The Machines Are About To Become Self-Aware And They May Not Like Us Very Much

"Open the pod bay doors please, Hal." "I'm sorry Dave, I'm afraid I can't do that." So said the sentient computer HAL at the controls of the Discovery One spacecraft to astronaut Dave Bowman in the 1968 Stanley Kubrick classic, "2001: A Space Oddyssey."

While computer-versus-human conflict has been foreseen in many films since then, a leading artificial intelligence researcher is now making the case that we need to start planning for the day that artificial intelligence combined with lethal capabilities will pose a real challenge to humanity.

Roman V. Yampolskiy, a respected artificial intelligence researcher and the director of the Cybersecurity Laboratory at the University of Louisville, is the author of a new study, “Taxonomy of Pathways to Dangerous AI,” due to be presented for the first time Saturday at the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence conference in Phoenix, Arizona. His paper is an attempt to spark a serious, intellectual discussion what controls humans can put on machines that don’t exist yet.

“In the next five to ten years we’re going to see a lot more intelligent non-human agents involved in serious incidents,” Yampolskiy said. “Science fiction is useful in showing you what is possible but it’s unlikely that any representations we’ve seen, whether it’s the Terminator or ‘Ex Machina,’ would be accurate. But something similar, when it comes to the possible damage they’d cause, could happen.”

Yampolskiy’s research sought to classify ways in which A.I. systems could be used to harm humans. The risk rises as people turn over more of their information, and their lives, over to computer software that’s so hard to understand. “Wall street trading, nuclear poiwer plants, social security compensations, credit histories and traffic lights are all software controlled and are only one serious design flaw away from creating disastrous consequences for millions of people.”

There’s no use worrying about a hypothetical Skynet, Yampolskiy says, because hackers are already designing autonomous code meant to create chaos. Ransomware, the method of cybercrime in which hackers take control of a victim’s computer and encrypt the data until the victim pays a fee, relies on automated attack commands (an automatic download, instantaneously locking a user out of his or her machine, for instance) that are, in essence, low level artificial intelligence. But top cybersecurity experts have failed to crack the encryption, and the FBI admitted in October the bureau often tells victims to “just pay the ransom” if they want their data back.

“Artificial intelligence is the future of cybersecurity, really,” Yampolskiy said. “We’re already starting to see more intelligent computer viruses capable of getting more personal information, capable of black mail, or holding your data hostage by encrypting it. This is fairly low-level intelligence, and really any type of crime can be automated.”

The Stuxnet virus, a product of the U.S. National Security Agency, sent shockwaves through the cybersecurity world when it was discovered in 2010. The virus, unlike criminal malware deployed before it, was completely autonomous once deployed, and eventually dug its way into Iranian uranium enrichment facilities that were not connected to the Internet via Siemens industrial control systems. Since then, researchers have noticed a trend of criminal malware being co-opted and made more intelligent by nation state groups.

“You can really compare it to biological science, like a virus,” said Kyle Wilhoit, a senior threat researcher at the cybersecurity company Trend Micro. “Once the malware is introduced to a host it can propagate to other hosts. Whenever I’m going about my research, that’s something we always take into account now: how would is possibly spread?”

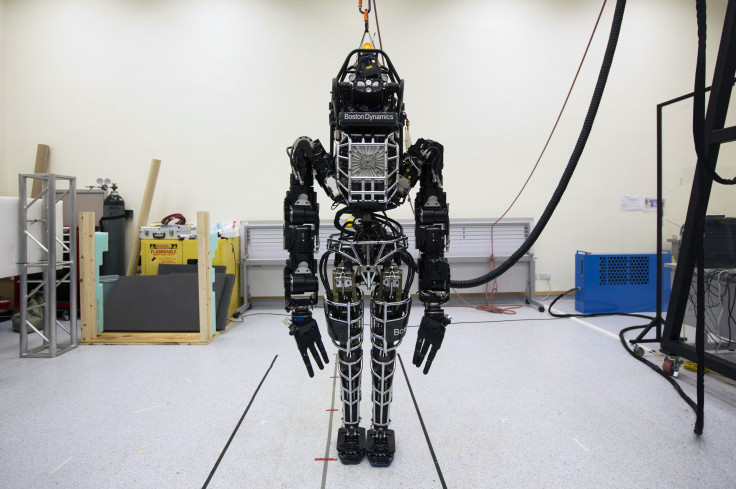

Another area of immediate concern for Yampolskiy is the artificial intelligence machines designed explicitly for combat purposes. Boston Dynamics, a Google-owned robotics company that receives funding from the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, is among the most visible companies developing military A.I. In 2013 the company unveiled Atlas, a humanoid robot capable of using a tool to break though concrete, connect a firehose to a standpipe and other emergency services.

One way to prepare for this kind of A.I. is a mandate that manufacturers include an off switch that can't be hacked on all machines, Yampolskiy said. Other groups including the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots have proposed a prohibition on the development and deployment of autonomous weapons altogether.

The U.S. government is listening. Director of National Intelligence James Clapper told a Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Tuesday “Implications of broader A.I. deployment include increased vulnerability to cyberattack, difficult in ascertaining attribution, facilitation of advances in foreign weapon and intelligence systems, the risk of accidents and related liability issues, and unemployment.”

Clapper’s remarks came after Microsoft founder Bill Gates, SpaceX and Tesla founder Elon Musk, theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and dozens of other experts co-signed an open letter calling for definitive research on how to create A.I. systems that will benefit, not damage, mankind’s survival.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.