Long Ago, Earth May Have Had Two Moons [VIDEO]

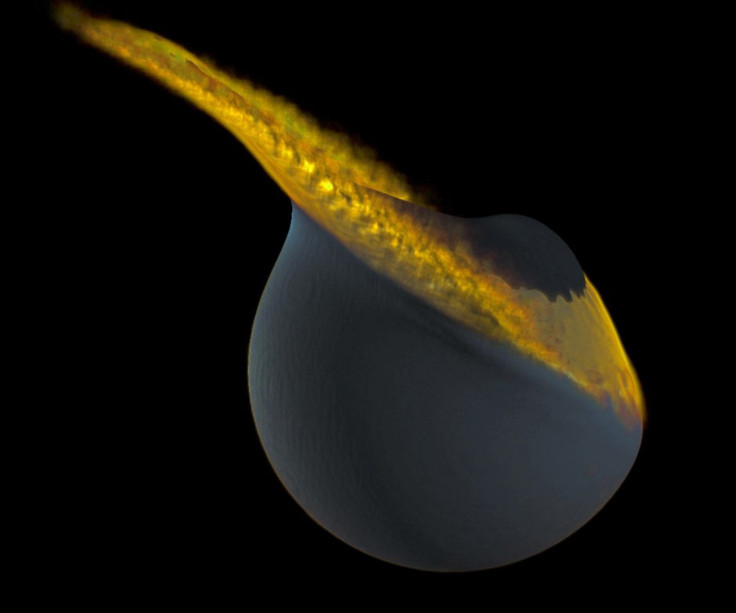

Once upon a time, a second moon orbited the Earth, but after a slow-motion collision with its bigger sister, our planet was left with one, scientists say. Astronomers believe that this collision, which lasted several hours, can explain the moon's symmetry.

The second moon around Earth would have been about 750 miles wide and could have formed from the same collision between the planet and a Mars-sized object.

A new report regarding the two moons was published in the Aug. 3 issue of the journal Nature.

The slow-motion collision explains a lot about the striking difference between the mountainous far side of the moon and the smoother lunar surface of vast plains visible to Earth in the night sky, said Erik Asphaug, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He co-authored the study with Martin Jutzi of the University of Berne.

Rather than form a giant crater, Reuters reported, a low-velocity collision like the one theorized in the study would have piled material up into a thick, jagged layer of solid crust. In fact, the moon's crust is about 30 miles (50 kilometers) thicker on its near side.

There is also a richer source of potassium (K) on the near side, as well as rare-earth elements (REE) and phosphorus (P), which are collectively known as KREEP.

Asphaug says this suggests that that something compressed the KREEP layer to one side of the moon, well after the rest of the crust had solidified. And he believes an impact is the most likely explanation.

"By definition, a big collision occurs only on one side," Asphaug told Nature, "and unless it globally melts the planet, it creates an asymmetry."

Jutzi, speaking to the UK Guardian, said the impact produced a disc of debris around the Earth and from this disc we got the moon, but there is no reason for why only moon would be formed.

Asphaug and Jutzi created a computer model showing that the collision a collision with a sister moon about one-thirtieth the moon's mass, or around 1,000 kilometers in diameter, can explain the current moon's state.

It is proposed that tidal forces from Earth would have caused both moons to migrate outward. The balance of forces became unstable as the two moons moved further away from the Earth and the two moons collided slowly, preventing a big crater from forming in the Earth's moon.

"It's not a typical cratering event, where you fire a 'bullet' and excavate a crater much larger than the bullet," Asphaug says in Nature. "Here, you make a crater only about one-fifth the volume of the impactor, and the impactor just kind of splats into the cavity."

Nature said Apshaug's theory isn't the only attempt to explain the lunar dichotomy, as others have invoked tidal effects from Earth's gravity, or convective forces from cooling rocks in the Moon's mantle.

"The fact that the nearside of the Moon looks so different to the far side has been a puzzle since the dawn of the space age, perhaps second only to the origin of the moon itself," Francis Nimmo, of the University of California, Santa Cruz, who proposed tidal forces as the cause. "One of the elegant aspects of [this] study is that it links these two puzzles together: perhaps the giant collision that formed the moon also spalled off some smaller bodies, one of which later fell back to the moon to cause the dichotomy that we see today."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.