March Madness 2015: Getting To The NCAA Finals Costs A Lot, But The Rewards For Most Are Slim

March Madness means many things to many people, but for almost everyone involved, it means money. Fans will bet some $9 billion on brackets and individual matches. The National Collegiate Athletic Association will rake in nearly $800 million in licensing deals. Coaches stand to make six-figure bonuses. Players, of course, will make zilch.

But for the colleges themselves, the math behind college athletics’ biggest tournament doesn’t always make sense. A wide gap separates the nation’s lucrative elite programs from the many that rely on universitywide budgets to stay afloat.

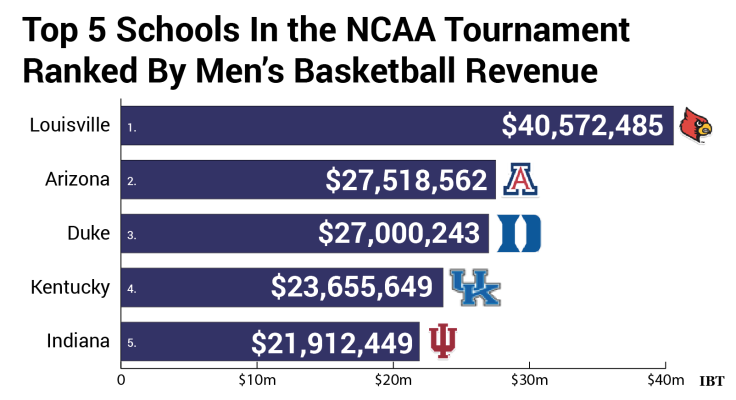

The marquee schools in college basketball earn multimillion-dollar windfalls for their athletic departments. Universities such as Louisville and Kansas boast huge contributor bases and ticket sales exceeding $10 million.

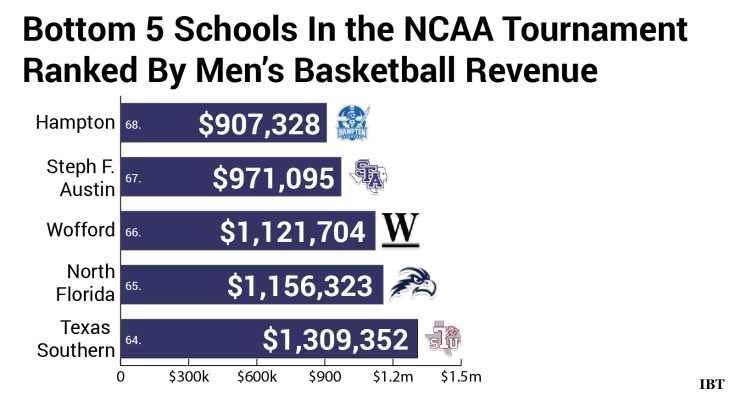

But most universities don’t enjoy such profitable programs. “For the overwhelming majority, the school’s central budget subsidizes” the basketball team, Andrew Zimbalist, who studies the economics of college athletics at Smith College, says.

As it stands, only a fraction of colleges make money on their athletics programs, according to Zimbalist. And the finances reported by individual schools may not capture the whole picture. NCAA guidelines leave wiggle room for reporting certain expenditures, but the cost to air-condition the gym or keep the stadium lights on might fall on the school.

Schools represented in the NCAA men’s basketball tournament tend to do a bit better, but as ESPN’s Darren Rovell highlighted, more than a third of the 68 teams just broke even or even lost money on their hoops programs last year. West Virginia University, for instance, spends $2.2 million more on its team than it earns, according to annual reports filed with the Department of Education.

While the cost of getting into March Madness may be steep, particularly for smaller schools, the rewards aren’t exactly colossal once they’re there. The NCAA will make upwards of $770 million on licensing fees for the tournament this year -- around 90 percent of its total revenue, most of which is distributed to colleges. But due to a complex funding system, programs that struggle to break even during the regular season won’t fare too much better in the tournament.

For each round of tournament play a team manages to reach until the championship game, the NCAA sends a “unit” to the school’s home conference. For the next six seasons, that unit earns the conference an amount that increases a couple percent each year, roughly $250,000 today.

But those winnings are generally split between all the colleges in the conference. A team that advances to the Final Four might bring in around $8 million over six years, but split between schools in the conference, the team will see less than $1 million of that.

“If we make a deep run in a tournament we’re not going to see that money until the next year or the year after,” says Rege Klitzke, the senior associate athletic director for business operations at Wichita State University, a No. 7 seed this year. Although the NCAA reimburses schools for some expenses, Klitzke says costs such as extra travel days and tickets for players' families do accumulate.

Still, the NCAA disbursements do end up balancing the costs of a manic tournament travel schedule. And athletics directors invariably point to the exposure that comes from competing in March. “I don’t think there are many schools that end up losing money on the tournament,” Zimbalist says.

Where does all this money go, then? According to Randy Grant, a collegiate athletics economist at Linfield College, two groups benefit most: the NCAA and its coaches. “A lot of the revenue actually goes toward the coaches’ salaries,” Grant says. “That’s the most expensive item in their budgets.”

Coaches and staff account for around 30 percent of Division I athletics expenditures. At top-tier schools, head coach salaries can reach well into the millions. Mike Krzyzewski of Duke University tops the compensation charts, with a reported salary of $9.7 million. According to data compiled by USA Today, 35 coaches in last year's tournament made seven-figure salaries before bonuses.

Once you add in bonuses, the tournament math becomes even madder. If Virginia nabs the championship, for instance, the school will pull in as much as $600,000 in NCAA allotments, along with its conference rivals. But the school’s head coach Tony Bennett would stand to make at least $800,000 on top of his $1.9 million base salary, easily exceeding the tournament winnings.

That leaves just one group conspicuously omitted. “Arguably, the ones who lose are the players,” Grant says. “They’re the ones who are doing the bulk of the work, and they’re not really being compensated.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.