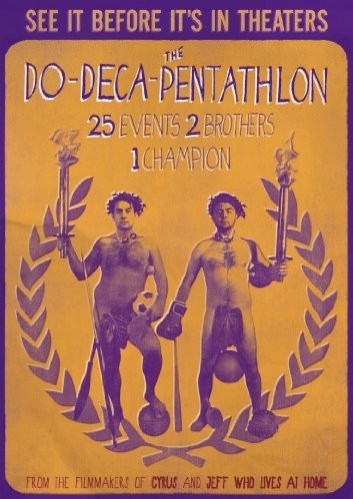

Mark And Jay Duplass Talk 'Do-Deca-Pentathlon,' Mumblecore And Their Working Relationship

One standout film at South By Southwest this year was undoubtedly The Do-Deca-Pentathlon. Written and directed by Jay and Mark Duplass, two notable bed head cinema figures, the uplifting indie is both hilarious and touching. It follows two brothers, Mark Kelly and Steve Zissis, who give in to nostalgic impulses by reenacting a childhood sporting completion.

Like their previous films, such as The Puffy Chair and Cyrus, Do-Decca is illustrative of the mumblecore movement, which began in the early 2000's when a string of new and exciting filmmakers began releasing low budget projects that were more evocative of real life than traditional cinema.

The International Business times had the chance to ask the Duplass brothers about their creative process, the mumblecore label, and whether or not a studio system rebellion is imminent.

Once the idea for The Do-Decca Pentathlon manifested, how did the story develop?

Mark Duplass: The script was written back in 2006. It was the first script that we started writing in the studio system. It was part of a blind deal that we had with a big studio. Then, through the process of writing it, we realized that it had the potential to be a big breakout sports comedy -- in that Will Ferrell type of way -- almost like Stepbrothers. But our hearts were telling us to make it small and have it have that scrappy, documentary approach to it. In that way, it would counterbalance the broad comedy style.

We traded scripts with the studio and gave them something different. After taking Do Decca back, we scrambled together some money that we earned as writers so that the film could be made.

This film, like so many of your projects, was part of the festival circuit. How do you think that events like Sundance have help shape the course of your career?

Jay Duplass: It kind of validated the way that Mark and I worked and have always worked. We're just two brothers in a cave trying to make a piece of art that doesn't suck. We're truly just trying to do work that we can be proud of. Once we started working that way and started mining the private conversations that we had about what we're obsessed with -- the movies did start getting into Sundance and the rest of the festival circuit. Eventually agents and studios started seeing it.

We had always been told that it's not a good idea to just go out to Los Angeles and try to make it. You want to be invited. That's what the festivals really provided for us -- a platform to show our films and eventually be invited to come out to L.A.

The film industry is immensely difficult to navigate, yet you've both managed to do so with respect and integrity. You've certainly retained your creative edge. How have you managed to make films the way you see fit?

M.D: Well, you can always be in charge of your art if you're making it cheaply, but having the stamp of approval from a festival like Sundance is very important for scrappy young filmmakers like us. Our first short at Sundance was a $3 film that we shot on our parent's video camera. It's hard to attract an audience to a project like that if you don't have that Sundance stamp. I think we owe a large degree of our success to festivals and to Sundance in particular. They really were the first ones to foster us.

What's your personal feeling on being grouped with the mumblecore movement?

J.D: At that time, we had just made a film called The Puffy Chair for $1,500 that got a write-up in the New York Times. That was thrilling, and I don't think the film would have been written about in that way if it hadn't been associated with a movement.

Unlike the Dogme 95 film movement [the rise of avant garde cinema led by auteurs like Lars Von Trier], which was a decidedly conscientious movement that had rules in place, the mumblecore thing was just something that the press ascribed to a few filmmakers who showed up at South By Southwest in 2005 with some similarly themed films. But we never really reference it. We think it feels a bit reductive and exclusive. It feels like we're a part of a club.

Our goal is to get our films to as many people as possible and create a universal experience through the specificity of how we see life.

The film industry seems to be taking fewer risks than ever before. Do you think that there will be an artistic rebellion in which artists -- such as yourselves -- will start to alter the studio system so that it's more accommodating to indie/art house fare?

M.D: I think some people think that way. Jay and I are conscious of the business model as it supports our creative model. A couple of things are happening; technology can come from a lower budget sphere, and therefore a lot of great films can be made with cheap equipment. That's going to remain healthy and improve over time. In terms of people being able to take a maverick, creative spirit into the studio world, the only way to do that -- in our opinion -- is to make movies modestly. Movies like Cyrus and Jeff Who Lives At Home would not have been green lit at these studios if we had asked for the standard budget.

The reason we get these movies made is because we deliver big movie stars but we make the films cheaply. If you have the support of a big star and you pull them in at the right price -- studios know they'll make their money back with the home video release. That's one way to get a riskier, bold piece of art made.

How does the creative process between the two of you typically begin?

J.D: It starts with Mark and I hanging out and talking about life and ourselves. We'll tell stories about things that we've done and said or things that have been said to us. Now it's branched out to our loved ones and people that we know. We sort of have this giant bowl of soup that we're constantly stirring up and talking about. Eventually, one idea will emerge and we'll say, 'Wow this has some traction.'

Do you think that the reason you both work so well together is because you're able to tell one another when something in a script or scene isn't working?

M.D: It defiantly can be. Jay and I are very close friends, but I think the key thing to remember is that we're not running an investment portfolio firm that feels stable to us. We're in a very precarious business that requires us to be on our feet and to have our arms lock together and use the forces of two heads to do well in the business. That prevents conflict in the working relationship. If you squabble with one another, you're going to f-k yourselves.

Is a lot of your working relationship grounded in honesty?

J.D: Oh God yes. It's beyond being able to 'tell each other' something. All we have to do is look at each other's faces and we know what the response is. That's something that is an enhancement of working as a team.

The movie making machine is such that people just want you to say, 'It's time to move on. We can move on.' We're able to put our hand up and say 'hold on a second. Was that truly great and inspired?' If not, we have to figure out what it's going to take to get there. In a high pressure situation of shooting, especially on a studio film where every minute, [there's] hundreds and hundreds of dollars [in] costs, it's a great help and comfort to have someone to share those ideas with.

The Do-Deca-Pentathlon is currently in theaters.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.