Jupiter’s Icy Moon Europa May Have Water Plumes, NASA's Galileo Data Shows

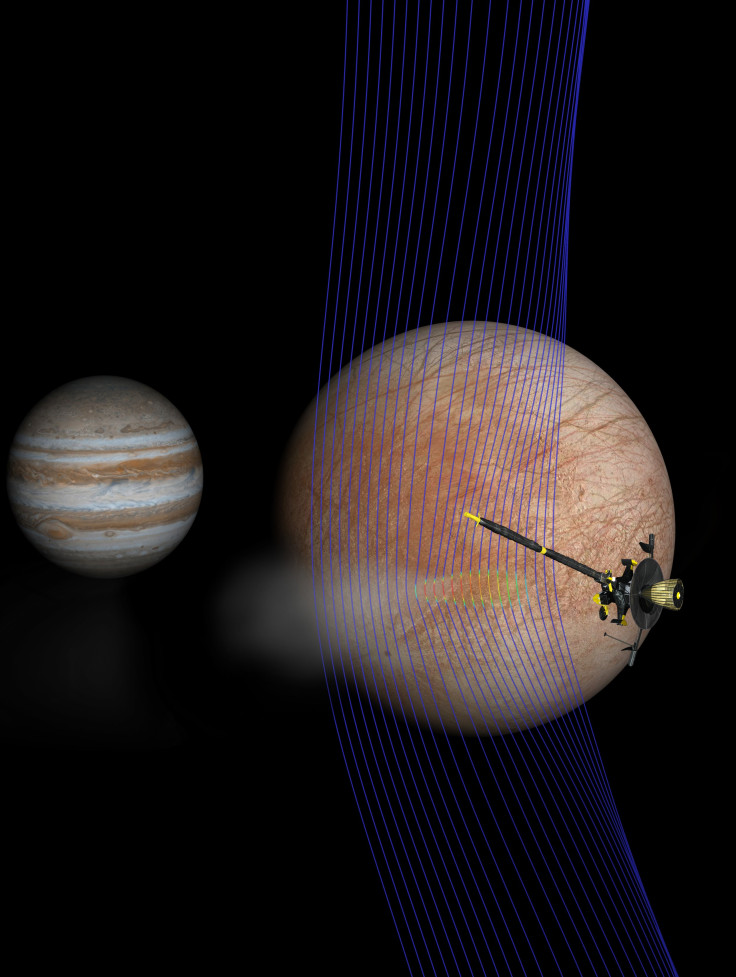

NASA’s famous Galileo spacecraft studied the environment around Jupiter and its moons between 1995 and 2003. The probe did a decent job in collecting and transmitting data for the space agency, but just recently, another look at that data, with latest modeling techniques, has hinted that the spacecraft might have detected a plume of water vapor during its close flyby of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa in 1997.

For years, scientists have considered the possibility of water, one of the most important ingredients to support microbial life, beneath the icy surface of Europa. Several images from the Hubble Space Telescope have also suggested that the moon might be venting out plumes, but the latest analysis of the data, which was collected up close on the icy moon, is probably the strongest evidence backing up the theory of subsurface water.

While the Galileo mission never focused on water plumes shooting from Europa, Xianzhe Jia, the lead researcher behind the study from the University of Michigan, thought that maybe the data collected by Hubble corroborated with that collected by the orbiter and could provide evidence of water plumes erupting from the moon.

“One of the locations she [the researcher announcing Hubble observations] mentioned rang a bell. Galileo actually did a flyby of that location, and it was the closest one we ever had. We realized we had to go back,” Jia, who is also the lead author of the study, said in a statement. “We needed to see whether there was anything in the data that could tell us whether or not there was a plume.”

So, they went through the data collected more than 20 years ago and got what they needed — a weird but quick spike in the magnetic field and a spike in the energy of particles in gases that had never been explained, Gizmodo reported. The finding led the team to believe that when the orbiter flew just 200 kilometers above the moon during the close flyby it was accidentally grazing through a plume erupting from it.

To delve into more into ejection of a plume from Europa. Jia and colleagues used sophisticated 3D modeling techniques developed by the university with magnetometry and charged particle signatures and dimensions of potential plumes captured in Hubble’s UV images. The simulated results displayed how the magnetic field interacted with a plume erupting from Europa and backed the observations noted in the Galileo data.

“The data were there, but we needed sophisticated modeling to make sense of the observation,” Jia said of the findings.

That said, the discovery could also play a critical part in supporting NASA’s Europa Clipper mission which will explore the possibility of life on the icy moon. In fact, according to NASA, if the plumes are indeed spewing from the moon, the orbiter might sample frozen liquid as well as dust particles.

“This result makes the plumes seem to be much more real and, for me, is a tipping point. These are no longer uncertain blips on a faraway image," Robert Pappalardo, Europa Clipper project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), said in the statement. “If plumes exist, and we can directly sample what’s coming from the interior of Europa, then we can more easily get at whether Europa has the ingredients for life. That’s what the mission is after. That’s the big picture.”

The study, titled "Evidence of a plume on Europa from Galileo magnetic and plasma wave signatures," was published May 14 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.