ISIS: The Islamic State and the Privatization of Terrorism

Not long after 9/11 it was decided a major part of the war on terror should address the financing of terrorist networks. The USA Patriot Act, for instance, was hurriedly enacted to prevent the illicit movement of funds across the global financial system. It's astonishing how outdated laws that oversee suspicious transactions within the banking system appear, in light of the recent high-profile activities of the group formerly known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS.

"The Patriot Act is completely outdated -- it is 13 years old, but even its updated version is for bankers at Lehman Brothers," said Loretta Napoleoni, an expert on terrorist financing, said. Western anti-terrorism strictures simply do not apply to ISIS, which is operating a closed, cash-only economy across territories it controls with well-organized armies -- a phenomenon Napoleoni has described as "the privatization of terrorism."

"The West is embarrassed at the failure to prevent this. So they say it has come from nowhere, in order to hide the failing of anti-terrorist measures, but these people have been operating for three years in Syria," she said.

Seed Funding

The group's earliest iteration was the jihadist operation established by Jordanian Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, sometime after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. Its rhetoric was similar to that of Al-Qaeda but its rather more convenient targets were Iraq's Shiite Muslims.

Al-Zarqawi was killed by a U.S. bomb in 2006. His successor, Iraq-born Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, waged a terrorist bombing campaign against the Shiite-led coalition government in Iraq. He later opened a second fighting front against Shiites in Syria and the Assad regime. The organization was in receipt of what could be called seed funding from backers in places like Kuwait and Saudi Arabia -- Sunni supporters who wanted to wage a war by proxy against the Assad regime in Syria.

"Most successful organizations have used sponsorship at the beginning to establish themselves. They then find a way to substitute their own operation," said Napoleoni. It's an approach that was used by the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] and Yasser Arafat, who received cash from the Arab League. Arafat used the capital to help establish business interests: legitimate ones such as textile manufacturing, and also criminal ones like drug smuggling.

However, ISIS is much more sophisticated than the PLO. It has been able to occupy strategic territories and has taken control of oil fields and dams. This means the group controls energy, which can be sold back to Assad regime, but can also be used to provide vital infrastructure for people living in the territory. In this way the militants can present themselves as a functioning state.

The individuals and organizations that originally backed Al-Baghdadi may have done so because they had concerns about Syria's connection to Iran. Syria allowed Iran to use some of its bases and was providing it access to the Mediterranean. But war waged by proxy isn't always monogamous and can become confused: Saudi individuals, who have sponsored ISIS in Syria, also backed Palestinians in Gaza. Meanwhile, backers and sponsors in Iran have backed Hezbollah. So you get an odd situation where factions that are waging war by proxy against one another in one territory, are actually fighting on the same side in another.

"If you are a smart and well-armed organization you can get money from a bunch of these guys," said Napoleoni. "I would say the initial amounts provided by backers were very little. This was between 2010 and 2011 -- there certainly would not be anything after 2012.

"This seed money would be cash and transferred by courier. It could also come in the form of training and weapons," she said.

A Real and Closed Economy

Before it gained power and supremacy the incipient Caliphate was a pretender among a number of rebel groups and tribal factions: ISIS used its sponsorship and backing to rise above the competition. It is interesting how the group has since allied itself with local tribes to conduct cash transactions, many of which take place at an individual level, carried out through small businesses. It is a real economy and a closed economy. This is how they control the financing of the infrastructure.

A Vice News documentary in Raqqa, Syria shows how far the Islamic State caliphate has progressed: there are propaganda vans; Shariah courts are resolving local disputes; the charitable ordinance of Zakat is being collected to help the poor. Sunni rebels have evolved by stealing and smuggling resources in war-torn Iraq, but only on a small scale, tapping into the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline running between Iraq and Turkey, for example.

Now the group has scaled up and taken control of entire oil fields, as well as a large chunk of Iraq's wheat and grain reserves, and has been selling these on through intermediaries and farmers. The robbery of the Iraqi Central Bank branch in Mosul is believed to have netted the group some 500 billion Iraqi dinar ($429m) in cash.

I would say $2bn to account for [Islamic State's] GDP is a bit low - I would say it's at least double that - Loretta Napoleoni

In Syria, ISIS reportedly confiscates property from Christians and Muslims with whom it does not agree, while in its northern Iraqi strongholds, it has collected taxes for more than a year. Its army collects military hardware wherever it goes.

It's not easy to estimate what the Islamic State is now worth. Back in the 1990s the CIA estimated the PLO to have a turnover of $8 billion to $12 billion.

"I would say $2 billion to account for [Islamic State's] GDP is a bit low. I'm just guessing, but I would say it's at least double that -- $4 billion to $5 billion," Napoleoni said. "Of course if you were to factor in the value of oil reserves it runs much higher."

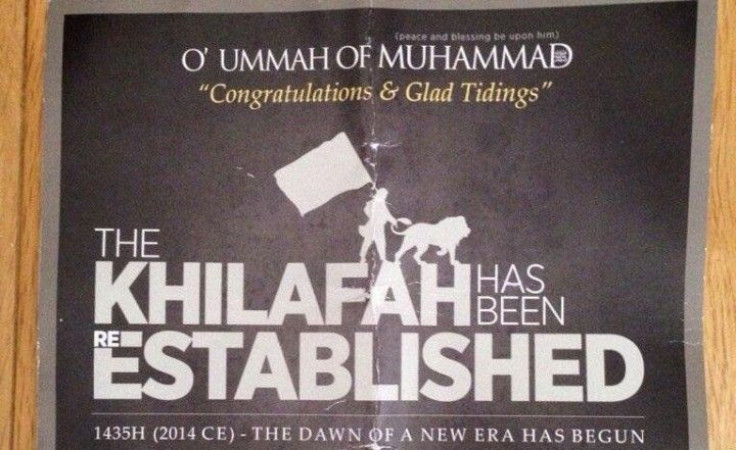

However, there is a sum much greater than the group's financial parts -- and that is its statehood. And according to religion, the caliph has the right to call jihad and in that case Muslims must go and fight.

"That's why people are flocking to the place. What would make professional people -- engineers, graduates -- drop everything and go and risk their lives?" Napoleoni asked. "What can be done to stop them? Only a war will do that now."

Loretta Napoleoni's forthcoming book The Islamic Phoenix is published in October.