Japan - Land Of The Rising, Or Falling, Yen?

Opinion

Leading up to the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ), two-day policy meeting in late January, many were wondering if the BoJ would allow Japan to become the “land of the rising yen.”

Foreign exchange traders and consumers alike have been guessing as to which direction the Japanese unit is headed and what the island nation’s strategy to win the silent global currency war is.

Currency wars produce no victors. As the Sunday Times’ columnist David Smith rightly pointed out, when growth is hard to come by, protectionism and currency manipulation come to the fore.

Many investors were expecting the BoJ to embark upon an aggressive policy designed to jump-start the flagging Japanese economy with more economic stimulus. The measures announced by BoJ Gov. Masaaki Shirakawa on Jan. 22 appear to have fallen short of market expectations.

The BoJ set a 2 percent inflation target, adding that it will shift to a U.S. Federal Reserve-style policy of open-ended asset purchases in 2014 -- its strongest commitment yet to ending deflation, despite disappointing investors with its timeline.

Fighting Deflationary Depression

The world’s third-largest economy has been in a deflationary depression for a couple of decades. That the yen, or JPY, has remained in a position of strength against the U.S. dollar, or USD, during that time is due to the country’s pro-export policy. This policy affects everything from cars to electronics, and it may be why investors view Japan as a safe haven during times of economic turmoil. The strong yet is also due the fact that past currency interventions aimed at diminishing the JPY’s strength -- such as the heralded Plaza Accord in 1985 -- failed to have a lasting impact.

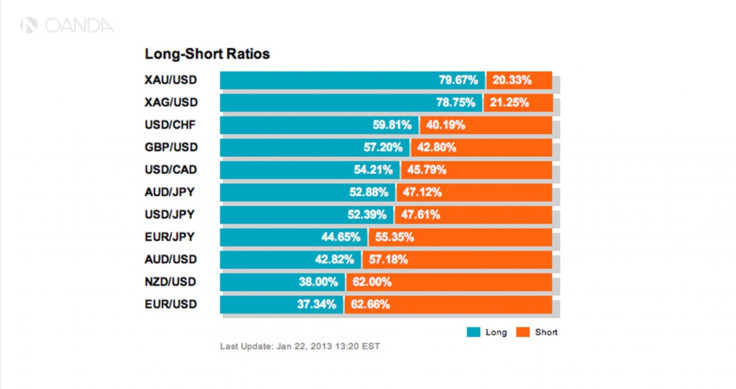

According to OANDA’s Open Position Ratios following the BoJ announcement, 52.39 percent of the market is long on the USD/JPY. This is reflective of the USD/JPY movement of the past three months, as the yen has depreciated by 15 percent against the greenback since last September, and by 25 percent against the euro since last August. The announcement, however, had many taking back their short-yen positions, booking profits, and allowing the yen to appreciate again.

Japan’s newly elected Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has been openly critical of the BoJ; he has threatened to rewrite the central bank’s mandate if it fails to make its monetary easing policies more agreeable. To that end, the prime minister triumphantly declared a “monetary regime change” at the conclusion of the BoJ’s two-day rendezvous, adding that a passageway has been opened “toward bold monetary easing.”

But one person’s poison is another’s food. Or, in this case, one country’s competitive advantage is another’s detriment. Everyone wants a weak currency these days, and with Japan going about intentionally weakening the JPY -- one of the world’s “big three” currencies -- it could generate repercussions.

The Desire To Be Weak

Interestingly, Akira Amari, Japan’s economy minister, remarked on Jan. 15 that if the yen grows too weak, import costs will jump and Japanese consumers would suffer as a result. His comments spurred the JPY to rise against the USD.

Amari subsequently clarified his comments two days later when he stated that the yen is still correcting from longer-term strength, in turn prompting its value to decline versus the greenback once more, pushing USD/JPY to record 2013 highs.

In Japan, the desire for a weaker yen has united business leaders and politicians since the 2008 credit crisis flattened the global economy. In 2012, the JPY hit an all-time high against the USD, which hurt major Japanese exporters like Sony, Canon and Toyota. A weaker yen will be welcome news to exporting companies after enduring a prolonged bout of "endaka," or a strong yen.

A strong JPY raises the price of Japanese exporters’ goods in the United States, making them less-competitive, and it erodes the value of their overseas earnings when repatriated into them yen. That said, it also increases Japanese firms’ purchasing power abroad to invest in new initiatives, such as a hiring blitz or acquiring new equipment.

Regardless, and as history has shown, there are no guarantees that the Abe government’s currency interventions will take root and produce the desired results over the long term. For export-sensitive Japan and its citizens, the plan had better work. General economic recovery is incredibly tough to come by nowadays, and a strong currency will only serve to undermine Japan’s fiscal health.

Dean Popplewell is the director of currency analysis and research at OANDA. Opinions are the author’s, and not necessarily that of OANDA Corporation or any of its affiliates, subsidiaries, officers or directors.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.