Indonesia's Energy Subsidies Will Be Biggest Challenge For New Indonesian President Joko 'Jokowi' Widodo

Last week Indonesians chose their second popularly elected president, solidifying the nation’s transition into democracy 16 years after the Suharto regime ended amid massive social upheaval. Politically, they’re as distant as can be, but they have one important economic issue in common.

Joko Widodo, was a furniture exporter before he became mayor of Jakarta and later campaigned for a “people’s victory,” amid promises of a politically independent and economically sound Indonesia.

But it seems that one of these may be easier to achieve than the other.

“We’ve had positive developments from a democratic perspective, but the situation is volatile from an economic perspective,” said Michael Buehler, a lecturer at the Department of Politics and International Studies at University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

“But it’s going to be very difficult to make those economic changes,” he said, explaining the new, independent leader faces a parliament that probably won’t be on his side.

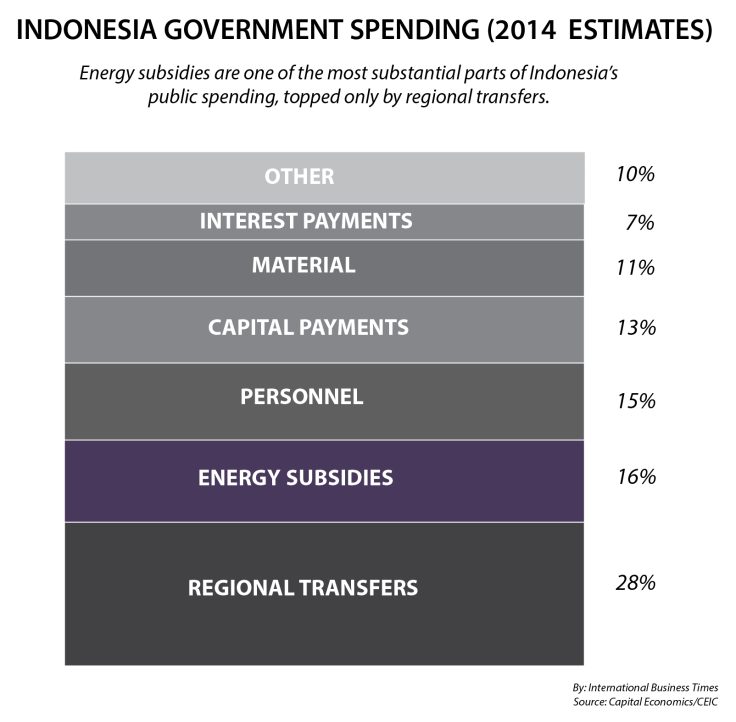

After years of growth cut short by the Asian Financial Crisis, Indonesia has been hugely dependent on public subsidies, especially on oil and gas. While it may have worked half a century ago, after the Asian Financial Crisis it became more and more expensive. Despite being the largest economy in South-East Asia, growth fell to 5.2 percent in the first quarter of this year, a four-year low as its budget deficit approaches 3 percent of economic output. Among the biggest issues are fuel subsidies, which now account for nearly 16 percent of government expenditure and rising.

“The budget is the biggest problem for Mr. Widodo and he will have to cut the fuel subsidy in his first 100 days,” said Raden Pardede, economic adviser to outgoing President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, The Financial Times reported. He warned that the next government will essentially be starting “broke, with no money to spend.”

The high subsidies put a major pressure on public finances and crowd out spending that could be put toward badly needed infrastructure updates and other measures.

Consequently, International organizations have urged Indonesia to increase fuel prices and spend more on infrastructure. It seems simple enough, but a divided parliament isn’t the only thing in Widodo’s way. In a country where more than 100 million people live on less than $2 a day, the decision to raise fuel prices has previously been met with protests, violence and even the end of a dictator in power for three decades.

“If there was one bold and timely policy to transform Indonesia, this is it,” wrote World Bank Indonesia economist Ndiame Diop in a March report, noting energy subsidies claimed more than a fifth of the government’s budget, more than three times what was allocated for infrastructure like roads, irrigation and electricity.

In theory it’s simple. The government will quit paying high fuel subsidies, and use the money to invest in infrastructure and development, to slowly balance the country’s deficit and set the economy back on track.

“In addition to crowding out high-priority spending, subsidies disproportionately benefit households at the top of the income distribution and throw sand on Indonesia’s remarkable record of prudent macroeconomic management,” he wrote. “Not to mention the fact that subsidies create disincentives for saving energy, developing alternative energy sources and reducing carbon dioxide emissions.”

However, subsidies in Indonesia, where more than half the population lives below the poverty line, are never that simple.

“Since the early days of its independence, subsidies have been a common feature in Indonesia’s economy,” wrote Christopher Beaton and Lucky Lontoh of the International Institute for Sustainable Development in a 2010 paper.

Subsidies have been a common feature of the Indonesian economy since its first Five Year Plan in 1956, created by its first president Kusno Sosrodihardjo Sukarno, to stimulate the private sector through public spending. By 1965, subsidies took up 20 percent of the state’s total revenue, and soon were used to support macroeconomic policies aimed at political stability with the help of loans from the IMF, World Bank, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and others.

But when the country was hit hard by financial crisis in 1997, then-president Suharto signed an agreement with the IMF for an emergency loan in exchange for certain reforms that included the cutting of basic commodity subsidies.

The price of kerosene was increased by 25 percent, diesel by 60 percent and gasoline by 71 percent.

“Although only one among a complex range of factors, the subsidy cuts were the trigger for protests over the next weeks from thousands of students in the cities of Medan, Bandung and Yogyakarta, which devolved into general rioting,” Beacon and Lontoh wrote.

Protesters destroyed and looted shops, set cars on fire and committed serious acts of violence. Theses protests added to growing political tensions that eventually led to the ouster of Suharto, who had been in power for more than three decades.

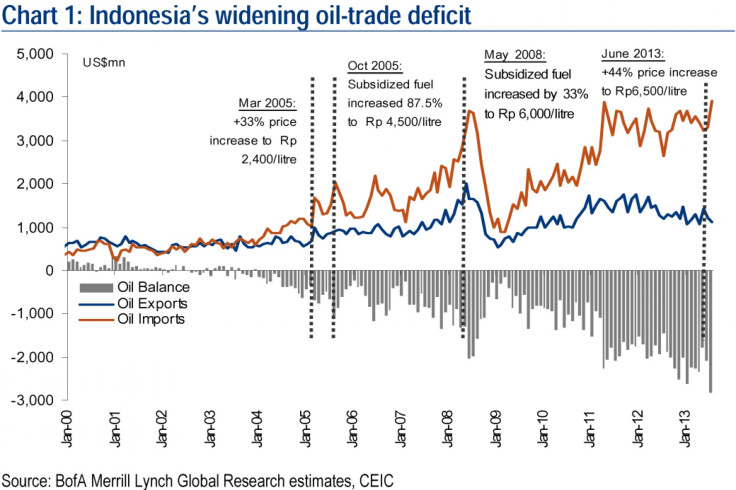

In March 2005, authorities placed 13,000 police officers on alert to deal with student protests in 10 cities after then president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono reduced subsidies and brought fuel prices up 29 percent, The New York Times reported. They tried again in October that year, raising the price by 87 percent to $1.71 per gallon, sending inflation soaring.

“I realize that this is not a popular policy … but we have to do it to save the nation’s budget and the future of the country,” Yudhoyono said, according to the Associated Press, adding, “Anarchy will only deter investment.”

By 2008 global oil prices topped $100 per barrel for the first time and the government predicted subsidies would increase nearly 40 percent on rising oil prices, and made yet another increase, according to the Jakarta Post.

Four years later, 80,000 Indonesians took part in violent protests when the government said it would raise fuel prices 33 percent after spending 15 percent of its budget on oil and gas subsidies the previous year amid soaring crude prices. Soon after, the government lowered its revised budget to prevent the hikes, the Christian Science monitor reported.

Economists expect the new president to make the changes, but gradually. “One of his most pressing tests will be reform of the country’s wasteful system of energy subsidies,” said Gareth Leather and Daniel Martin, economists at Capital Economics.

“Jokowi may tread carefully to avoid marring the early days of his presidency with mass protests,” they wrote in a note. If he can manage to gradually phase them out, it would also serve as a signal to investors that the country is making positive reforms. “It would give investors reason to believe that Jokowi’s presidency can deliver on some lofty expectations.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.