastal flooding and storm surge, given its 520 miles of coastline and steadily rising sea levels. But it wasn't until Hurricane Sandy lashed the U.S. Northeast on Oct. 29, 2012, that the city was forced to start seriously considering plans to protect its people and buildings from future weather disasters.

Here's a look at five of the most ambitious proposals on the table today:

1. The “Big U” Protective System

The “Big U” project is one of a handful of plans to win the Rebuild by Design competition run by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development after Sandy. This curvy design envisions an eight-mile stretch of concrete, grass-topped protective barriers around the southern half of Manhattan. The 10-foot-high fortification would start at West 57th Street and run south along the Hudson River, before curling up around Battery Park and continuing up the East River to East 40th Street.

During storms, the berms would hold back powerful surges and dangerous floods. The rest of the time, they’d give New Yorkers an additional space to relax outdoors. In artist renderings, the protection system appears as a public gallery space, a pedestrian plaza and a tree-filled park overlooking the river.

The federal housing agency last year awarded New York City $335 million to begin implementing part of the design, which was developed by Bjarke Ingels Group, a Danish architecture firm. The first phase will run along the East River from 23rd Street to Montgomery Street and is expected to break ground in 2017.

2. Living Breakwaters

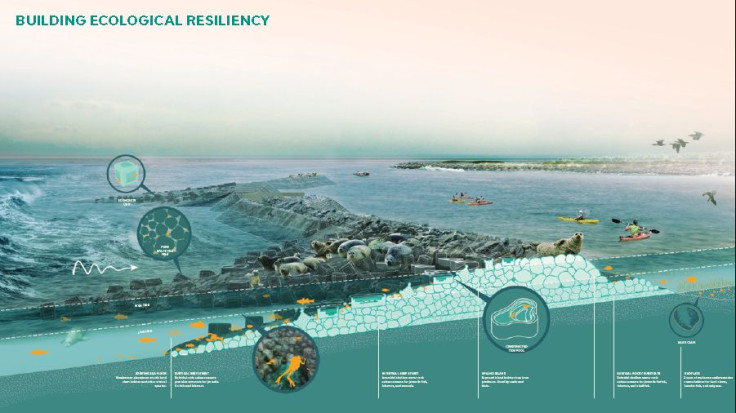

This design, also a Rebuild by Design winner, envisions building a “necklace” of breakwaters around Staten Island to absorb the strength of waves during storms and slow the speed of surging waters. The borough suffered some of the greatest losses to life and housing during Sandy, in large part because the island’s natural defenses against the seas, such as wetlands, have been paved over by development.

The Living Breakwaters project, designed by SCAPE / Landscape Architecture, would involve constructing clusters of concrete bricks off the South Shore that would also serve as small reefs for harbor shellfish, finfish and lobsters. Harbor seals and nesting birds could rest atop the exposed portions. Other structures dubbed “water hubs” would serve as classrooms, equipment storage or centers for data monitoring and emergency response.

New York received $60 million in federal funding to launch a pilot phase near the neighborhood of Tottenville. Kate Orff, a principal at SCAPE, said Staten Island could see living reefs within three to five years, local media reported.

3. New Aqueous City

Unlike the previous plans, this design would actually allow water to seep into New York, rather than block it out. New Aqueous City “blurs the boundaries between land and sea,” according to nARCHITECTS, the New York practice that presented the idea in 2010 at the Museum of Modern Art's Rising Currents project.

In the Sunset Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, a network of marshy hollows, drainage culverts and basins for capturing stormwater runoff would enable flood and river waters to infiltrate the area without inundating homes or overwhelming sewage systems. During dry periods, the system would function as a public park.

The plan would also extend the city out into the water. New Yorkers could develop housing and infrastructure across extensive piers, which would also serve to curb the power of storm surges. In the middle of the harbor, a network of verdant, man-made islands connected by inflatable storm barriers would also help weaken the waves. Biogas-powered ferries and an aerial tramway would enable people to move around the Waterworld-esque landscape.

4. A New Urban Ground

The New Urban Ground design would similarly let the water flow into Lower Manhattan, transforming the island into a kind of urban sponge. Mossy wetlands, sunken forests and tidal salt marshes would ring the island’s waterfront to soak up intruding sea water. Streets would be redesigned and repaved with more porous materials, allowing them to absorb stormwater and channel it out and down toward the perimeter wetlands, according to the plan, which was also part of MoMA's Rising Currents exhibition.

“We may not always be able to keep the water out, so we wanted to improve the edges and the streets of the city to deal with flooding in a more robust way,” architect Stephen Cassell, who conceived the plan with his firm Architecture Research Office and partner firm, dlandstudio, told the New York Times just days after Sandy.

5. New York-New Jersey Outer Harbor Gateway

This massive, $5.9 billion floodgate is the most conventional engineering proposal of the bunch. The barrier system would span the length of the New York Bight -- the shallow gap of water separating Long Island and New Jersey -- and form a link between the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens and Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

The Outer Harbor Gateway would have a series of five to 10 sliding sluice gates to control the flow of water into the bight. Container ships, tankers and large marine vessels could pass through a large opening in the middle, which would be closed by two saloon-style doors -- each the length of a football field -- during an extreme weather event, Metropolis magazine explained.

The British firm Halcrow, which is part of CH2m HILL, designed the project for a 2009 conference sponsored by the American Society of Engineers. Much of the gateway would be built by piling massive rocks into an upside-down V-shape -- a relatively low-tech approach that would be easy to adjust if sea levels rose above projected levels, the design firm told Metropolis. The gateway could realistically take at least two decades to complete.

Correction 11/3/14: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the SCAPE design firm won $60 million in federal funding for its Living Breakwaters project. New York State, not the firm, was the recipient.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.